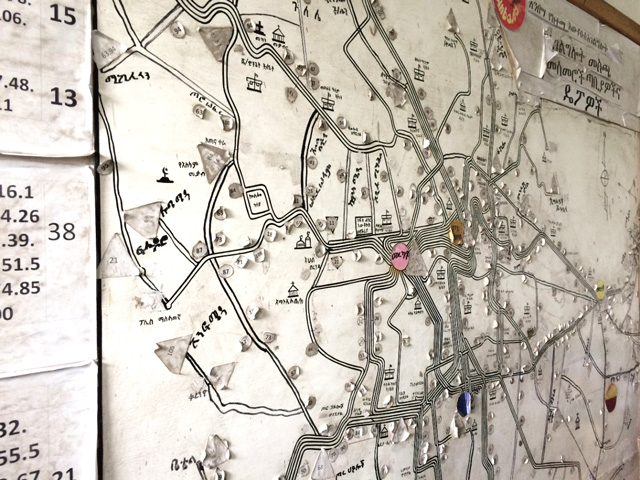

Addis Ababa’s public bus network is complex enough – but it’s missing the city’s extensive network of privately operated minibuses. Photo by Elleni Ashebir/WRI Africa

Hand-drawn in black marker and spanning an entire wall of Addis Ababa’s Anbessa company headquarters is a map depicting stops, timetables and fares for the city’s 73-year-old public bus system. Peeling icons and stickers tell a history of corrections and updates. The system is low-tech but far from simple, providing a remarkable snapshot of the capital’s spaghetti-like bus network.

Anbessa’s map, however, makes up only one piece of the Addis Ababa’s transit system. Missing are the trips of almost 11,000 privately owned minibuses that serve a large portion of the population.

In big African cities like Addis, Kampala, Abidjan, and Dakar, these “paratransit” services are responsible for the majority of public transport ridership, accounting for 70 to 100% of all transit rides. Paratransit owes its massive popularity to its flexibility, its middle-class affordability and its near-ubiquitous coverage.

Yet, despite this popularity, information on stop locations, frequencies and routes are at best estimated by riders and sometimes complete guesswork. This lack of information is a challenge not only for riders but for city planners looking to expand public transport that accommodates everyone.

The data necessary to include paratransit in formal planning is simply not there – yet.

Bridging the Divide Between Paratransit and Mass Transit

Although paratransit operators provide a much-needed service to riders at virtually no direct cost to the city, they also bring a host of challenges to African cities. Paratransit vehicles are a leading cause of pollution, they can be unpredictable in price and service, and are occasionally unsafe. As the region grows – and 90% of urban growth between now and 2050 will be concentrated in Africa and Asia – public authorities have announced intentions to reform, phase out, or flat-out ban paratransit in favor of more “modern,” high-capacity forms of public transit, like bus rapid transit (BRT).

But what if paratransit could be improved, rather than replaced? What if it complemented, rather than competed with other public transit?

There is a growing chorus of organizations in Nairobi, Gaborone, Accra and elsewhere that see a wave of technologies like GPS-enabled smartphones and open, crowdsourced databases as opportunities to bring innovative, data-driven solutions to improving paratransit. Through the power of data they hope to bring paratransit out of the shadows, upgrade mobility services, and combine the ingenuity of paratransit entrepreneurs with the volume of public mass transit.

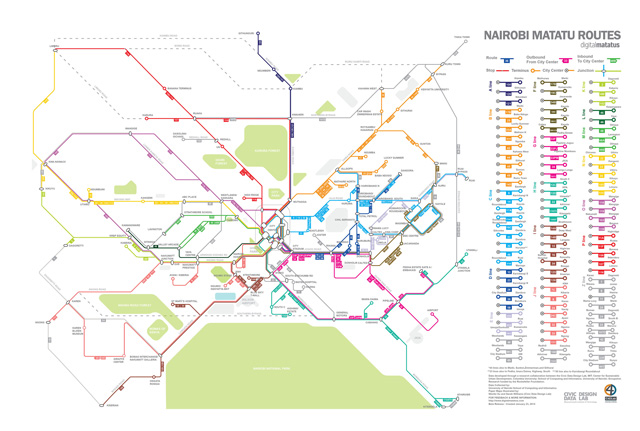

The routes of this movement can be traced to Nairobi in 2013. Digital Matatus, a team of researchers and students from MIT, Columbia University, and the University of Nairobi, set out to create a map of the capital’s matatu minibus network. Equipped with smartphones to collect GPS data, five students rode and mapped 135 major matatu routes. Digital Matatus cleaned and formatted the data to meet General Transit Feed Specification (GTFS), a data format originally developed by Google in 2006 that has since become the standard for recording and formatting complex transit data.

GTFS allowed Digital Matatus to make their data simple-to-use and easily shared. It allowed anyone to create maps, do analysis, or develop navigation and transit modeling applications. The biggest triumph came when Nairobi became the first and only sub-Saharan African city to have a paratransit routing feature in Google Maps.

Digital Matatus used GPS data collected by students with smartphone apps to create a London Underground-inspired map of Nairobi’s major paratransit routes. Map by Digital Matatus (click for full size and data)

Other students, entrepreneurs and city planners have since taken to the streets to map their public transport systems.

In Ghana, there is AccraMobility, where the city and French Development Agency (AFD) are working together to collect and use GTFS data to estimate passenger flows, optimize routes and track carbon emissions. In Egypt, Transport for Cairo, an effort driven by local entrepreneurs, is collecting and analyzing GTFS data to understand urban mobility needs in Greater Cairo’s rapidly developing desert towns.

GTFS data does more than make maps. Planners, researchers and civic hackers can use this data to measure progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals, which challenge cities to provide access to “safe, affordable, accessible and sustainable transport systems for all.” Data on access to transit stops and job opportunities, planning integrated systems, measuring ridership and service levels, redesigning and optimizing routes – these are all ways that cities can go closer to the SDG target.

Using GTFS data from Digital Matatus, we can see that access to jobs in Kibera, Nairobi’s largest slum, increases significantly as you combine different transit modes, like cycling and motorcycle taxis. Graphic by Travis Fried/WRI

An Open Digital Transport Resource Center

The burgeoning digital mapping scene bodes well for Africa’s intrinsically complex and decentralized paratransit networks. To help encourage this effort and make it easier to locate existing data, WRI Ross Center and AFD launched DigitalTransport4Africa.org in 2018.

To date, only a handful of African cities have mapped their public transport and even fewer have made their data open. DigitalTransport4Africa documents existing mapping efforts and provides resources for cities and universities looking to jump-start new projects.

Addis Ababa will soon join the ranks of African cities that have successfully mapped their public transport networks. Addis is unique in Africa in that it has multiple public transport options beyond paratransit, including the Anbessa Bus Company, Sheger Express Buses, a $475-million light rail network (the first of its kind in sub-Saharan Africa) and ongoing plans to construct a 17-kilometer BRT corridor in the next two years, in addition to as many as 14 more BRT corridors further in the future.

Given the mix of modes, open data and integrated transit planning is essential for Addis’ urban ambitions. WRI is working with the Addis Ababa Transport Authority and Addis Ababa University to digitize these networks and take one step closer to this goal. GTFS data on all four public transport networks – paratransit, buses, light rail and BRT – will soon be made openly available on DigitalTransport4Africa.

Smarter mobility planning goes beyond transit data. To meet the rapidly increasing mobility needs of Africa’s cities, cities must not only find more ways to integrate existing paratransit systems, they must also better understand the millions of passengers that rely on these services every day. Addis will use the new data to improve accessibility in areas where coverage is poor across all modes, not only improving mobility in the city but beginning to address inequality too.

Travis Fried is a Research Analyst with the Urban Mobility team at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.

Iman Abubaker is a Health and Road Safety Project Coordinator for WRI Africa Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.