The built environment is not on track globally to achieve its sectoral climate targets. Accounting for over a third of total energy system emissions already, the continued use of carbon-intensive materials paired with inefficient energy use throughout the built environment threatens to exacerbate rising emissions – especially as urbanization and cooling demands continue to escalate.

Current energy- and emission-intensive practices – including the production of building materials from hard-to-abate industrial sectors and the use of fossil fuels to power buildings’ heating, cooling and lighting – not only undermine national climate targets but contribute to air quality deterioration and skyrocketing energy costs. The built environment’s continued reliance on inefficient practices and non-renewable energy sources drives up greenhouse gas and fine particulate emissions. Vulnerable communities often bear the brunt of these negative side effects, as they cannot afford the increased cost of heating and cooling needed to withstand extreme temperatures and weather, nor the cost of healthcare to adequately mitigate the health impacts of consistent exposure to air pollution.

Countries around the world recognize the urgent need to undertake a global push for decarbonized and resilient buildings – and to act at pace and scale. The Buildings Breakthrough agenda launched at COP28 as a way for countries to join forces to meet emissions reduction goals within the built environment by 2030. Yet, advancing these goals requires concerted attention to address inequities and injustices. Historically, efforts to decarbonize the built environment have mainly focused on increasing energy efficiency and integrating renewable energy into existing buildings; rarely have they integrated equity, affordability, climate resilience or social justice considerations.

Putting people at the center of decarbonizing the built environment must be universally recognized and prioritized, especially when one in ten people who are exposed to unsafe air quality levels live in extreme poverty and one in seven (1.2 billion) lack adequate access to cooling solutions in their homes. Furthermore, the disparity in improvements to energy efficiency in affordable housing developments versus the rest of the buildings sector is growing as 2.8 billion people lack access to safe, resilient and affordable housing, with climate change progressively aggravating these conditions each year. The number of residents in underserved urban areas continues to increase, now reaching two in three in developing countries. And this division between better-served and underserved populations, known as the urban services divide, negatively impacts everyone in the built environment through lost productivity, higher costs, environmental degradation and an increase in negative health impacts.

A Sustainable Built Environment Mitigates Inequity

To avoid perpetuating such divisions, and to instead focus on advocating for and creating human-centered and sustainable built environments, it is necessary to prioritize developing, implementing and sustaining equitable and just decarbonization processes in the buildings sector. Because of its inherently complex and multifaceted nature, there are many interpretations of what constitutes a just transition in the sector, but several guides for this process exist – such as Embodying Justice in the Built Environment and Advancing Just Transitions in the Built Environment – which provide frameworks and examples of pathways to address these issues. These guides allow urban planners, resilience practitioners and policymakers to better assess climate vulnerability and injustices in the sector and apply these learnings in planning, designing and implementing interventions that promote resilience and justice.

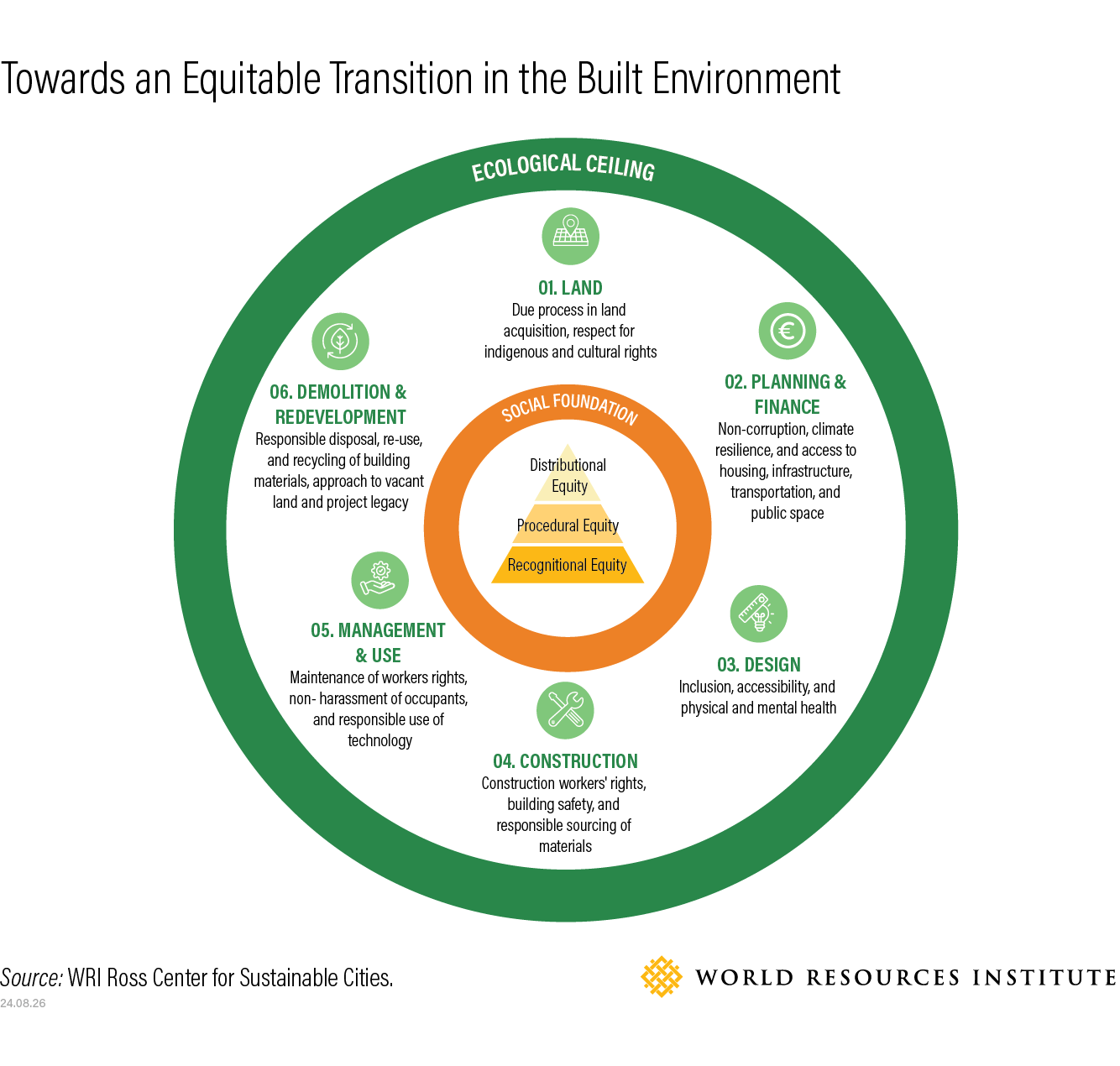

Similarly, to better plan for championing equity in the built environment, WRI’s visual representation, “Towards an Equitable Transition in the Built Environment” (pictured below), integrates three frameworks: the multiple dimensions of equity, the Doughnut for Urban Development and the Framework for Dignity in the Built Environment. This combined visualization emphasizes the balance between the social foundation and ecological ceiling across six key stages of buildings sector decarbonization: land acquisition, planning and finance, design, construction, management and use, and demolition and redevelopment. By incorporating principles of distributional, procedural and recognitional justice and equity, this model ensures that every phase of development addresses the rights and needs of all stakeholders, promoting an equity-focused, inclusive and sustainable built environment.

5 Actions To Achieve an Equitable Transition While Decarbonizing the Built Environment

WRI Ross Center experts recommend integrating five actions to achieve an equitable transition while decarbonizing the built environment. These actions are designed to guide stakeholders to create more equitable and sustainable sector- and city-wide plans, ensuring that new processes are inclusive, collaborative and effective in mitigating the impacts of climate change.

1) Include the Excluded

Understanding and accepting that decarbonizing the built environment is a complex problem that cannot be solved on its own is the first step toward effective collaboration. Ensuring all voices are heard helps identify the unique needs and challenges faced by different groups, promoting more inclusive and equitable outcomes. Collaboration must extend beyond initial conversations to include joint implementation and problem-solving.

Programs such as the Presidential Climate Commission (PCC) in South Africa exemplify this by overseeing and facilitating decarbonization actions with broad stakeholder engagement. The PCC’s inclusive process involves commissioners from government, businesses, labor unions, civil society and local leaders, ensuring that diverse perspectives shape the equitable transition process. Sharing lessons learned amongst the PCC’s members is crucial for scaling up successful practices and avoiding past mistakes. This participatory approach demonstrates that meaningful climate action can be achieved while promoting inclusive and equitable sustainable development.

2) Holistically and Systemically Align the Built Environment with Other Urban Sectors

Buildings do not exist in isolation; they are part of the larger urban system that includes transportation, energy and waste management, among others. Aligning buildings sector initiatives with other sectors can leverage synergies and mitigate unintended negative impacts.

For example, WRI’s Mapping Social Landscapes: A Guide to Identifying the Networks, Priorities, and Values of Restoration Actors can be used to lay out a more holistic view of environmental problems, identify and understand the interconnectedness and governance of various urban systems, and provide methodologies of social network analysis and values mapping, ensuring that buildings decarbonization initiatives, for instance, contribute positively to broader sustainability goals and do not inadvertently cause harm in other areas. This ensures a systems change approach of collaboration across sectors that prioritizes engagement with communities and acts as a catalyst to advance equitable processes in more purposeful, efficient and aligned ways.

3) Advance Multilevel Governance

WRI’s All in for a Net Zero Built Environment initiative brings together key global public and private sector partners towards accelerating the implementation of net-zero carbon and resilient buildings. It enhances cross-sector and multi-level coordination towards the transition to a decarbonized and more resilient built environment by growing local, national and international commitments to achieve net-zero carbon emissions for buildings by 2050. Implemented in Mexico and India, the initiative seeks to develop pathways to bring equity and climate resilience practices to more cities and equip decisionmakers with the insights needed to adapt to climate risks, achieve valuable co-benefits and scale up solutions in the sector.

Projects like this can successfully integrate and develop policies at the national level, as well as create city-level action plans that balance environmental concerns with the needs of the people benefiting from these policies. By identifying opportunities for capacity building and knowledge sharing to progress action on buildings sector targets and integrating social and environmental considerations, the initiative also aims to contribute to important co-benefits beyond the sector, including expanding access to energy, reducing household energy costs and creating green jobs. This comprehensive approach seeks to demonstrate that achieving meaningful climate action while promoting inclusive and equitable sustainable development is possible when specific actions and time-bound targets are embedded in policies, roadmaps and regulations across multiple levels of governance.

4) Integrate Mechanisms To Monitor and Report on Environmental Equity Needs and Outcomes

Establishing mechanisms for monitoring and reporting on equity outcomes in the built environment is critical for ensuring transparency and accountability to achieve long-term distributive equity. A longer-term perspective is essential, as short-term assessments may not capture the full range of impacts. As there may be unintended negative externalities or consequences in the project design or execution, such as projects aimed at urban revitalization can inadvertently lead to gentrification negatively impacting or displacing the very communities they intend to benefit. Periodic reviews over extended periods are necessary to evaluate true equity-oriented activities and outcomes and mitigate unintended consequences. As an example, the Built Environment and Health Equity report identified changes to the built environment that small- and medium-sized cities could implement to promote health equity by creating a framework for monitoring and reporting on equity outcomes, ensuring that health equity considerations are integrated into urban planning and development within the built environment.

5) Think Global, Act Local

This step involves recognizing global standards and goals, such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), while tailoring approaches to the local socio-economic and environmental context. Global frameworks provide a universal set of goals and benchmarks for sustainability and equity, but their implementation must be sensitive to the specific conditions and needs of local communities. For instance, the SDGs offer a comprehensive framework for addressing issues ranging from climate action (SDG 13) to reducing inequalities (SDG 10). However, applying these goals in a local context requires a nuanced understanding of local challenges and opportunities. Engaging local communities in the planning and implementation process ensures that solutions are relevant and effective to an equitable transition in any sector.

—

It is vital to recognize that the transition to a net-zero, equitable built environment is exactly that: a transition. It necessitates a systems approach and emphasizes setting, implementing and monitoring the appropriate processes and bringing a diverse group of stakeholders onboard, with the long-term objectives of creating an improved environment – built and ambient – for all.

Muhammad Ghiffari Aurelli was Regenerative Built Environment Intern at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.

Roxana Slavcheva is Global Lead for Built Environment at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.

Natalie Elwell is Director of Gender Equity Practice in WRI’s Equity, Poverty and Governance Center.