Cycling, a sustainable, healthy and low-cost mode of travel, has seen a resurgence in popularity during the pandemic as cars and buses stayed off the roads. During the lockdown in the UK, cycle-to-work schemes saw a 200% rise in bicycle orders from emergency workers. In India, according to the All India Cycle Manufacturers Association, the cycling industry is expected to grow between 15-20% in 2020, from the previous year’s growth rate of 5-7%.

With traffic levels in Indian cities returning to almost pre-pandemic levels, it is important to keep the momentum for cycling going. Cities are actively planning infrastructure to encourage and foster non-motorized forms of transportation, such as walking or cycling, among commuters.

Cities should explore implementing public bike sharing (PBS) systems, a flexible transport service where users can rent a bicycle for a short period of time, making it a low-cost, sustainable and socially distant mode of commuting.

How Can PBS Systems Improve Cycling in Cities?

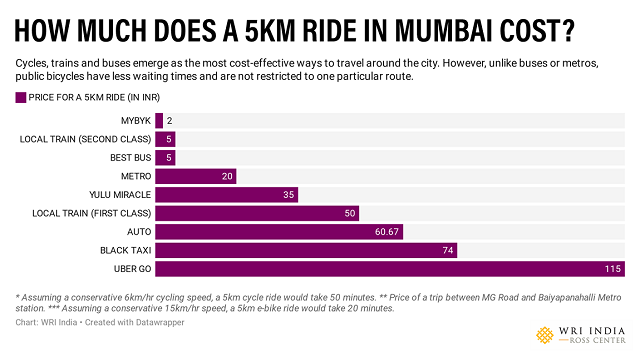

About 35% of vehicular trips in India are short trips (less than 5 kilometers) and form a huge potential market that can use bicycles to travel. PBS allows citizens the flexibility of renting and sharing bicycles for short trips at nominal rates, without the hassle of maintaining a personal bicycle.

Most PBS users travel shorter distances on bicycles (around 2 kilometers). PBS schemes located at public transport hubs in areas with low connectivity can help expand the reach of these services by providing first- and last-mile connectivity. Additionally, through innovative pricing models like long-term subscriptions, PBS systems provide affordable transit for a wide range of users.

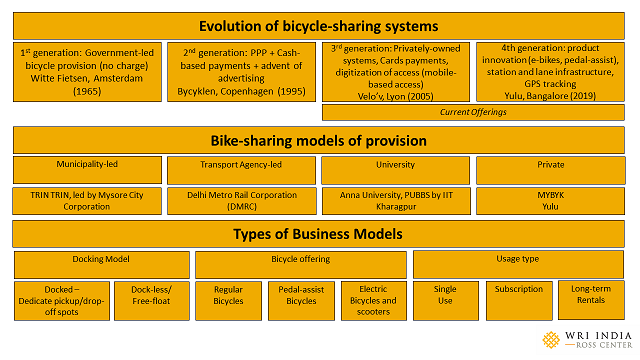

PBS schemes usually have different types of bicycles, including regular, geared, electric or pedal-assist, and different rental models, such as one-time rental, subscriptions and long-term rentals. Municipalities often deploy PBS as a part of citizen-centric services, while transport agencies, whose primary job is increasing ridership, deploy these schemes as feeders to their main transportation modes, such as buses or metros.

In Mysuru, Trin Trin, an initiative of Green Wheel Rides, has 450 bicycles across 48 docking stations and provided about 1,000 rides per day before COVID-19. Currently, the PBS offering is seeing 8-10 new registrations per day (usually recreational riders) and providing 300-500 rides a day.

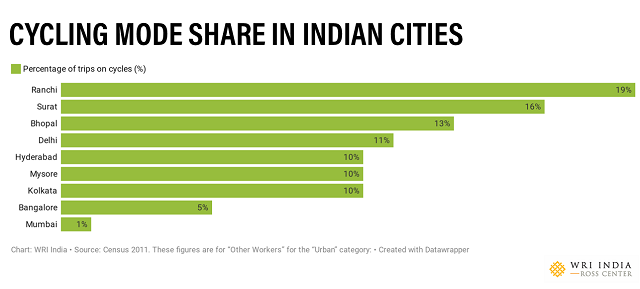

Besides Mysuru, Indian cities like Bhopal and Kochi have also implemented PBS systems. However, many still struggle with challenges like lack of funds for walking and cycling projects, mismatched objectives, or simply the lack of an existing cycling culture and ecosystem.

Challenges with PBS in India

A major stumbling block is the business viability of PBS projects so far. When cycling enterprises and systems initially started taking shape in India in 2008-09, they primarily focused on implementing large-scale PBS in cities like Pune, Delhi, Coimbatore and Bhopal with conventional bicycles, while focusing on smaller pilots in other Indian cities.

In Mumbai, bicycles formed an underwhelming 1% of all trips, far lower compared to other Indian cities. Through the Station Access and Mobility Program (STAMP), a challenge organized by WRI India and the Toyota Mobility Foundation with the Mumbai Metropolitan Regional Development Authority and Mumbai Metro, the city has introduced bicycles at multiple metro stations to provide more sustainable last-mile connectivity.

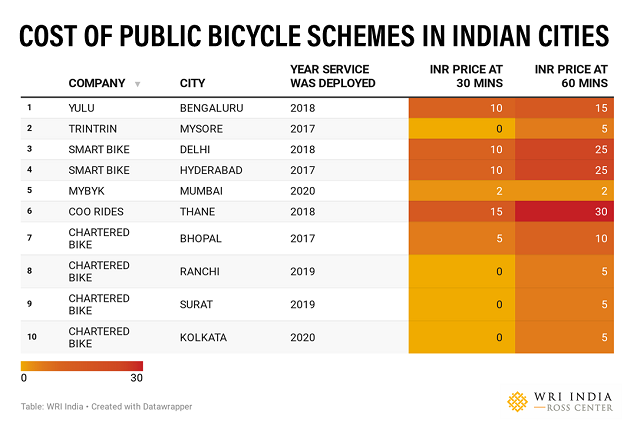

When a PBS project is launched in a new city, it tends to attract interest from recreational and curious riders first, often driven by promotional discounts. However, the business model necessitates high uptake by others, like commuters, fast. There are high capital expenditures to set up stations and vehicles, high operational costs to keep stations stocked with vehicles, but low rental charges (India being a price-sensitive market, as per a WRI India discussion with bicycle operators). In many Indian cities, low uptake by consumers resulted in enterprises pulling out of markets and cutting their losses early.

To understand the financial requirements of running a PBS, we referred to a Detailed Project Report for a plan in Pune that was drafted in 2017, with a plan for 4,500-5,000 bicycles across 388 stations. Capital costs of building infrastructure and buying bicycles were pegged at between INR 481-731 million ($6.5-10 million) and recurring costs (operational, maintenance, etc.) between INR 124-166 million for the first year. However, revenue was estimated at only INR 40 million.

In Pune, while projected costs decreased markedly over the years, the difference between revenue and operational costs remained significant, starting at more than INR 27,000 per bicycle in the first year and INR 16,000 in the seventh year. Similar numbers were calculated in a study for Panaji, showing that unless supported by infrastructure and a cycling culture, such initiatives can fail to make an impact.

Opportunities Ahead

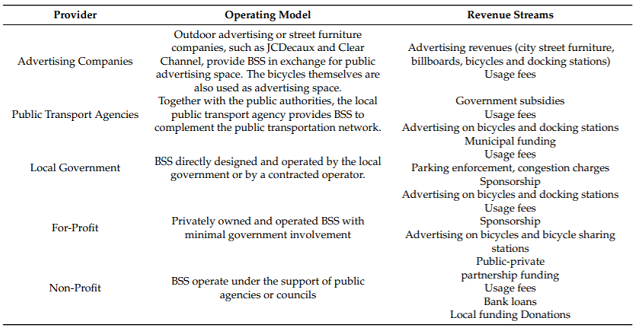

The best approach to making PBS systems successful is to develop a strategy that can identify the right mix of providers, operating models and revenue streams that is cross-governed and deployed as a value creation for end users and for service generators. While PBS operators in India have experimented with some strategies in silos, a more participative approach by city stakeholders to deliver holistic solutions – and value to diverse actors – is important.

In September 2020, WRI India and Karnataka’s Directorate of Urban Land Transport conducted a focus group discussion with Indian bicycle operators who underscored the need for greater government intervention in creating infrastructure, setting policies and co-funding PBS schemes. This is a follow up to DULT’s efforts to boost cycling in the city after their innovative permit model for PBS provisioning in 2018.

So far, governments have taken a passive role and relied more on private investment, which has been successful only in a few counts. The Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs suggests that more government investments in pilot projects can help determine the best financial model for building and maintaining PBS systems in India.

A more commuter-centric approach also needs to be taken in order to create a proper end-to-end PBS system that attracts and maintains riders, focusing on ensuring safety, identifying areas more conducive to cycling, and experimenting with innovative customer acquisition models.

Prateek Diwan is a Senior Associate for Sustainable Cities and Transport at WRI India.

Anya George is a Project Associate for Sustainable Cities and Transport at WRI India.