Unrest in Santiago last year, sparked by a proposed metro fare increase, led to constitutional changes for Chile. Photo by ausfilms/Shutterstock

They marched for human rights, for health care and education, but they came for the metro system, burning and damaging more than 86 stations across the city. Massive protests in Santiago last October forced the government to agree to rewrite Chile’s constitution, raise pensions, reshuffle leadership – and suspend a planned subway rate increase.

The connection between inequality and urban transport is not unique to Chile. In the United States, which accounts for more confirmed COVID-19 cases than any other country in the world as of this writing, reliance on public transport has been a kind of proxy for the unequal effects of the pandemic. Black households are more than three times more likely to have no access to a vehicle as white households. Transit systems have occasionally become ensnared in unrest too. After the murder of George Floyd ignited protests across the United States, metro services were suspended in multiple cities and at least one transit workers union encouraged its members not to aid in police crackdowns.

A growing divide between the haves and the have nots is among the many contributing factors to this global moment of reckoning for systematic marginalization of all kinds. Rural-urban divides are getting more attention for explaining political divisions in some countries, but intra-urban inequities remain a significant problem everywhere. These inequities within cities are growing especially fast in the global south.

On the periphery of growing cities, low-income families face long, costly and complicated commutes – and COVID-19 is making things worse, threatening a “great regression” in places like Colombia where entrenched inequities were beginning to erode. Some communities are essentially stranded in their immediate neighborhoods, which often lack critical services. But lack of access is not just a problem for low-income households. Low density suburban developments, frequently home to those with higher incomes, are often tenuously connected to the city by time-consuming, congested drives.

Transport that only works for some parts of the city is not only bad for individuals, leaving millions of those with modest means behind in ways that the coronavirus has made vividly clear, but it’s bad for the whole city. Estimates of the value of time lost in congestion range between 2-5% of GDP in Asia and up to 10% of GDP in cities like Beijing and São Paulo. Urban road accidents result in loss of productive years of life due to death and disability, cumulatively amounting to 2% of GDP in developing country cities.

A less equal city is a less productive, healthy and sustainable city overall, even if the costs take time to surface. We know that our transport systems and our urban planning practices (or lack thereof) contribute to large and growing urban inequities. But we also know how they can be part of the solution.

A Tale of Two Cities

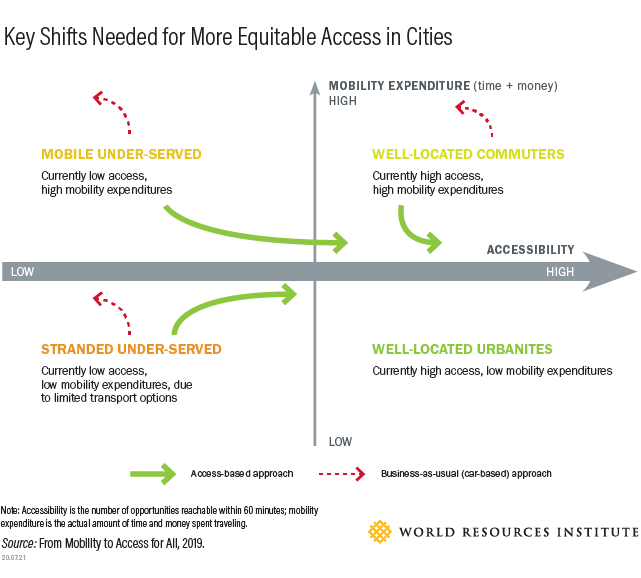

Each city has its own spatial and socio-economic dynamics, but the WRI study, From Mobility to Access for All, classifies some common patterns when it comes to access to opportunities. We created a framework that identifies four categories of people under-served by transport based on relative access and overall transport expenditure, including time and cost.

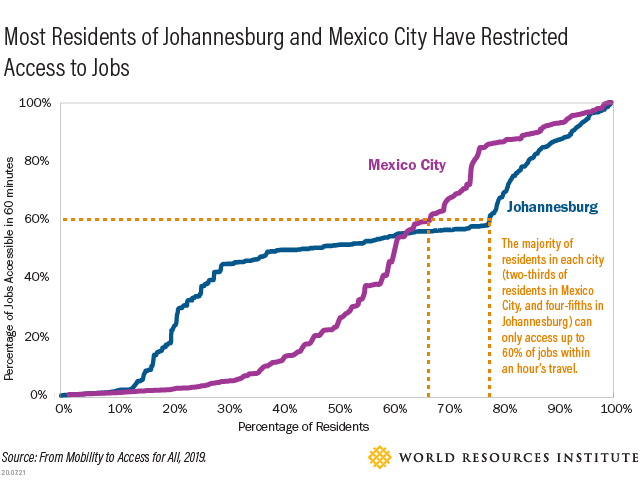

We gathered data in Mexico City and Johannesburg to explore this framework and understand who is under-served. These cities are typical of many relatively thriving global south cities where incomes have increased for many, but transport and land development patterns have been sub-optimal – they are both creating inefficiencies and widening inequalities.

Most people spend a long time commuting in each city, but the benefits of those commutes vary widely. In Johannesburg, just over 20% of inhabitants can access more than 60% of employment opportunities in the city within an hour of travel time. This population normally commutes by car or lives in more central locations. The rest of the residents, often living on the periphery and heavily reliant on walking and informal public transport, are excluded from a significant proportion of labor opportunities.

The Mexico City pattern is different. Even though a larger proportion of the population (33%) can access more than 60% of the jobs within one hour, thanks to a good combination of metro, bus rapid transit and semi-formal buses, the rest of the population is worse off. Even with a good network of public transit services, it is striking to see that a fifth of the city’s residents have near negligible access to jobs within an hour of travel. This reflects the fact that public transport is densest in the central areas of the city, while growing numbers of people are living in peripheral areas.

This clearly illustrates the need to ensure that land development decisions that determine job and housing locations across the city are supported by a high-quality public transport network, and that land and transport planning goes hand-in-hand.

In Johannesburg, only 9% of the residents can be classified as “well located,” with low transport costs and good access to jobs. In Mexico City the number is even lower at 7%. In other words, fewer than 1 in 10 people across both cities live in central locations or along public transit corridors where the majority of jobs are easily reached. Often, the two spatial factors overlap, as public transport is largely concentrated in central areas and these locations usually have higher land values that price out those with modest means.

Even though this analysis is very specific to the unique conditions of Johannesburg and Mexico City, one can expect similar results in other cities of the global south faced with both growing urban expansion and motorization. The majority of people in these cities face a higher than average cost burden to reach their destinations (74% in Johannesburg, 62% in Mexico City) and a significant proportion of residents are “stranded” without adequate access to opportunities and lacking the ability to spend more on transport (17% in Johannesburg, 31% in Mexico City).

Spatial Segregation as a Cause and Consequence of Inequity

When violent protests broke out in Santiago last fall, researcher Juanizio Correa from the Universidad de Las Américas, published a series of maps on Twitter reflecting a situation similar to Mexico City and Johannesburg. People in the urban periphery face very high travel costs (both in time and money) that limit their ability to take advantage of urban opportunities.

While a 4% metro fare hike was the initial spark, the protests in Chile were really the consequence of pressure that had been building for years, fed by profound socio-economic inequalities. While the international community regards Chile as a regional success story for its economic growth, this growth, as in other Latin American countries like Brazil, has been unequal. According to the OECD, Chile is the most unequal of all 36 member states.

Durante el último mes estuve trabajando en el #30daymapchallenge desarrollando una serie de mapas respecto a ciertas desigualdades socioterritoriales para #Santiago

Y tal como me comprometí, les comparto el resultado de los 30 días en esta carpetahttps://t.co/KwjaikJCba pic.twitter.com/lXh4VPJnjJ

— Juanizio Correa (@Juanizio_C) December 3, 2019

Juan Carlos Muñoz, who directs the Santiago-based Center for Sustainable Urban Development, writes that the way the city has developed, under an unfettered free market economy and privatization of key industries, has resulted in very good conditions for those that have more and worse conditions for those who have less. Those with higher incomes tend to have more transport choices and as a result better access: metro stations, public bicycles, bike lanes, underground expressways. These infrastructure elements are not present in lower income communities, which are also farthest from jobs.

The proposal to increase metro fares, then, hit the poorest hardest, threatening to restrict an already narrow pool of possibilities, and feeling to many like a strike at their last link to a better life.

Towards a More Equal City

Spatial segregation is a problem in cities everywhere, but there’s a unique opportunity to make a difference in many middle- and low-income countries now. More than 2.5 billion more people will be added to cities by 2050, mostly in relatively lower income cities in Africa and Asia. Because of the long life of physical infrastructure, planning and investment decisions made in these cities today will have impacts that echo for decades. If these places are to avoid widening spatial equity gaps, we need to do things differently.

Fortunately, the same transport-related approaches that help solve challenges affecting everyone, such as congestion, air pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, and traffic deaths and injuries, are the ones that can bring better access to opportunity for more people.

We need to design cities that offer resilient access to everyone over the long term, through complete and safe street networks, with adequate and safe space for walking and bicycling, and good infrastructure for public transport. New development must occur in already well-connected locations or in tandem with expanding access through street networks and public transport.

We need to advance multimodal public transport networks as the backbone of urban mobility, integrating walking and bicycling facilities, as well as existing informal and alternative mobility services that many marginalized populations rely on, into one interconnected system.

We need to consider targeted transport subsidies that can reduce cost burdens for vulnerable and marginalized populations. Bogotá has implemented targeted subsidies for low income populations since 2014, for example.

And we need to manage demand for travel in private motor vehicles, including cars and motorcycles, to reduce the social costs of these modes of travel.

These elements require good government institutions, courageous political leadership and sustained and creative funding. It is especially difficult to advance funding, which is why congestion and parking charges, as both ways to reduce negative impacts of private vehicle use and raise revenues for public transport, are so important. Indeed, evidence suggests that it is insufficient to provide higher quality walking, bicycling and public transport infrastructure alone to expand mobility options and access for all residents; car and motorcycle use needs to be controlled as well.

The unprecedented disruption of COVID-19, combined with popular movements against inequality and discrimination worldwide, may be the spark needed to jolt our institutions from complacency. We are seeing some examples of bold, creative thinking around transport from cities like Bogotá, Milan, Paris and London, as well as incredible moments of solidarity among urban residents even as anger over the status quo boils over.

But spatial segregation arises from both the location of jobs and housing and the mobility choices available to households. To combat these inequities before they erupt into unrest and even violence, it is not enough to provide new mass transit lines or change a policy here or there; we need to change the way cities are lived in, traveled in, and experienced by hundreds of millions of people every day.

Anjali Mahendra is Director of Research at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.

Dario Hidalgo is a Senior Mobility Researcher and supports WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities’ international team of transport engineers and planners from Bogotá.

Schuyler Null is Communications Manager for WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.