“Climate change is affecting cities all around the world, and Freetown is no exception.” That’s what Eugenia Kargbo, Freetown’s Chief Heat Officer, told UrbanShift during the City Academy hosted in Kigali last year. Through her role—the first of its kind in any African city, and one of only eight worldwide—Kargbo is deeply familiar with the pressing need to address rising heat in Sierra Leone’s capital. “Over the past 15 to 20 years we have seen dramatic change in terms of weather patterns and…the risk that we face today,” Kargbo said.

Due to its equatorial location, Freetown endures consistent heat. On average, temperatures range from 24 to 32 degrees C (mid-70s to high 80s F), and frequently spike over 37 C (100 F). In 2020, there were around 30 days where the average temperature (overnights included) hovered around 81 degrees F. Without concerted effort, Freetown faces a future where by 2050, half the days of the year could see those sweltering temperatures.

The data is clear on how heat has intensified in Freetown over the last several decades. So is Kargbo’s memory. Growing up in Freetown she recalls a more temperate city surrounded by lush forests. As a child, she told The Guardian she enjoyed walking or cycling home from school in the afternoons. “But that has changed – the temperatures keep rising,” she said. “It’s very difficult to walk around the streets of Freetown in the afternoon hours. You feel very stressed.”

Global temperatures have risen consistently since the industrial era, and that increase has intensified in recent decades. Although Africa accounts for only 2-3% of global carbon emissions, according to the World Meteorological Organization, countries in North and Southern Africa face some of the most severe heat-related risks—and cities are especially vulnerable. According to its first-ever Climate Action Strategy, Freetown is at particularly high risk for heat stress compared to other parts of Sierra Leone due to the urban heat island effect, which has intensified due to deforestation, replacement of natural land with impervious surfaces (like buildings, roads and pavement), and emissions from industry and vehicles.

In Freetown, Kargbo said, residents are already feeling the effects of climate change, and data from Freetown’s Climate Action Strategy backs this up: 94% of Freetonians report feeling their city is hotter than it was five years ago, and 82% say they experience sensitivity to the extreme heat.

While extreme heat impacts all areas of society, from health to productivity, it’s particularly dangerous for young people, the elderly and people who work in exposed conditions, like farmers, market vendors and street traders. The 35% of residents—over 450,000 people—who live throughout the 74 informal settlements in the city’s hills and coastal areas are also vulnerable because their houses are made of sheet metal that trap already intense heat, and frequently lack cooling mechanisms.

Extreme heat in Freetown compounds and intensifies challenges related to climate change and development that the city is facing. “As climate-driven rural-urban migration continues, our forest-covered mountains are continuously decimated for new settlements, putting biodiversity at risk, reducing air quality and water availability, exacerbating the urban heat island effect, and just as importantly, limiting our tourism potential,” Freetown Mayor Yvonne Aki-Sawyerr wrote in her introductory letter to Freetown’s Climate Action Strategy.

But as evidenced by Freetown’s work on the Climate Action Strategy, which commits Freetown to becoming a net-zero city by 2050, and the appointment of leaders like Kargbo into innovative, forward-thinking positions like Chief Heat Officer, the city is taking steps to prepare for a more resilient future.

Through her role as Chief Heat Officer, which she’s held since 2021, Kargbo has already implemented several strategies to mitigate heat. In 15 of the city’s 42 markets that are open-air, Kargbo’s office has begun installing plexiglass canopies to shade vendors, many of whom are women, from the elements. She’s also overseen the installation of new public gardens to provide respite for residents, and continues to shepherd the “Freetown the Treetown” initiative, which was launched in 2019 with the goal of planting one million trees across the city by the end of 2022. While yet to hit its goal, the effort has already planted over 560,000 trees, provided over 550 short-term jobs for residents and raised awareness of the benefits of planting trees and protecting the environment. This tree-planting effort complement’s the city’s ambitious plan, laid out in the Climate Action Strategy, to build green corridors in its most vulnerable communities to improve biodiversity, provide shade, improve air quality and even help address food insecurity by planting fruit trees.

While much of Kargbo’s work involves taking concrete actions to mitigate the effects of climate change, she also sees raising awareness and inspiring community action as a significant part of her role. “When you talk about extreme heat, people will tell you, ‘oh yes, the weather is hot,’ but they’re not linking that to climate change,” Kargbo told UrbanShift. Through her work, Kargbo is improving Freetown’s climate data collection and how that information is shared with the public, with the aim of empowering residents to better understand the factors that impact their lives and how they can take action. “To have a chief heat officer—someone that will focus on risk and identify solutions in a community—is important,” Kargbo said. “But everyone is a chief heat officer. For me, climate change doesn’t know any boundary. We need to work together at the city level, at the national level, at the regional level and the global level—but also at the community level.”

—

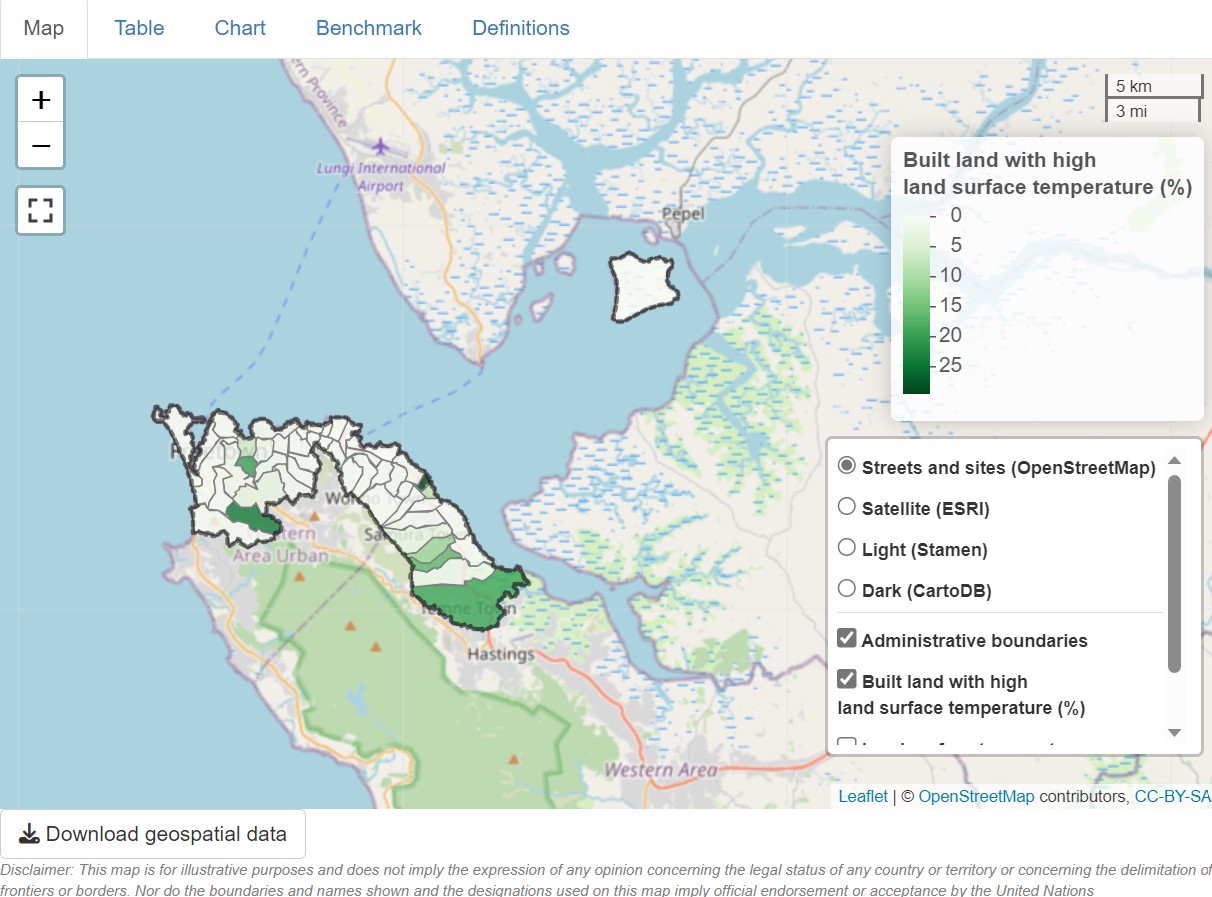

Many global initiatives are supporting cities worldwide to tackle heat related risks. UrbanShift helps to address technical and capacity gaps in cities in the global south by generating data on heat risks and helping cities to use that data to make informed, integrated urban development and planning decisions—which can help them prepare for risks, set goals and mitigate negative impacts. The UrbanShift and Cities4Forests Geospatial Data Dashboard is an open-source tool, available online for 23 UrbanShift and 12 Cities4Forests cities, and includes data and indicators on extreme heat.

According to data from the UrbanShift Geospatial Data Dashboard for Freetown, 99% of the city’s built areas have low surface reflectivity. Surfaces with low reflectivity absorb heat and transfer it to immediate surroundings, exacerbating the urban heat island effect. Areas with a high share of low surface reflectivity may be candidates for mitigating interventions, such as solar reflective roofs and pavements, or trees that can reduce the heat retained on surfaces or otherwise cool surrounding areas.

For a demonstration of how to use the dashboard, please reach out to urbanshift@shiftcities.org.

This article originally appeared on shiftcities.org.

Eillie Anzilotti is Communications Lead for UrbanShift.

John-Rob Pool is Manager of Knowledge and Partnerships for UrbanShift.

Jessy Appavoo is Head of UrbanShift & Regional Coordinator for Africa for C40 Cities.