Germany has set an ambitious plan to make its streets friendlier and safer for pedestrians through strategic changes in land use, street infrastructure and other key areas. Photo by Eric Sehr/Flickr

Walking, as simple as it is, is key to many current urban issues. As car ownership grows, people are walking less and becoming less physically active generally, especially adolescents, more than 80% of whom are insufficiently active.

The impacts are manifold. Lack of physical activity is quickly becoming a major health risk, leading to 3.2 million premature deaths every year. The effects range from heart disease and obesity to depression and lack of social connection. More people commuting long distances in cars also worsens congestion, which can have staggering economic and air quality effects. Just two Brazilian cities lost $43 billion from traffic congestion in 2014, for example, and an estimated 4.2 million people die every year as a result of exposure to ambient air pollution.

Deliberate strategies to boost the safety, feasibility and allure of walking are needed if cities are going to accommodate the more than 2.5 billion additional urbanites expected by mid-century, while helping the world avert the worst effects of climate change. London’s Walking Action Plan, for example, aims to make walking the first choice of travel in the city for all short distances.

But Germany is dreaming even bigger. Following the blueprint laid out by their successful National Cycling Plan, Germany’s Federal Environment Agency and the German Institute for Urban Affairs launched a 55-page policy framework in October 2018 that lays the groundwork for a national walking plan.

Though the full policy is forthcoming, Germany’s framework plan recommends a series of clear national goals and strategies, and is an outstanding model for other countries to follow to develop their own plans to bring the change we need in cities.

Realistic Goals and Detailed Strategies

A comprehensive national policy can be an effective driver for large-scale change at the municipal level. Direction from the capital can encourage collaboration across different levels of government as well as across different agencies and departments.

Germany’s National Cycling Plan has proven effective in bringing together stakeholders from federal states, city governments and academia to implement the plan and make significant achievements, including a 12% increase in the number of bicycle trips, over 35% increase in kilometers cycled per day, and more than 30% reduction in cyclist fatalities since phase 1 of the plan was implemented.

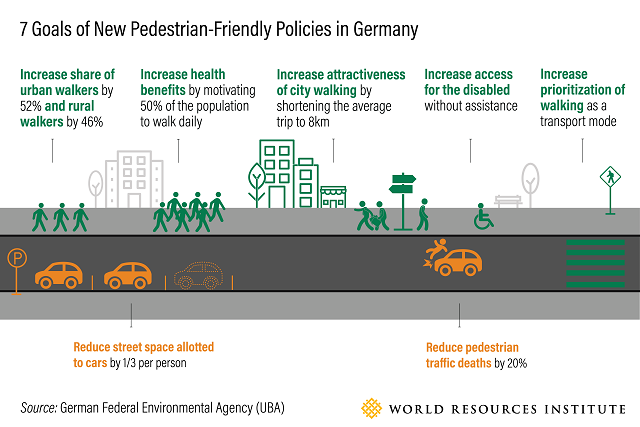

Germany’s walking policy framework proposes seven targets and five strategies to make streets friendlier to pedestrians. These address many of the systemic issues that have made today’s cities hostile to walkers, including safety problems (over 300,000 pedestrians killed every year, representing 23% of all road traffic deaths worldwide) and rising car ownership that is making cities more congested and less accessible to non-motorized road users.

A Safe System Approach

The goals and strategies proposed in the policy framework embody a “Safe System” approach to road safety. They are designed to improve the systemic issues affecting walking rather than focusing on user behavior as the problem. For example, one of the proposed national goals is increasing the share of people walking in Germany from 27% to 41% in urban areas while cutting the number of pedestrian traffic deaths 20% by 2030. In order to achieve this, the policy framework proposes introducing a 30-kilometer-per-hour standard speed limit in all urban areas and new minimum design standards for infrastructure elements, such as at least 2.5-meter-wide sidewalks, shorter and safer pedestrian crossings, better street lighting, and other measures that make walking safer. The idea is to change road systems, as well as road users.

Avoid, Shift, Improve

Germany’s goals and strategies apply critical components of the “Avoid, Shift, Improve” approach to planning, such as targeting changes in land use and urban form to shorten trips (avoid), disincentivizing the use of cars and encouraging more walking (shift).

The framework sets the goals of reducing car ownership to 150 cars per 1,000 inhabitants in all cities with over 100,000 inhabitants. It also proposes reducing the average parking space area per person from 4.5 square meters to 3 in urban areas.

The framework aims to achieve these ambitious objectives through promoting coordinated efforts between city planning and transport departments. Changes to land use and zoning criteria will encourage more accessible, compact, mixed-use developments, with restricted parking that incentivizes more walking and less driving.

—

There are many barriers to walking in cities today. Increased travel distances make it seem unfeasible; lack of connectivity means you can’t easily string together different modes of transport and destinations; more traffic crashes make it more dangerous; the romantic allure of the car is still alive and well, especially in fast-growing economies; and urban policies and investments often favor more affluent and politically powerful drivers over poorer pedestrians.

But many cities are recognizing the wisdom of a more active, multi-modal approach to mobility that can lead to major economic dividends, safer streets and more equitable cities. Low-carbon urban development could generate more than $24 trillion in value by 2050, according to research from the Coalition for Urban Transitions.

National governments have a critical role to play in supporting more walkable cities, and Germany’s policy framework is perhaps the most ambitious attempt yet to pull together the various land use, infrastructure, financial, legal and other instruments that national governments can bring to bear on the problem. Development of a strategic policy document based on this framework will soon start with a legislative process. Hopefully, the final policy will reflect the precedent set here, which is already a strong starting point for any national planning effort to get more people on their feet.

Claudia Adriazola-Steil is Deputy Director of Urban Mobility and Director of Health and Road Safety at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.

Alejandro Schwedhelm is Urban Mobility Associate at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.