This blog is also available in Spanish on IADB.org.

For most Latin American and Caribbean cities, public transport is the single most important way to access opportunity and essential services for most urban dwellers, from finding a job to education to health care. At the same time, it is “informal” or semiformal service providers rather than formal providers that account for more than half of all public transport trips in the region.

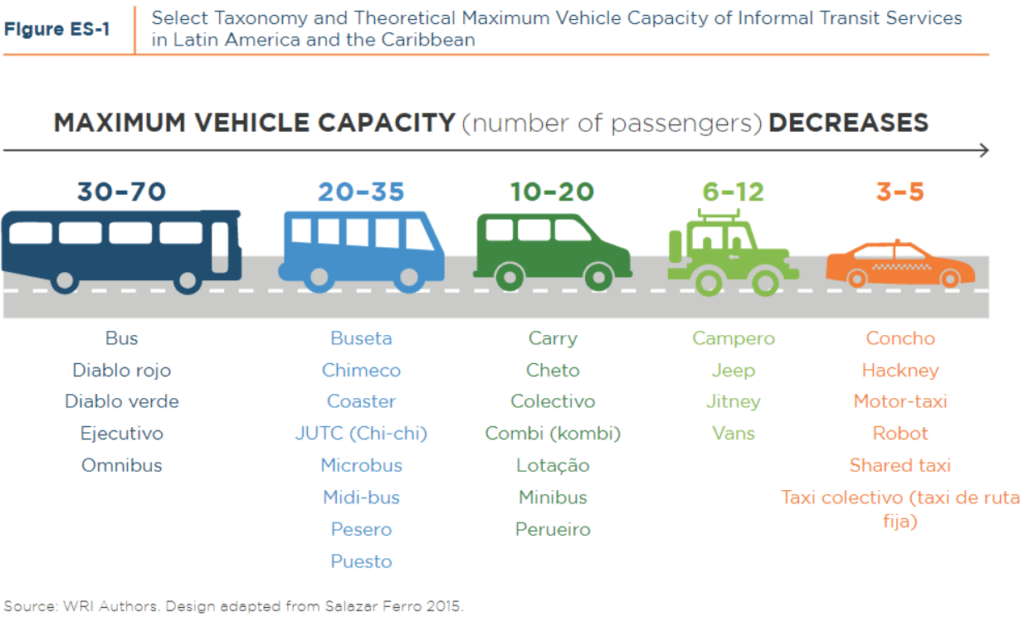

The term “informal” is problematic as it can marginalize the service, and in association, the users. Depending on the context and country, the term is synonymous with illegal – even though these services often fill market gaps resulting from limited government capacity. Indeed, across Latin America and the Caribbean, informal transport has flourished in many shapes and sizes, from the Diablo Rojo buses of Panama to the Lotação vans of Brazil.

How – and whether – to incorporate these services into formal public transport systems has been a longstanding policy question for municipal leaders and has resulted in differing approaches. A new publication from the Inter-American Development Bank and WRI Ross Center, with support from the Global Environmental Facility, analyzes the results of these reforms, especially efforts to bring informal bus providers into formal bus rapid transit (BRT) systems.

We find that “modernization” efforts by many cities in recent decades have produced mixed outcomes. Improving access for more residents means investing in informal transport services and integrating them with the formal when feasible.

The Role of Informal Transit

Informal and semiformal transport services offer very real advantages for some users, as their popularity and endurance show. Minibuses, taxis and other informal transport services tend to have ample coverage, particularly in peripheral areas of sprawling cities with large low-income populations. They provide high frequency of services and low fares. They also adapt rapidly to changing urban environments, often being the first to offer transport services to new neighborhoods or the only services available to informal settlements. Many passengers also appreciate direct, transfer-free services and relatively low walking distances from origin and to destination.

From local authorities’ perspectives, informal and semiformal services may be perceived as a problem to fix on the way to modernization, but they cover the mobility needs of most middle- and low-income populations with very low regulatory and supervision needs and without operational subsidies. They employ many people and generate entrepreneurship opportunities and social growth for drivers, vehicle owners and the businesses that manage them.

However, informal and semiformal services also have negative impacts on the environment, workers and some users. Due to lack of operational subsidies and the need to minimize costs to maintain profits, vehicles are not regularly replaced or adequately maintained, so many are unsafe and emit higher amounts of toxic tailpipe emissions.

Labor conditions can also be appalling, with long hours and no social security benefits for workers. For users, trips are usually slow, especially compared to BRT and metro systems that have dedicated rights of way. And as drivers compete for passengers on the street and vehicles are not necessarily roadworthy, these services cause congestion, and are often involved in deadly traffic crashes. During high occupancy times, travelers are often crammed into vehicles. Many users, especially women, can also be subject to abuse and unsafe travel conditions.

Though these challenges are not always unique to informal services (formal transit systems also face some of the same challenges in quality of service, crowding and more), to fully leverage informal transit as a legitimate option to improve the sustainability, safety and coverage of transport services in cities, they must be addressed.

The Challenges of Large-Scale Reform

Many Latin American cities have initiated transit reforms to “modernize” their informal systems, most often by introducing bus-based mass transit systems like BRT. The larger the scale of reform, the more time, financial capital, technical capabilities and human resources are required from the government. Our case studies show an emerging consensus among cities to assign planning, regulation and control to public agencies and operation and maintenance to the private sector. But they also show frequent underestimation by cities of the planning, funding and institutional capacity required for successful, equitable transition of informal services into a more formalized one.

Governments tend to believe that operational revenue will cover all necessary costs of such a transition. But large-scale reform requires sustained funding streams to keep new formal services running at a reasonable fare over the long term. This could include national funding, as in the case of direct grants or higher vehicle and fuel taxes earmarked for transit systems, or revenue from city governments such as economic demand management mechanisms (congestion charging) and land taxes (land value capture).

Santiago, Chile’s transition to the citywide Transantiago bus system shows an underestimation of planning needs and implementation risks that is typical. While Transantiago ultimately helped to achieve a more integrated public transport network, renew the bus fleet with lower-emission buses and reduce traffic crashes, the abrupt transition to a new system – including a lack of essential BRT components like off-board payment, passenger transfer facilities and median bus-lanes that could have improved quality of service – as well as unclear communication with the public contributed to a very strong negative public reaction. Transantiago continues to face low user ratings and high fare evasion, and was at the center of nationwide unrest last year. The brand is now being phased out with the introduction of low-emission and electric buses under a new name.

The amount of negotiation required to smoothly transition informal services as part of the government-led system may be the greatest and most underestimated challenge. Negotiating with incumbent informal and semiformal operators can be delicate and complex, and in some cases, governments may need to give them priority in the implementation of new systems or compensate them for abandoning their services.

In the case of SITP in Bogotá, Colombia, the city’s severance payments to incumbent operators were unusually high. The coverage and frequency of new services were then reduced compared to the semiformal services they replaced. The annual subsidy to cover the financial gap of formal operators exceeds $200 million per year. As a result, new services coexist with incumbents, reducing the potential revenue for both and creating further financial challenges for the city.

Alternative Approaches and Tech-Based Improvements

If cities lack adequate funding and institutional capacity for successful larger reform, smaller-scale improvements to informal and semiformal services should be considered. These can include business skills training, safety training for drivers, creation of transportation workers’ unions, bus fleet renewal and investments in operating environments of informal services – including bus stops, stations and non-motorized transport infrastructure.

Technology is also being leveraged in many cities for promising, scalable improvements, from apps allowing users to e-hail informal services to digitizing transport networks to better understand coverage and efficiency.

In Santiago, Dominican Republic, participatory digital mapping of semiformal services helped to improve user information. With transparency and visibility, mapping can be taken as the first step toward more inclusive service provision. Digital mapping efforts are also ongoing in many African cities, with similar goals to improve the quality of informal services and accessibility for residents.

Ultimately, integrated bus systems that have semiformal, informal and formal services working together, have the potential to better serve users’ needs and improve cities’ productivity, quality of life and sustainability through lower emissions, cleaner air and safer roads. Indeed, decarbonizing transport is critical to achieving global climate goals – and engaging with the informal sector is key to achieving a just transition.

But as our cases show, there is no single path to reforming informal and semiformal transport services. Advancing reform without strong financial and institutional backing may result in worse conditions than without the reform.

To evolve informal and semiformal operations into more sustainable, safe, high-quality services, cities must keep realistic expectations and consider a fair transition process, which means proactively involving informal operators and ensuring that their livelihoods – and the users who have depend on them – are not left behind. In the cases of limited options for large-scale reform, cities should prioritize investing in informal services and infrastructure to maintain access for underserved residents.

Dario Hidalgo is a Senior Mobility Consultant and supports WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities’ international team of transport engineers and planners from Bogotá.

Thet Hein Tun is a Transportation Research Analyst at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.

Lynn Scholl is a Senior Transport Specialist at the Inter-American Development Bank.

Claudio Alatorre is a Climate Change Lead Specialist at the Inter-American Development Bank.