When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, concerns surrounding virus transmission on public transportation led many to choose alternate mobility options – most notably, cycling. Cycling gained popularity for both recreational use and commuting, a trend especially evident in the United States, Mexico, Colombia, Germany and France. In France, Germany and the United States, weekly average bike ridership was up 4%, 7% and 20%, respectively, from 2019.

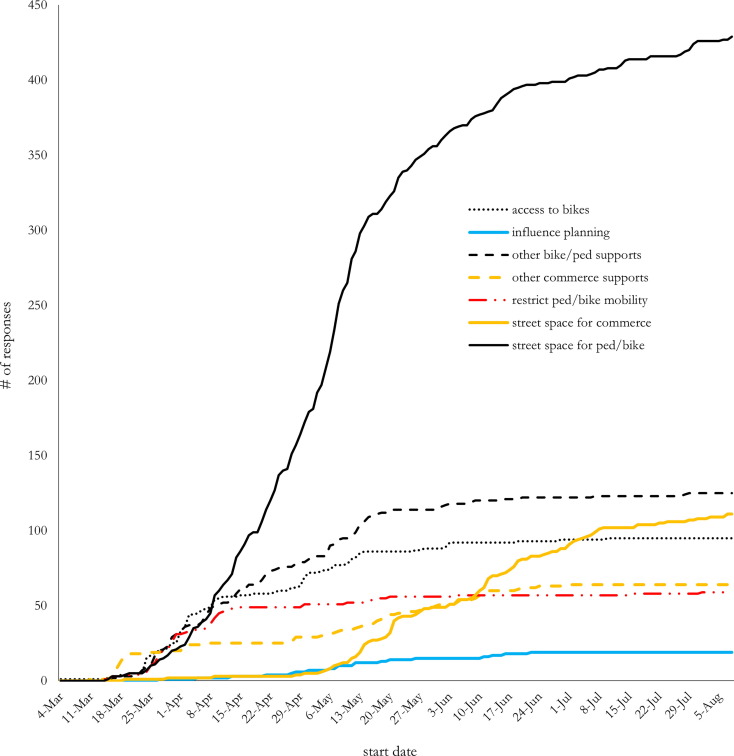

To accommodate these changing mobility patterns, many cities set up new bike lanes. In Latin America, Bogotá created an 84-kilometer network, Lima added 46 kilometers, Buenos Aires announced plans for 60 kilometers and Paris added 50 kilometers. One recent study analyzing more than 1,000 COVID-related mobility actions by 500 cities, states and national governments around the world from March to August 2020 recorded more than 400 incidences of street space reallocation for walking and biking.

But not all bike lanes are created equal. Pop-up lanes do not always have the safety features – like safe speeds, protection from motor vehicle traffic and network integration – needed in the long run. Of the new commitments by Bogotá, Lima, Buenos Aires and Paris, only Buenos Aires’ are designed to be permanent, as of this writing – and only 17 of 60 kilometers have been completed yet.

As cities and countries move in and out of lockdowns, developing permanent, safe cycling networks can be an effective, sustainable solution to both maintaining and growing economic activity while curbing COVID-19 infections. As part of recent virtual trainings for the Vision Zero Challenge, an initiative supporting 24 cities in Latin America and the Caribbean on full realization of Vision Zero and the Safe System approach to road safety, we recently explored key considerations for making pop-up cycling infrastructure permanent. Here are three key steps to transforming cycling infrastructure beyond the pandemic.

1. Adapt Existing Road Space Through Tactical Urbanism

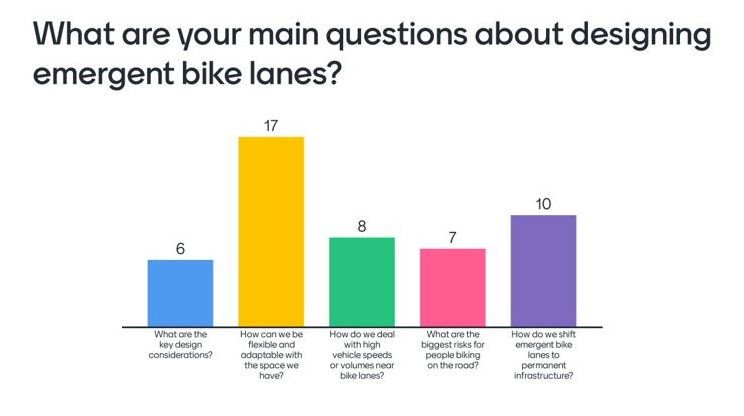

Vision Zero Challenge participants were especially concerned with how bike lanes could be adapted to the limited road space available in their cities.

Anders Hartmann, senior road safety advisor for Asplan Viak, offered insights from Oslo’s experience in adapting existing infrastructure. Oslo is mostly composed of narrow streets, Hartmann explained, but the city made space for bike lanes by converting some two-way streets to one-way and made traffic safer by narrowing lanes and reducing turning radii to force drivers to slow down. Oslo’s success story is particularly significant because it achieved zero pedestrian, cyclist and child road fatalities in 2019, the first such milestone by a large city.

Pop-up bike lanes are another example of using temporary tactical urbanism to repurpose road space and create infrastructure that is adaptable and flexible given limited space. Tactical urbanism allows cities to test impact by monitoring use, ridership, safety and effects on the city’s mobility system before adjusting the design to make these changes permanent. Based on WRI’s extensive experience with “complete streets” interventions, such an approach can build community owernship and buy-in at low cost, creating the support and evidence needed to make permanent changes easier.

2. Reduce Speeds and Calm Traffic

Panelists in the Vision Zero Challenge training said that cities looking to implement permanent bicycle lanes must consider speed management strategies to ensure an efficient and safe mobility network for cyclists. Speeds below 30 kilometers per hour dramatically reduce the risk of cyclist or pedestrian fatalities, from 85% at 50km/h to 10% at 30km/h.

Many cities have already moved to reduce speed limits, especially in areas where cars, cyclists and pedestrians are frequently in conflict. Bogotá has been reducing speeds for several years now. And in Brussels, a citywide 30 km/h speed limit went into effect at the start of 2021 in a bid to increase safety for vulnerable road users. Many other European cities have also worked to slash speed limits to 30 km/h over the past year, including in Spain and France.

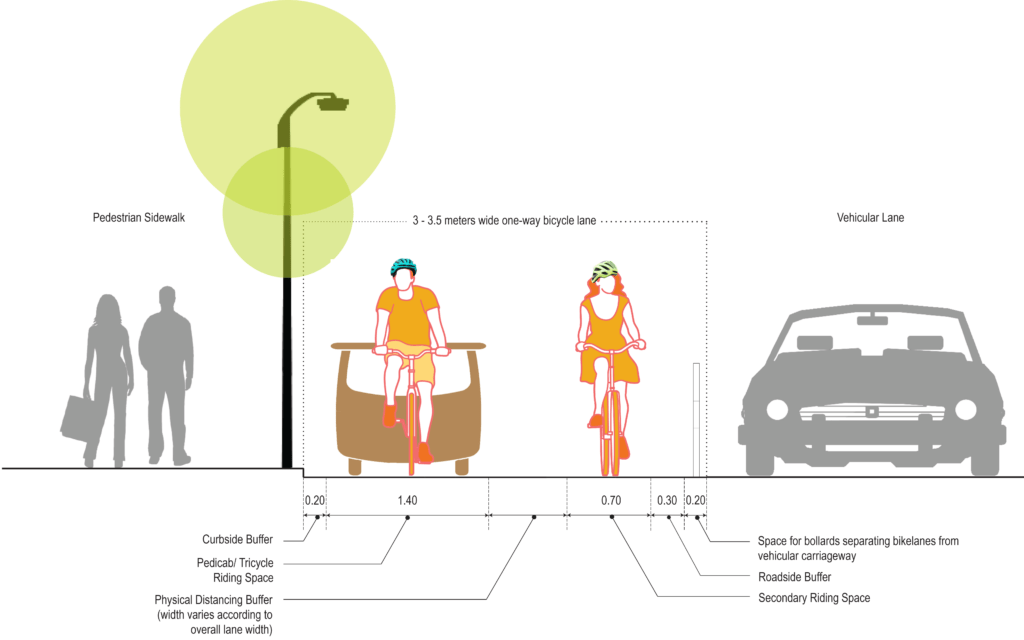

However, speed limit reductions alone are not enough. In the U.S., speeding rose dramatically during COVID-19 lockdowns. Physical traffic-calming measures such as raised intersections and crossings, speed humps and cushions, fewer lanes, and narrowed streets at intersections help to practically limit vehicle speeds. Once proper speed management measures are in place, cities need to consider the appropriate cycle lane design for each road type and speed limit when making temporary infrastructure permanent.

Certain lane design features are crucial to improve safety. These include a minimum width of 3 meters for one-way bike lanes on arterial roads; lane placement in the same direction as adjacent vehicular traffic and the sidewalk; and lane entry and exit that provide safe spaces for slowing down, stopping and dismounting. One 13-year study analyzing traffic crash data from 12 major U.S. cities found that separate, protected bike lanes resulted in 44% fewer deaths and 50% fewer injuries compared to cities that had not implemented such measures.

3. Link Cycling Infrastructure to Long-Term Objectives

As Alexandre Santacreu, policy analyst at ITF, said during the training, “If you are building safe infrastructure which connects people to places, it should be obvious that it remains permanent.”

Panelists emphasized that when implemented in alignment with long-term development plans, safe, permanent cycling infrastructure can play a crucial role in cities’ visions for sustainable, accessible and equitable mobility in the post-COVID era. Quality cycling infrastructure in all neighborhoods of a city, especially low-income areas, would incentivize a low-carbon mobility option and help to improve local air quality while improving access and increasing connectivity.

So how can cities tie cycling infrastructure to long-term objectives? The growth of cycling in the Netherlands provides one classic example, also borne out of a moment of crisis. During the OPEC oil crisis in the 1970s, Dutch cities put on car-free days to discourage private vehicle use. As cycling gained popularity, widespread implementation of permanent bike networks followed, eventually leading to the widespread cycling infrastructure and prominent cycling culture that exists today. Political will, accompanied by community involvement and support in decision-making processes, proved effective for the Dutch in maintaining cycling as a core piece of long-term urban development.

Today, some city leaders are already making cycling networks a priority in their post-COVID sustainability and development plans. In September, Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo announced that the city’s 50 kilometers of pop-up bike lanes would be made permanent in the aftermath of the pandemic. Hidalgo also revealed that Rue de Rivoli, one of Paris’ busiest streets, is en-route to becoming a multi-lane bike highway. Not only do these plans address changing mobility patterns, but they are in line with the city’s climate and air pollution reduction goals.

As when implementing any infrastructure changes, cities should allow for continued evolution when integrating temporary cycling networks. Engaging with local communities, monitoring ongoing use, progress and results of bike lane changes, as well as quick responses to the issues and needs of bike lane users, are all important. Cities should aim to be flexible with the space they have and implement speed management strategies simultaneously in order to successfully apply the Safe System approach to road safety. In doing so, cities can be more resilient and move urban mobility patterns in a more sustainable and equitable direction.

Camilla Zanetti is an Urban Mobility intern at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.

Alejandro Schwedhelm is Urban Mobility Associate at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.

Claudia Adriazola-Steil is Deputy Director of Urban Mobility and Director of Health and Road Safety at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.