Owusu lives with his wife and four children in the Tantra Hills neighborhood of Accra, Ghana, where he shares his residence with five other tenants and their families. The house has a toilet and electricity, but the costs for both are exceedingly high. The house is not connected to the municipal water supply, so Owusu must buy water from expensive private vendors. His electricity bill, at $50 per month, costs more than his $33 rent. With a regular monthly income of $175, Owusu lives in perpetual fear of being evicted from his home if his rent increases or water or electricity costs rise.

Additionally, Owusu’s neighborhood is not easily accessible by public transport. The nearest bus stop is about one kilometer away, and he typically waits up to 30 minutes for the bus. His commute to work at the Shell gas station takes about 2 hours without traffic. He leaves his house by 4:30 in the morning, every Monday to Saturday, to beat the rush.

Owusu is one of the 1.2 billion city dwellers worldwide who lack access to basic services like running water and sanitation, electricity, decent housing, transport and other amenities. The synthesis report of the World Resources Report series, Towards a More Equal City, finds that one in three urban residents globally are under-served by municipal services. This divide between those who have access to services and those who do not is worsening due to rampant, poorly managed growth in cities.

The cumulative cost of this urban services divide impacts everyone in the city, not just the under-served. Without access to municipal services, residents of all income groups are forced to make their own arrangements to meet their basic needs for housing, water, sanitation, energy and transport. These alternative services can be inferior to — and more expensive than — the municipal services available to others and they can be damaging to the environment, but often they are the only option available. The urban services divide burdens the entire city with lost productivity, higher expenditures, environmental degradation and poor health. But it doesn’t have to be this way.

The synthesis report identifies seven crucial transformations that reimagine urban service provision, include the excluded and create the right enabling conditions for lasting change. It shows that focusing on siloed, sector-specific approaches will not help cities facing unsustainable, unequal, ad hoc development that traps most people in poverty. Instead, these cross-sectoral transformations can lift residents out of poverty while creating economic, environmental and social benefits for all.

Here are the seven cross-sectoral transformations for equitable and sustainable cities:

1. Infrastructure Design & Delivery: Prioritizing the Vulnerable:

In many cities in the global south, urban infrastructure design and development has ignored the growing number of people living in informal settlements or in the disconnected urban periphery. These areas often lack access to basic services, leaving residents to make their own arrangements — often illegal, informal or costly in terms of time, money, health, and environmental costs. This problem is likely to worsen without action, as an estimated 1.6 billion people will lack adequate housing by 2050. In addition, climate change puts vulnerable populations and infrastructure at greater risk. If global temperatures increase by 2 degrees C, 2.7 billion people, or 29% of the global population, will be exposed to moderate or high climate-related risks by 2050. Of these people, 91% to 98% will be living in Asia and Africa.

Municipal infrastructure must be designed and delivered to prioritize neglected populations, address existing backlogs to basic services, minimize carbon lock-in and anticipate future risks. Integrated planning and cross-sectoral collaboration can help generate cascading benefits, such as citywide improvements in water quality from investing in improved sanitation for the under-served. Cities also have the opportunity to chart a new model of infrastructure development that limits carbon emissions and enhances climate resilience.

Medellín, Colombia, invested $35 million to build Metrocable’s K line, a circulating releasable single-rope gondola system that directly benefits 150,000 residents from Medellín’s peripheral neighborhoods. In some cases, this investment reduced one-way commutes from 2 hours to 30 minutes. This showed how investing in safe, non-polluting and affordable multimodal public transportation services, including cable cars, can tame congestion and connect poor, peripheral or hillside communities with jobs in the city center. Additionally, investing in mass transit and active transport infrastructure could potentially reduce greenhouse gas intensity in the transport sector by up to 50% by 2050, compared to 2010 levels.

2. Service Provision Models: Partnering with Alternative Service Providers

Informal service providers, such as minibus drivers or water vendors, provide vital services where municipal public services are not available. These services are often expensive, poor quality or, in some cases, harmful to people and the environment; alternative water supplies may be unfit to drink, alternative energy sources may be dangerous and alternative transport can contribute to congestion and pollution. City authorities in the global south often ignore informal services because they do not have the capacity or political will to set quality standards and enforce regulations to protect consumers and the environment.

Rather than ignore alternative service providers, cities can integrate these alternative services into their plans for short- and medium- term development including through partnerships that deliver accessible services to more people. Our Kampala case study shows how the city government successfully partnered with small businesses, community groups and the national water and sanitation utility to improve fecal sludge collection from pit latrines. This partnership supported the use of affordable, non-traditional technologies and created new livelihood opportunities for community residents.

Citywide impacts are schematic. Source: Authors

3. Data Collection Practices: Improving Local Data Through Community Engagement

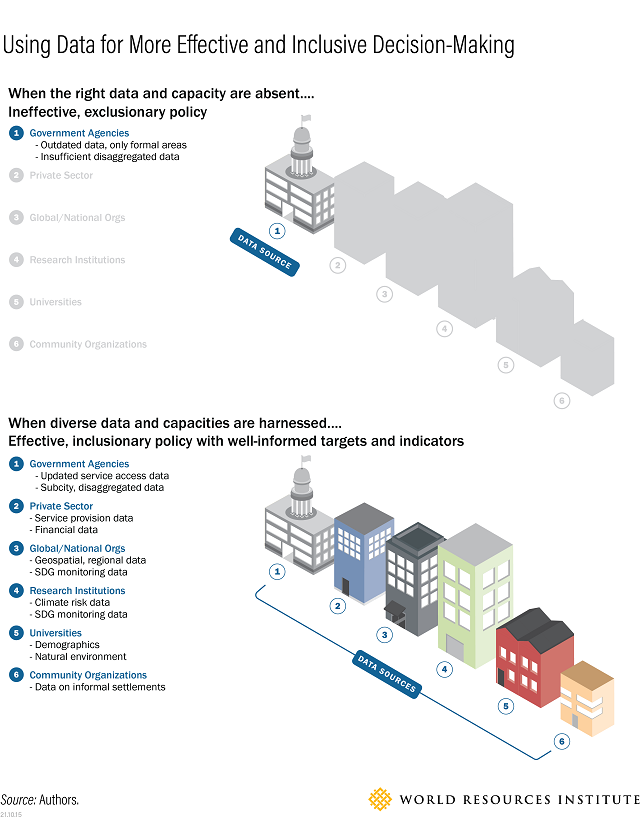

A city cannot solve a problem that it doesn’t fully understand. Despite all the data that exists today, many cities do not have granular, local data to help identify where and how vulnerable populations live. Even where data exists, cities often lack technical capacity to manage, share and use data to guide their decision-making.

New technologies, partnerships and community engagement can generate better local data for decision making and improve governance. In a recent seven-year study, researchers mapped informal settlements in Bengaluru, India, with satellite imagery, machine learning and ground truthing efforts. This study recorded about 2,000 informal settlements in the city, while government records showed fewer than 600. This information can enable the city to better deliver services to these settlements.

4. Informal Urban Employment: Recognizing and Supporting Informal Workers

Globally, 2 billion workers operate in the informal economy, representing 50% to 80% of the urban workforce in the global south. These informal workers supply many vital goods and services to cities, yet they receive relatively little attention. Past research mainly focused on boosting formal sector productivity, resulting in very little available data on informal employment. Cities with large informal sectors tend to ignore them, treat them as liabilities or get rid of them, leaving both informal workers and the people who depend on them vulnerable.

Recognizing and supporting informal workers and expanding their access to public space, services, customers and social safety nets can improve livelihoods and economic resilience of cities. For example, in Indian cities such as Surat and Ahmedabad, the Mahila Housing SEWA Trust negotiated with city agencies and leveraged city funds on behalf of informal workers. These funds were used to upgrade housing conditions and access solar energy technologies to run refrigerators, soldering irons and sewing machines for home-based businesses. These changes raised incomes, saved money and lowered energy consumption.

5. Financing and Subsidies: Increasing Investment and Targeting Funds Innovatively

Cities are failing to make necessary investments to fill gaps in core services, which can lead to even larger costs in the future. According to the World Health Organization, providing all city dwellers with clean drinking water would cost $141 billion over five years, but unsafe water and inadequate sanitation currently cost 10 times that much, mostly in time and health costs.

Cities, countries and investors need to increase investment and target it innovatively to fill the gap in affordable urban services. Participatory budgeting processes as discussed in our case study of Porto Alegre, Brazil, is one way to do this to meet local needs. Higher national investment with targeted subsidies can also get money where it is needed most, while innovative financing instruments and creative payment methods can increase affordability. PROTRAM, a federal program in Mexico, is leading the way in these kinds of investments. They offer grants to city, state and regional government agencies for up to 50% of the infrastructure cost of urban mass transit projects. These investments have resulted in high-quality mass transit, which is low-carbon and increases access for middle- and lower-income people who do not own private vehicles.

6. Urban Land Management: Promoting Transparency and Integrated Spatial Planning

Urban areas are expected to grow by 80% between 2018 and 2030. Most cities are growing outward unsustainably, with a rising number of informal settlements. This will also increase spatial inequality, or unequal access to services and opportunities based on location. City governments often lack the authority, resources or technical capacity to plan for this growth, so development is driven by private landowners’ profits instead of public interest.

Transparent, well-regulated land and housing markets, and integrated spatial planning are central to delivering services equitably and managing growth sustainably. This includes cross-sectoral interventions to upgrade existing informal settlements in place in secure locations, and provide affordable access to services, as described in our case study of Surabaya, Indonesia.

The Mukuru slum outside of Nairobi is home to more than 100,000 families, living on 647 acres of land that is divided among 230 different owners. The municipal government designated Mukuru as a “special planning area” that required a comprehensive development plan prepared in partnership with the community before any new resources could come to the area. The local government and NGOs worked together to create an eight-sector development plan that prioritized water and sanitation due to their immediate impact on public health. This collaborative process shows how cross-sectoral spatial planning can meet the needs of under-served communities.

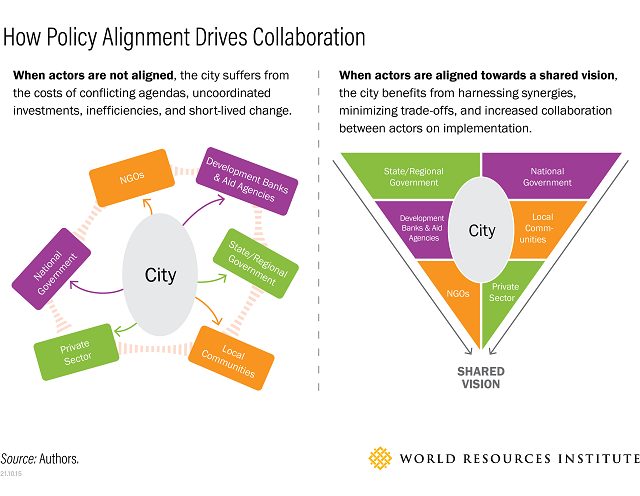

7. Governance and Institutions: Creating Diverse Coalitions and Alignment

Cities do not always have the power or resources to make needed changes on their own. For example, access to some urban services depends on metropolitan or regional agencies who plan the networks. Cities need a shared vision and aligned policies across government levels and departments, but as cities have grown rapidly, existing institutional structures and governance processes have become inadequate to meet their needs. As a result, these structures are no longer corresponding to the realities of city life.

Coalitions of diverse actors can galvanize political action, promote inclusion and achieve lasting change. Aligning national and local policies around a shared vision can reduce costs, prevent inefficiencies and help cities achieve strategic objectives.

Towards a More Equal City includes case studies on Guadalajara, Mexico; Pune, India; and Kampala, Uganda. These studies show how coalitions of civil society and small business groups working together with key government officials produced improved public space in Guadalajara, better transportation and solid waste management in Pune and increased access to sanitation for poor communities in Kampala. Our case studies on Ahmedabad, India, and Johannesburg, South Africa, show that aligning policies across scales of government and local agencies are helping create affordable housing in well-connected locations of the city.

Making Transformative Changes Today for Sustainable Cities Tomorrow

Global efforts to fight poverty and climate change hinge on whether urban populations have access to services and opportunities. The COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated the urban services divide, providing a sobering look at the inequality between those who have the money and choice to remain safe and employed, and those who do not. The decisions made today can embed poverty, deny opportunity and widen the urban services divide in ways that grow harder and harder to reverse. They also can lock in high energy consumption and carbon emissions for decades to come, worsening the risks of climate change.

It is not too late to change course. Prioritizing equitable access to core urban services can offer an effective entry point, a blueprint and a way forward toward more equitable and sustainable cities for all.

This blog originally appeared on WRI’s Insights.

Maeve Weston is Research and Engagement Specialist at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.

Robin King is Director of Knowledge Capture and Collaboration at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.