Contrasting high and low-income housing juxtaposed in Bloubosrand, Johannesburg, June 2016. Photo by Christina Culwick

While most cities around the world struggle with inequality, in Johannesburg, South Africa, the challenge is compounded by the legacy of apartheid.

In the apartheid era, black populations were relocated to the poorly serviced areas far away from job opportunities. Though apartheid officially ended in the 1990s, the legacy of segregation remains deeply embedded in Johannesburg; the city has been struggling to confront inequalities between its predominantly black, disadvantaged areas and its historically white, prosperous neighborhoods.

As described in a new case study of Johannesburg in the World Resources Report, “Towards a More Equal City,” Johannesburg is the first city in South Africa to try the innovative approach of “Transit-Oriented Development” to try and reverse the impacts of urban planning rooted in segregation.

A City Drawn Along Segregated Lines

After apartheid, the reformed national government focused on anti-apartheid planning efforts by expanding access to basic services. For 20 years, this meant funneling massive public investment into housing, water, sanitation, electricity and waste removal. But city officials left out an important component in their definition of “basic services:” transportation.

Consequences of this omission emerged over time. For example, in 1994, the national government launched the “million house program,” which provided fully subsidized housing and land to those below the poverty line. The problem was location. Subsidized units were built at the edge of the city; informal settlements, known as “townships,” received improved water and electricity services, but were disconnected from the city’s core, where jobs were located. Commutes were long, expensive and dangerous. Commuters spent more than 35 percent of their income on transport alone, sometimes traveling 4 hours with multiple minibus transfers to reach a job. With little pedestrian infrastructure, risks of accidents and road deaths remained high.

Introducing the “Corridors of Freedom”

Spatial isolation of the urban poor (and mismatch between housing and jobs) in cities is not unique to Johannesburg. Cities in Brazil, Mexico, Chile and Colombia face similar problems. To address this spatial mismatch between jobs and housing, is it better to bring jobs to people, or help people get to jobs more affordably and efficiently?

Johannesburg had disappointing outcomes when they focused on the former and hoped to overcome the spatial mismatch by focusing on mobility. Their long-standing service provision programs were to finally be bolstered with transit-related investments.

To guide these investments, the city turned towards a paradigm called Transit-Oriented Development, which focuses on creating compact, walkable, mixed-use, mixed-income communities centered around high-quality public transportation.

Bus Rapid Transit in Johannesburg. Photo by GCRO

In 2013, former Mayor Parks Tau founded Johannesburg’s flagship Transit-Oriented Development initiative, called the Corridors of Freedom. The project kicked off what would become a core tenet of Johannesburg’s strategic and spatial planning. Through the framework of Transit-Oriented Development, investments were to go to transit access and urban regeneration, public improvements that were historically neglected relative to other basic services.

The city’s new Bus Rapid Transit system, called Rea Vaya, now connects low- and high-income areas of the city. A handful of neighborhoods, deemed Corridors of Freedom “priority zones” because they connect the Central Business District to poorer districts and townships, have seen an increase of bike lanes and sidewalks, social facilities like libraries, community centers, clinics and parks, and mixed-income developments.

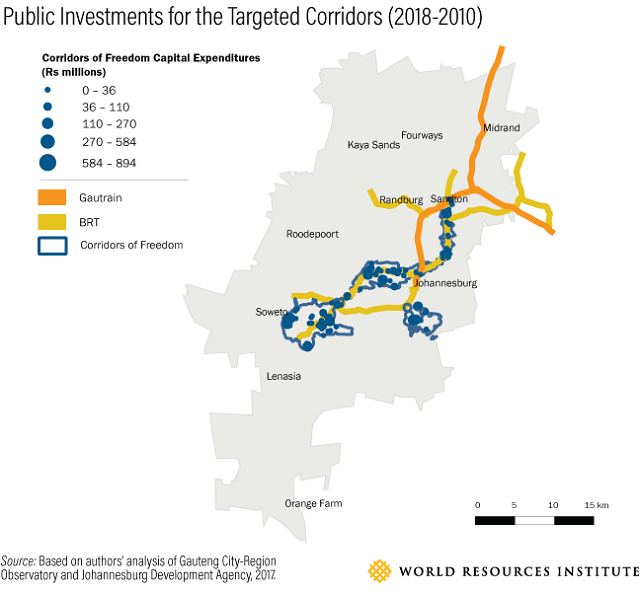

In Soweto, one of Johannesburg’s most well-known black townships with more than 1.3 million residents, a new pedestrian bridge helps commuters, largely low-income and informal workers, reach opportunities in the central district. The city invested more than $5 million in the Empire-Perth corridor, which connects Soweto and central Johannesburg, and constructed parks and other street infrastructure to encourage walking and cycling. Investments for public infrastructure and social facilities will continue across the city as part as the Corridors of Freedom initiative, as seen in the following map:

Another aim was to redevelop areas into denser, mixed-income, more affordable neighborhoods. Instead of affordable housing units on the edge of town, the city partnered with private developers to integrate affordable housing options into their redevelopment plans along the Corridors of Freedom.

Designed by Iyer Urban Studio, 2013, photo permissions from the city of Johannesburg.

By 2017, some areas saw successful redevelopment of neighborhoods with mixed-use, denser buildings for commercial amenities, student housing and middle-low income families. Private developers also committed to build 4,500 new affordable units along other routes of the Corridors of Freedom.

Redevelopment has not been without controversy and criticism. Wealthier neighborhoods in priority zones have complained about potential overcrowding and “undesirable changes.” The plan has also stirred debate over whether redevelopment benefits the most under-served populations. While some believe it is better to concentrate public investment in impoverished areas, advocates of the Corridors of Freedom caution against reinforcing the NIMBY (Not-in-My-Backyard) mindset and further isolating the urban poor in disconnected areas.

Lessons from Johannesburg

While faced with serious implementation challenges, the Corridors of Freedom initiative took root due to four factors:

- Political leadership and vision: Mayor Tau prioritized spatial inclusion. Though political leadership has changed, Transit Oriented Development remains an important part of Johannesburg’s long-term vision.

- Dedicated investment: The planning department controls Johannesburg’s capital budget. This is unique to South Africa, and helped prevent administrative backlog with budget allocations. This arrangement helped implement the TOD strategy quickly and effectively.

- Supportive and aligned national policy: In anticipation of the 2010 World Cup, the national government accelerated Bus Rapid Transit development as a priority. The first successful phase of Bus Rapid Transit paved the way for second and third phases.

- Private sector interest: In light of historical distrust between the city and the private sector, planners designed detailed precinct-level proposals for the Corridors of Freedom to ease the process for private sector investors. (This technical capacity in Johannesburg’s planning is noteworthy.) Examples of private sector interest include a niche group of developers willing to invest in affordable rental housing projects for young professionals.

For former Mayor Tau, the lasting success of this project was that “Transit-Oriented Development as a policy principle has remained part of the overall strategic planning framework of the city…ensuring that investments are going in infrastructure that was historically neglected.” The Corridors of Freedom were renamed the Transit-Oriented Development Corridors after a change of political leadership in 2016. Yet the project remains as an integral part of “Johannesburg 2040,” the city’s master plan for future development.

Cities considering Transit-Oriented Development – like Rio de Janeiro, Mexico City and Delhi – can learn a lot from Johannesburg. The city’s Transit-Oriented Development approach highlights coordination and collaboration with real estate developers within an overall strategy and vision created by the city. It also illustrates that jobs, housing and transport markets, informal and formal, are closely connected. Finally, it suggests that buy-in and longevity of long-term spatial transformation projects require collaboration between civil society, the public sector and private stakeholders.

Johannesburg’s Transit-Oriented Development approach is one small step towards tackling spatial inequalities. Though nascent, it has helped the city embark on an ambitious experiment for more inclusive urban growth.

A new case study in the World Resources Report, “Towards a More Equal City,” details Johannesburg’s experience with envisioning and implementing TOD. It describes the leadership, multi-level policy architecture, local level planning, and private sector incentives that enabled it. It also discusses how this experience is playing out today amid local political changes.

This blog was originally published on WRI’s Insights.

Jillian Du is a Research Assistant at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.

Valeria Gelman is a Communications Specialist and Program Coordinator II at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.