Since the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, cycling has become an even more popular, resilient and reliable travel option, and pop-up bike lanes have been increasingly common in major cities around the globe. Between March and July 2020, 394 cities, states and countries reallocated spaces for people to cycle and walk more easily, efficiently and safely.

Take the example of Paris, France, where mobility systems were redesigned to include cycling infrastructure at unprecedented levels, with plans for more than 650 kilometers (403 miles) of new cycleways.

A new guide sets out planning and design guidelines to help cities implement bike lanes quickly, effectively and safely.

Ensuring Pop-up Bike Lanes are Safe and Efficient

Led by WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities in collaboration with the Dutch Cycling Embassy, the League of American Bicyclists, the Danish Urban Cycle Planning, and Norway’s Asplan Viak, the guide focuses on a key consideration: whether and how to separate cyclists from the street.

Pop-up bike lanes are typically implemented with temporary materials to segregate a traffic lane and create a space just for cyclists. But despite being initially temporary, any new cycling infrastructure must be designed and implemented thoughtfully and to the highest standards to reduce the risks that cyclists might face. According to the World Health Organization, 41,000 cyclists die in road traffic-related incidents worldwide each year, around 3% of global road traffic deaths.

How and how much to separate cyclists from traffic depends a lot on the speed vehicles are travelling. Lowering speed limits on city streets through simple design changes and speed-calming measures could help prevent or reduce pedestrian and cyclist injuries. And in certain high-speed street contexts, more segregation between cyclists and traffic is necessary to prioritize cyclists’ safety.

How Can Cities Make Roads Safer for Cyclists?

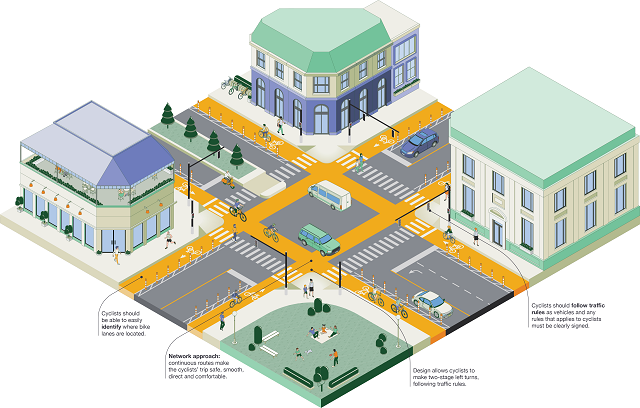

Here are four approaches to help cities implement safe bicycle infrastructure in varying street contexts and speeds:

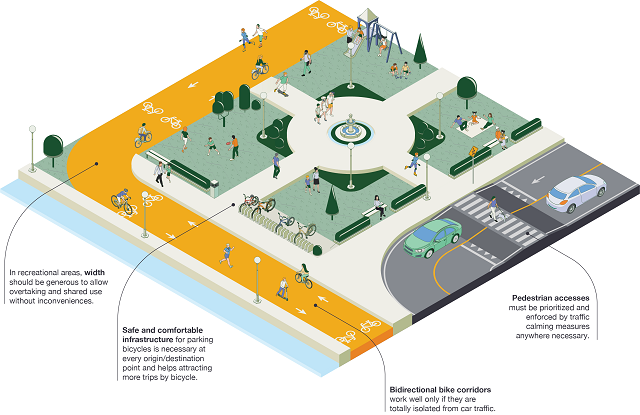

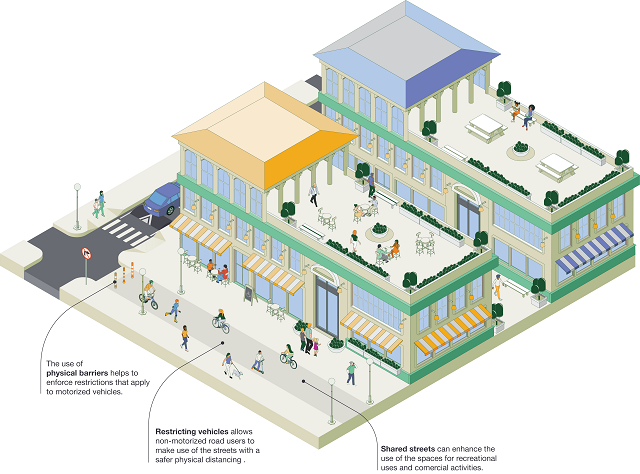

1. Bike Lanes in Car-Free Zones for a Connected, Livable City

In car-free zones, cyclists can safely share the street with pedestrians and other non-motorized road users in general. Bidirectional cycle lanes are a great addition to recreational and shared areas and can help transform small streets into inviting public spaces, providing a stress-free, comfortable and safe space for cyclists.

While bidirectional bike lanes work great in car-free environments, they are not recommended in any other street contexts as they increase the risk of accidents — especially at intersections where drivers may have difficulty seeing cyclists coming from both directions.

Every city needs a fair share of car-free zones embedded in its street network to improve connectivity and livability for people who walk or cycle, or other non-motorized users. Take the capital city of Ljubljana, Slovenia, which has been redesigning its city center to accommodate car-free zones to encourage pedestrians and cyclists. Since its implementation began in 2007, there has been a steady increase in pedestrian and cyclist footfall, while carbon dioxide emissions dropped by 70% and noise has dropped by an average 6 decibels.

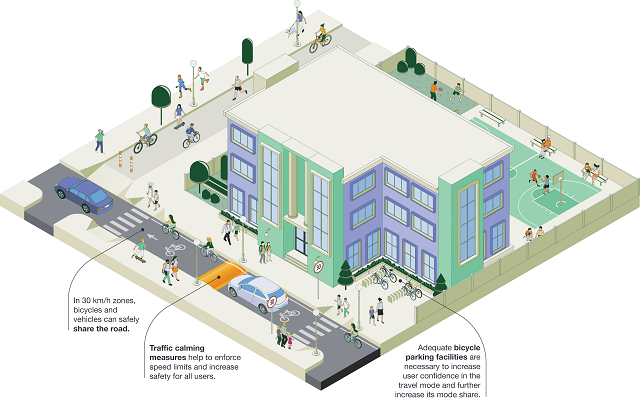

2. Bicycle Boulevards: Where Bikes Are King of the Road

Bicycle boulevards are streets with low traffic volumes and speeds, designed to give cyclists travel priority. These streets use signs, pavement markings, and speed and volume management measures to discourage car journeys and create safe, convenient bicycle crossings on major, busy streets. With maximum speeds of 30 km/h (18 mph) and less than 2,000 vehicles passing through each day, cyclists can safely share the roadway with motorized road users.

In Portland, the United States, bicycle boulevards have achieved the challenging objective of placing cyclists above motorists in the hierarchy of road users. Their success is owed to diligent management of motor vehicle volumes and speed, a broad and connected network, and standardized wayfinding and design that allows all users to understand the unique hierarchy for these streets. Its success has led to Portland developing more than 70 miles of bicycle boulevards.

These kinds of streets are the preferred solution in residential, school or recreational areas, and in any place where access by car is necessary but traffic levels are low — primarily for non-motorized or more vulnerable users. Low-speed zones must include a proper combination of traffic signs, pavement markings, and traffic-calming measures that remind drivers constantly to watch for cyclists and that encourage cyclists to use the roadway freely.

3. Pop-up Bike Lanes Can Use Temporary Methods to Separate Cars and Cyclists

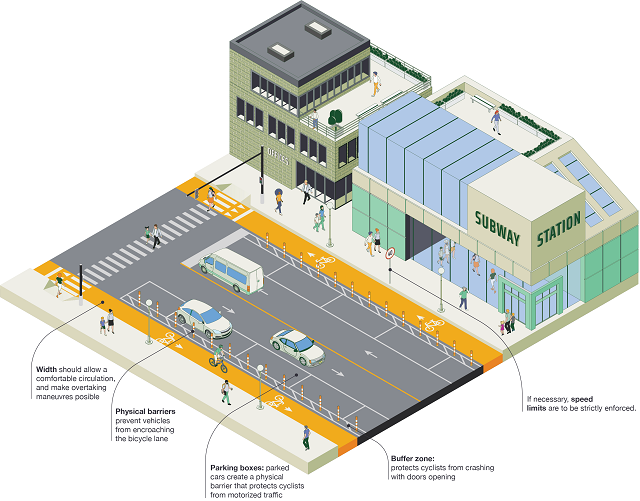

On streets with high speeds (of over 30 km/h) and where up to 6,000 vehicles travel each day, it’s necessary to protect cyclists from passing cars with a well-marked and dedicated space for them to cycle. But it takes time to develop high-quality cycling infrastructure. In these areas, pop-up bike lanes are a good first step towards developing something more permanent. Temporary elements such as visible paint, reflective plastic cones, freestanding barriers, and light-duty bollards should be placed between the bike lane and the vehicle lane.

These bike lanes must be “one-way” only and follow the same direction of car traffic to avoid risk of collision. Evidence suggests that building one-way bike lanes reduces serious injury. In general, safety for all road users can be heightened when pop-up bike lanes are coupled with safe street design and speed management strategies.

In Berlin, Germany, 25 kilometers (15.5 miles) of bike lanes were developed in record time — since April 2020 — using portable elements such as bollards, poles, mobile signs and yellow foil. Appropriate signs and markings help alert drivers of cyclists, familiarize road users of the new street changes, clarify right-of-way, and emphasize vehicular speed limits, like Berlin has done with many of their lanes.

When implementing bike lanes, it’s important to ensure that moving or parked cars do not encroach on the lanes as this can be dangerous for cyclists, especially if they collide with an open car door. If space allows, a buffer zone should be painted between the parking and bike lanes to prevent cyclists from being hit. In general, a bike lane should measure 2.2 meters minimum — enabling two cyclists to ride side by side comfortably.

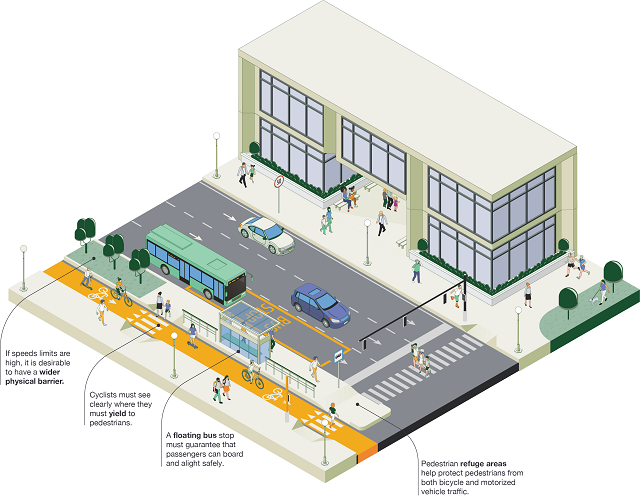

4. For Busier Streets, Bike Lanes Need Heavy-Duty Physical Segregation

Where vehicular speeds reach up to 50 km/h (31 mph) and more than 6,000 vehicles pass by each day, bike lanes must be protected from car traffic with heavy-duty physical separators — such as curbs, bumpers, bollards or barriers. These are designed to protect against damage caused by heavier-weight vehicles or for use in higher-speed environments.

But the barriers used for segregation must not pose a safety hazard for cyclists in case of a crash; polyurethane, heavy-duty plastic or flexible rubber bollards are better than concrete, steel or other hard materials.

Heavy-duty separation options should only be considered once a maximum speed and other traffic-calming measures have been imposed. Designing side curbs mindfully, for example, can prevent situations such as cyclists grazing them with the pedals or the wheels bumping into the curb by accident.

Should pop-up bike lanes be developed in these areas they should also be one-way only and follow the same direction of car traffic. Spaces for cyclists and buses should be clearly demarcated to minimize confusion and accidents, and markings must make clear to cyclists that they must yield. New “floating bus stops”, which channel the bike lane behind the bus stop to separate bicycle traffic and people boarding, alighting, or waiting for transit, in Cambridge, England, are a good example of bus stops built with cyclist safety in mind.

Creating Bike-Friendly Cities for the Future

To make cycling a safe and appealing transport option both now and beyond the pandemic, cities should continue to encourage the use of pop-up bike lanes and, when possible, make them permanent. This will allow the switch to cycling as a viable mobility option to grow, enabling people and cities to enjoy its abundant benefits for physical and mental health, the environment, air quality, economic impact, livability and overall accessibility.

This article originally appeared on WRI’s Insights.

Nikita Luke is a Senior Project Associate for Health and Road Safety at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.

David Pérez-Barbosa is a Mobility and Road Safety Advisor at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.