Since its beginning in Sweden in the 1990s, Vision Zero has become a global movement to prevent road fatalities and serious injuries by undertaking a Safe System approach to road safety. But despite the documented successes of the approach in reducing injuries and deaths, many of the world’s roads have continued to get more dangerous, year after year. Why? More vehicles on streets and more people in cities are big components, but there’s also a frustrating gap between public commitment to Vision Zero and actions to make that commitment a reality.

In January 2020, we launched the Vision Zero Challenge with 24 cities in Latin America and the Caribbean to support a full realization of Vision Zero by identifying and surmounting barriers to change. The framework of the Challenge is based on knowledge exchange between experts and city leaders as well as between cities themselves. Through virtual trainings, participating cities have identified the barriers they face to implementing Vision Zero and learned methods for overcoming them.

More Than Just Traffic Crashes

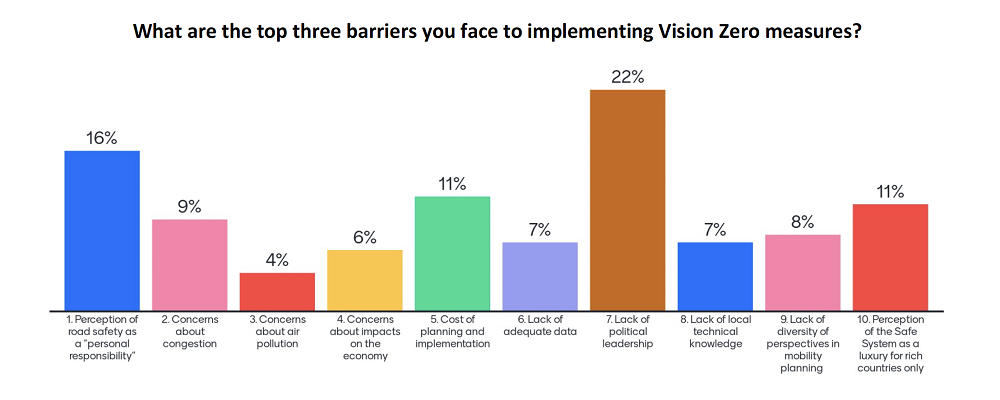

At the start of the Challenge, cities were asked to identify their top three obstacles to implementing a Vision Zero road safety plan. The greatest barrier identified was lack of political leadership. As Sergio Martinez from the District Mobility Agency in Bogotá said in one webinar, “Political leadership is the most important factor, at least to start the [Vision Zero] process.”

To help build momentum, experts pointed to the impact that road safety has on other important urban agendas, such as sustainability and public health, that commonly enjoy widespread political support. The policies and infrastructure changes that arise out of implementing Vision Zero not only reduce fatalities and serious injuries but also encourage sustainable, active transport modes by improving conditions for cyclists and pedestrians. As roads become safer for these more vulnerable users, people are more likely to choose walking and cycling over motorized transport, which can reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

According to Stuart Reid, director of Vision Zero at Transport for London, road safety and sustainability are necessarily interlinked. He explained that for London, which is working to increase active mobility, “fear and perceptions of safety were a major barrier to unlocking the potential for sustainable and active travel.” London’s Vision Zero Action Plan targets the dangers that produce these fears by lowering vehicle speeds and implementing interventions like the Safe Junctions Program that aim to improve facilities for walking and cycling at the most dangerous hotspots.

Increasing active travel also holds potential for improving public health and reducing the costs of traffic crashes. Each year, more than 100,000 people die across Latin America as a result of traffic crashes, representing an enormous social and economic loss. Data suggests that 1.5-2.9% of national GDP is lost due to traffic deaths and injuries by countries in the region. During one training, Eugênia Maria Rodrigues, regional advisor for road safety at the Pan American Health Organization, said that “in some hospitals, 70% of the beds are occupied by road traffic victims.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has placed further pressure on cities to create new and safe environments for travel. Cycling, in particular, has skyrocketed globally, compelling cities to quickly design pop-up bike lanes that are flexible and adaptable to existing street space.

Many participants in the Vision Zero Challenge wondered how to win political support for making these bike lanes permanent. Giovanni Zayas, an active mobility consultant at the World Bank Group in Mexico, said that the importance of telling a story cannot be understated. “We need to show our leaders that these are initiatives being demanded by the people,” he said, “by the residents of the cities that they lead.”

Harnessing the Public’s Voice

Community engagement is a key part of building political support for road safety changes. Alongside ensuring that the needs of the most vulnerable are met, such engagement offers a powerful tool for convincing leaders and changing user behavior.

Johanna Vollrath, executive secretary of the National Traffic Safety Commission in Chile, underscored the value for Latin American cities in particular of “having [the most vulnerable users] as a partner in demanding measures for speed management,” as well as other road safety initiatives.

Several experts recommended prioritizing the voices of children and young people in seeking to persuade policymakers to translate Vision Zero commitment to action. Implementing child-friendly measures such as low-speed and safe school zones, safe walking and cycling infrastructure, and accessible green space helps make a city safer and more sustainable for everyone, not just children. “It’s very hard to say no to children,” said Annie Peyton, senior program associate at NACTO. “It’s this twofold approach for focusing on children, making really beautiful, wonderful educational spaces, while simultaneously making streets that work for everybody.”

Building grassroots support for road safety takes time and has to begin from a well-designed communications and engagement strategy. Throughout the Vision Zero Challenge, experts advised cities to focus on specific design changes being implemented to avoid public confusion about the Vision Zero approach. Sara Whitehead, a public health and preventive medicine consultant, emphasized that “trying to have a public communication effort about a framework or a paradigm shift is unhelpful. Community communications need to be concrete and specific.” A strong communications plan can also rally political backing by educating city officials in addition to the public.

As the Vision Zero Challenge moves into its second year, the participating cities find themselves equipped with more tools, but also faced with new challenges in coping with COVID-19. Using what they have learned throughout 2020, many are well-positioned to propose, design and execute new road safety initiatives. Moving forward, the Vision Zero Challenge Partners, including WRI, will continue to provide support to these cities and others as we seek to help cities adapt and transform their streets.

Hannah Ohlund is an Urban Mobility Intern at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.