Since the mid-2010s, cities around the globe have witnessed the explosion of free-floating electric bikes, mopeds and scooters on their streets.

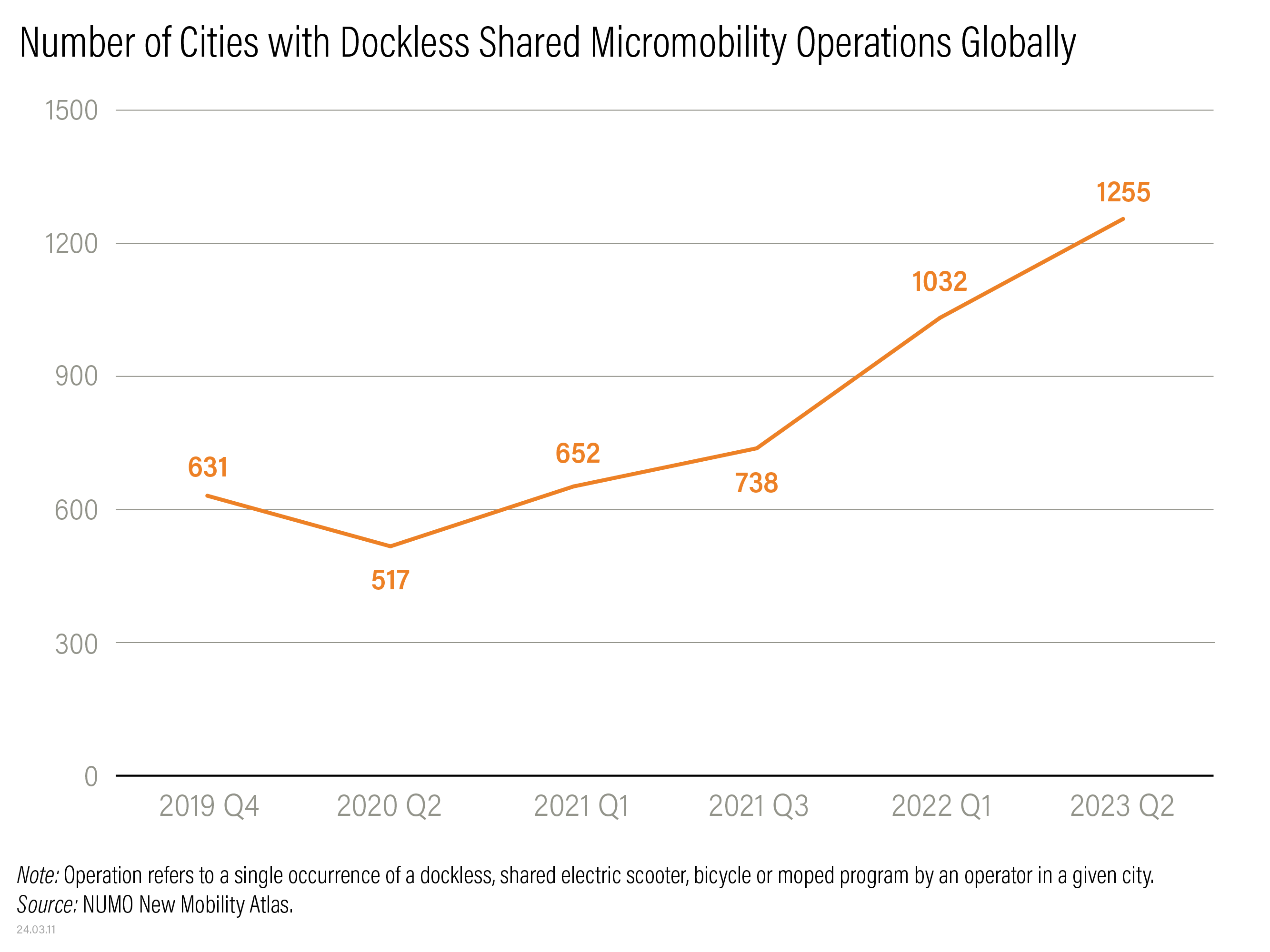

NUMO, the New Urban Mobility alliance, began tracking this phenomenon in 2019 with the New Mobility Atlas. Between 2019 and 2023, the number of cities with dockless, shared micromobility has doubled, with the number of operations having risen by 70%. While the industry witnessed a rapid decline in the immediate response to the COVID-19 pandemic, that downfall was short-lived, with operations soaring past pre-pandemic numbers by 2021.

Despite market volatility (since 2019, 94 companies have entered the scene, while 63 have gone out of business or removed all operations), the proliferation of micromobility shows no signs of slowing.

According to the latest update to the New Mobility Atlas in January 2024, since 2023, dockless micromobility can be found in 1,200 cities across 66 countries on every continent (except Antarctica) and is served by more than 150 unique operators (in this case, “operators” refers to a company that operates shared dockless vehicles, such as Lime or Tier). Since 2022, more than 200 new cities have introduced dockless micromobility and the number of dockless operations has jumped by more than 400.

Europe remains the leader in dockless operations and has seen the most expansion. NUMO’s analysis shows that since late 2019, Europe has accounted for at least 40% of all dockless micromobility operations globally, with the share currently sitting at three-quarters. Of the 48 countries in Europe, 38 have at least one free-floating micromobility operation and the top 10 cities worldwide by number of dockless operations are all located in Europe.

With this data in mind, we got curious. Why has dockless, shared micromobility flourished in Europe? We chose two cities in the top 10, as well as the country with the largest number of operations to look at what enabling factors allowed dockless micromobility to take off. As a bonus, we’re also diving into the city of Brussels, which has recently implemented stricter micromobility parking regulations.

Milan, Italy: Planning for Sustainable, Efficient Mobility

Milan has been high on the list since NUMO started tracking dockless micromobility with the New Mobility Atlas. Even the COVID-19 pandemic didn’t seriously affect the number of dockless operations. The city saw a large jump in operations between 2022 and 2023. The number of companies in Milan has also steadily increased since 2020, with a whopping 16 distinct operators as of June 2023.

The second largest city in Italy has demonstrated impressive dedication to multimodal transportation. In 2015, the city released its Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan, which expressly aims to shift citizens away from car ownership through such means as expanding the city’s cycling network from 9% to 25% of the urban road network.

The support for increased cycling infrastructure doesn’t stop there. While the pandemic caused many dockless micromobility operators around the world to reduce operations, Milan began its Strade Aperte (in English, “Open Streets”) initiative, which added 68 kilometers of protected bike lanes.

In 2021, the city approved Cambio (meaning “change” in English), a plan to bring 750 kilometers of protected bike lanes to the metropolitan area by 2035. These bike lanes will stretch from the rural outskirts to the city’s urban core. The plan aims to make cycling the most desirable option for getting around, which if achieved, would create one of the most comprehensive networks of protected bike lanes in Europe.

Barcelona, Spain: Supporting Shared, Active Mobility Through Urban Design and Infrastructure

A large coastal city, Barcelona is number four on our list of cities worldwide by number of dockless bike, moped or scooter operations. There are a total of 14 operations in the city, managed by 10 distinct operators. While these numbers are down since 2022, Barcelona shows no signs of reducing its commitment to active mobility.

Similar to Milan, Barcelona has also heavily invested in cycling infrastructure and design that discourages the use of cars. The city’s 2024 Plan de Movilidad Urbana (PMU) (in English, “Urban Mobility Plan”) puts forward more than 300 actions to reduce the percent of trips made by car to just 18%, while also encouraging trips made on foot and by public transportation and cycling. This plan is a renewed version of the PMU enacted in 2013 that transformed parts of the city into superillas, or superblocks, that prioritize public space for walking and biking by reducing space dedicated to cars.

Barcelona has also seen rapid growth in its bike lane network, which grew from just 10 kilometers in 1996 to 209 kilometers in 2019, half of which were installed after 2014. Like Milan, Barcelona acted during the pandemic to install 21 kilometers of pop-up bike lanes, which the city plans to keep. The city continues to construct new bike lanes and is redesigning roads to separate cyclists and drivers.

Germany: A Flexible Regulatory Environment for Cities to Boost Micromobility

As of June 2023, Germany has the most dockless micromobility operations out of any country, with 360 across 139 cities. This nation of around 83 million people has more operations than the United States, despite having a quarter of the population.

Germany has remained in the top three countries in each iteration of the New Mobility Atlas. While there was a sharp decrease in the number of distinct operators between 2022 and 2023, in part due to operators shutting down altogether, this has not stopped the massive growth of Germany’s dockless micromobility industry.

Since 2019, when electric scooters launched in the country, Germany has also experienced the greatest increase in the number of operations, which had more than doubled by 2023. This growth is entirely attributable to electric scooters, suggesting that these devices may have the lowest barriers to deployment out of the three vehicle types that the New Mobility Atlas tracks.

But electric scooters and other small electric vehicles haven’t always had the easiest time in Germany. They were officially welcomed when the Small Electric Vehicle Regulation (eKFV) was passed. eKFV, which is not a law and didn’t require parliamentary approval, gave German state-level governments authority over how they would regulate these vehicles, rather than the federal government deciding for the whole country. The reduced red tape to pass eKFV seems to have provided the flexibility that dockless micromobility operations needed to take off.

Following four years of rapid growth for dockless micromobility, Germany is primed to continue focusing on ways to make sustainable, electric and active mobility more convenient. The government released its National Cycling Plan 3.0 in 2023, which is aimed at promoting cycling nationwide. The plan consists of recommendations for state and local governments, as well as new government jobs dedicated specifically to the promotion of cycling. The plan also includes a rule requiring bike lanes to be included in all new or upgraded road construction.

Brussels, Belgium: Bumping Bike Infrastructure and Regulating Micromobility Fleets

Brussels, the capital and largest city in Belgium, was once a top city for dockless micromobility, with 13 operations and 12 distinct operators available in early 2022.

Beginning in July 2022, however, new rules around free-floating shared vehicles emerged in response to a rise in accidents involving dockless micromobility and concerns about parking that obstructed pedestrian zones. The minimum riding age was increased and micromobility vehicles were banned from operating on sidewalks. Additionally, scooters are now required to be parked in designated, marked spaces in certain areas of the city.

However, a strong regulatory environment is not new for Brussels and the number of dockless micromobility options in the city actually increased between 2022 and 2023. Beginning in 2019, operators were required to obtain a three-year license for free-floating micromobility vehicles. The city also set limits on the number of vehicles each fleet could operate to avoid overcrowding.

The rapid expansion of bike lanes is a possible reason as to why free-floating bikes, mopeds and scooters have thrived in Brussels. As of 2021, the city had 513 kilometers of bike lanes, around double the number of bike lanes in 2012. Additionally, philanthropy has stepped in to help the cause. The King Baudouin Foundation pledged 1.15 million euros in 2018 to help expand cycling infrastructure through the Bikes in Brussels Fund.

Increased cycling infrastructure has contributed to a culture shift. Brussels Bike Observatory measured an 11% increase in cycling traffic during rush hour between 2020 and 2021, meaning that the number of cyclists in the city 10 years ago has since tripled. Additionally, the share of miles traveled by car within the city fell from 64% to 50% between 2017 and 2021.

What’s Next for Dockless, Shared Micromobility?

As the micromobility industry continues to grow and shift, cities are thinking about how it can become a more established part of their multimodal transportation systems while also helping cities meet climate goals. Milan is gradually banning high-polluting vehicles from certain areas. By 2030, Barcelona wants to reduce single-occupancy vehicle travel by 20% and Brussels envisions 15% of all trips in the city to be made by cycling. Germany is aware that its traffic emissions need to be reduced by 42% by 2030 through a mixture of solutions that include electric mobility, cycling and public transit. Free-floating, shared mobility can play a part in meeting all these climate objectives and more.

However, for dockless micromobility to become a fixture of urban transportation that gets people where they need to go safely and efficiently, cities must allocate existing street space equitably and invest in infrastructure for walking, cycling and other forms of micromobility. Bike lanes, particularly segregated ones, are crucial for encouraging dockless as well as other micromobility modes.

Amid this growth and optimism however, the future of dockless micromobility is uncertain. In addition to Brussels, other cities have cracked down on free-floating vehicles on their streets. Washington, D.C., has implemented a fine for riders who don’t lock their vehicle to a public object. Lyft, which operates dockless scooters, will begin phasing in docks for their fleets. Paris, France, which had 18 operations by our count in 2019, has implemented a complete ban on dockless scooters.

But some cities are reversing previous bans and reintroducing dockless micromobility with new rules and infrastructure upgrades, likely because they recognize that these vehicles aren’t just a fun way to ride around the city. Many people, particularly low-income residents, rely on these services for necessary trips, like errands and commuting for work. That’s why it is essential to ensure that these services are safe, accessible and financially feasible, and that they aren’t encumbered by rules that make them too burdensome for riders to use.

As different regulatory approaches for dockless micromobility have emerged globally, cities will need to choose policies best suited to their specific contexts so that residents can still access these services safely and without obstruction to public spaces. According to the World Health Organization, over 1 million people die each year from road traffic incidents, with over 90% of these fatalities occurring in low- to middle-income countries. The process of integrating any active mobility options into a city’s transportation network should prioritize the safety of all road users and involve input from the communities that will benefit from these services.

Hosted by WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities, NUMO is an alliance organization that channels urban disruptions to build sustainable, just and joyful cities.

Lydia Freehafer is a Research Analyst for NUMO at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.