On July 22, the world experienced its hottest day in recorded history. The global average temperature reached 17.2 degrees C (62.9 degrees F), prompting UN Secretary-General António Guterres to issue a global call to action on extreme heat.

The problem of extreme heat, however, doesn’t exist in a vacuum: When temperatures rise, so too can air pollution levels, as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), an in-depth assessment of the state of climate change authored and reviewed by hundreds of scientists and experts, recognized last year.

Mexico City is one of many urban areas around the globe where this interplay can take hold. Last spring, record temperatures and windless conditions led to a three-day severe pollution alert. The city also activated emergency measures such as limiting traffic to help bring down particulate emissions and ozone levels. It was a dark reminder of the past, harkening back to the 1990s when Mexico City was named the world’s most polluted city. Walking around outside during that time had the same impact as smoking two packs of cigarettes a day.

Since then, Mexico City has taken bold steps to clean the air by introducing measures like prioritizing clean fuels and hastening the shift to electric buses. As a result, the city’s residents are now living healthier and longer lives — on average, three years longer than in previous decades.

But Mexico City faces a new, dangerous threat: longer and more frequent heat waves supercharging its air pollution. And as extreme heat continues to worsen, especially in cities where it is exacerbated by the urban heat island effect, Mexico City and other cities around the world must develop integrated strategies to tackle these dual, correlated challenges.

The Connection Between Heat and Air Pollution

Throughout the thousands of pages of the IPCC’s AR6 report, the authors detailed some of the most alarming climate impacts, including the deeply intertwined relationship between global warming and poor air quality.

Put simply, air pollution levels spike when temperatures rise. This happens in a variety of ways. High temperatures can lead to more frequent droughts and more intense wildfires, both of which increase particulate matter (PM10 and PM2.5). Wildfires also release large amounts of black carbon, nitrogen oxides (NOx), carbon monoxide (CO) and other volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Heat also accelerates biological processes responsible for the degradation of organic waste and wastewater, releasing both air pollutants and greenhouse gases into the air.

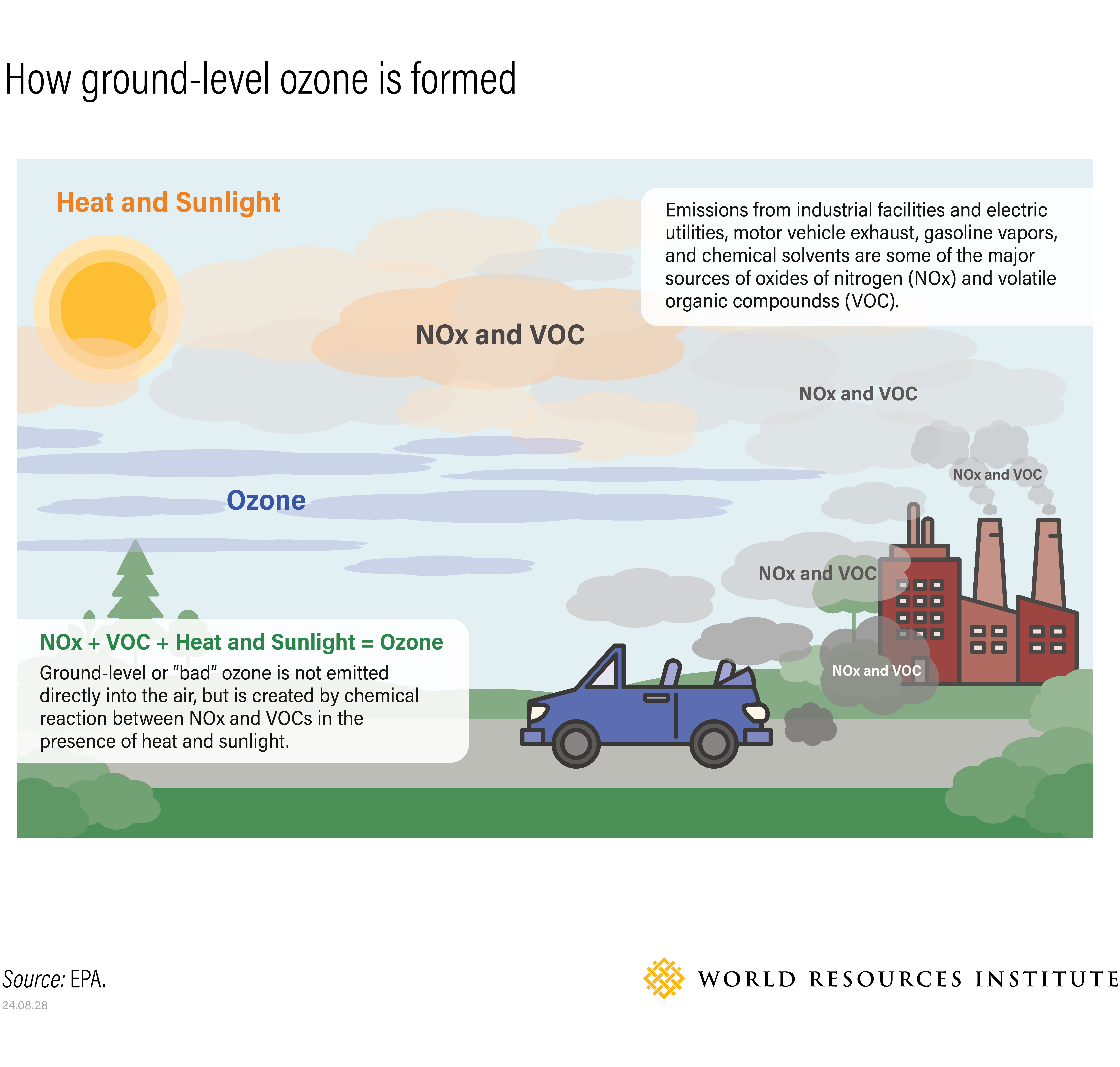

Certain pollutants, however, actually feed on the heat. Ground-level (or tropospheric) ozone, an often overlooked but deadly pollutant, forms when VOCs, including methane, and NOx emissions from vehicles, industrial facilities, waste and agricultural burning and other sources chemically react through exposure to sunlight. Warmer temperatures accelerate these reactions, leading to increased ozone production, which manifests as a harmful haze. As a result, during hotter, dryer, less windy months — and especially during heat waves — ground-level ozone can reach dangerous levels in cities.

Countries around the world are seeing the correlation between high temperatures and high ozone levels. During a heat wave that spread across Europe in July 2022, the ground-level ozone in Portugal, Spain and Italy all registered at least double the 100 micrograms per cubic meter (µg/m³) deemed safe by the World Health Organization. That same summer, China also experienced elevated ozone levels during a heat wave. And a recent study made a broader connection between high ozone and high heat in China, based on ozone levels observed between 2014 and 2019.

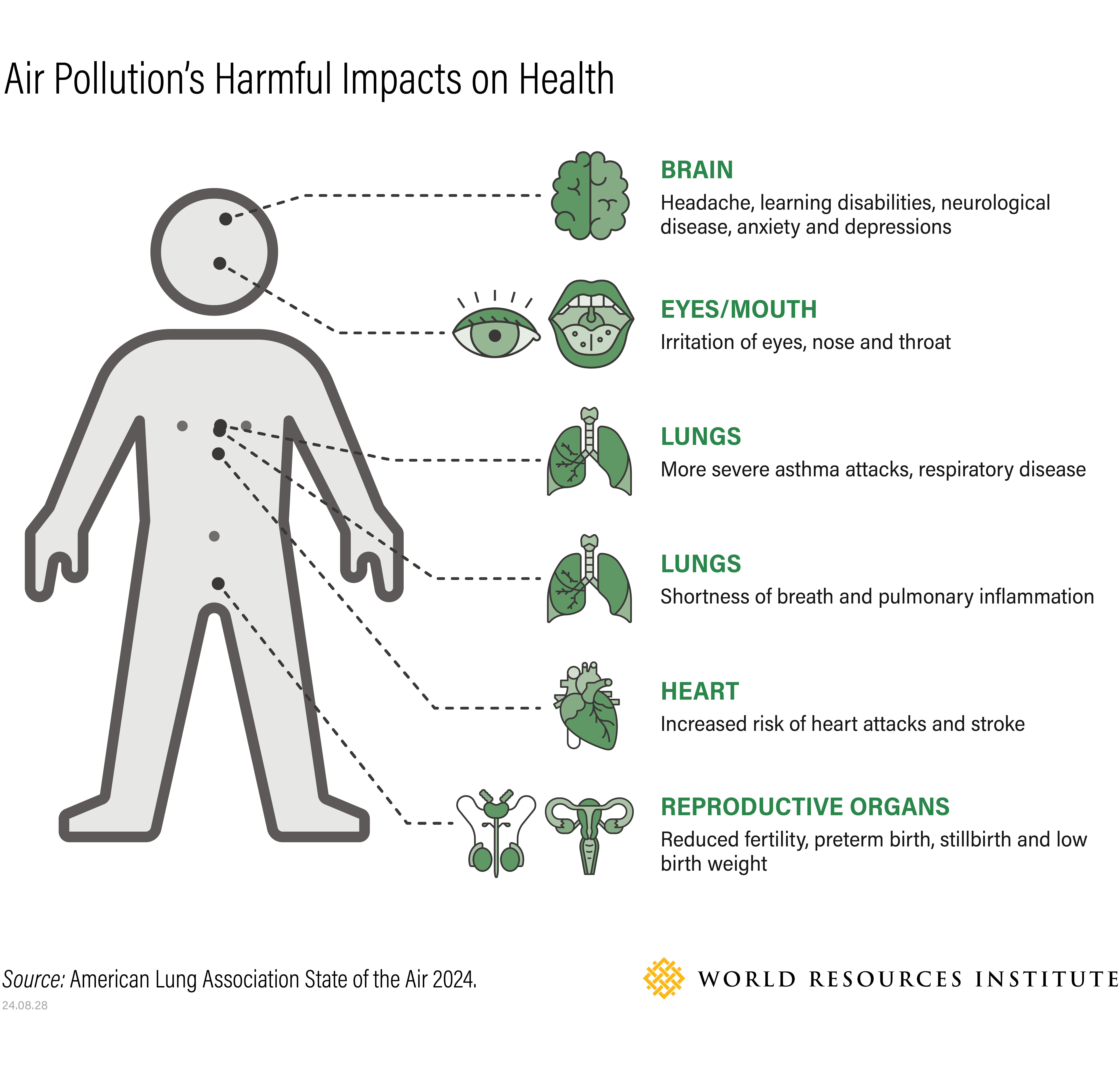

Increased ground-level ozone can pose serious health risks, particularly to vulnerable populations like children, pregnant people and older adults. Ground-level ozone pollution also threatens critical ecosystems like forests by weakening their ability to respond to stresses like drought, cold and disease. It also damages crop production by reducing plants’ ability to turn sunlight into growth and contributes to rising global temperatures by reducing the ability of trees to absorb carbon dioxide.

A Growing Threat to Public Health

On its own, air pollution can risk lives and livelihoods. But when coupled with extreme heat, the results can be even more deadly. The combination of high temperatures and stagnant air created during heat waves makes people more vulnerable to severe health impacts and urban infrastructure more susceptible to degradation.

Air pollution and heat exposure can each have short and long-term impacts on the respiratory and cardiovascular systems. Ozone alone accounted for roughly 490,000 deaths globally in 2021, and long-term exposure to ozone contributed to roughly 13% of all Constructive Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) deaths around the world that same year. And one study attributed air pollution, including PM2.5 and ground-level ozone, to more than 7,000 adverse health outcomes in children, 10,000 deaths and 5,000 hospitalizations a year in Jakarta, Indonesia. Extreme heat accounts for roughly 489,000 deaths globally per year. And, during Europe’s 2022 heat wave alone, more than 60,000 heat-related deaths occurred. More research is needed to understand how those deaths could have also been impacted by exposure to air pollutants.

Studies show that risks to individual health are heightened when air pollution and high temperatures are simultaneously at play. For instance, recent research found that high temperatures can exacerbate physiological responses to short-term ozone exposure. According to a 2022 study, mortality risk on days with combined exposure increases by an estimated 21%. Another study on the effect of heat and ozone on respiratory hospitalizations in California found that lower-income neighborhoods and areas with high unemployment rates were disproportionately susceptible to the combined impacts of heat and ozone.

Children and the elderly are the most vulnerable populations facing this deadly combination. Air pollution is currently the second leading risk factor of death for children under 5 years old. Meanwhile, those aged 50 and older suffer at a higher rate from pre-existing conditions such as COPD, diabetes, stroke and heart disease, and are especially susceptible to high levels of tropospheric (ground-level) ozone. Low- and middle-income countries are also disproportionately affected by ozone, as they account for a significant piece of the total number of deaths attributed to ozone since 2010. As air quality worsens and our planet continues to get hotter, the world needs to take urgent action to prevent, and to treat the most vulnerable from, these impacts.

Solutions to a Deadly Combination

Working to weaken the relationship between heat and air quality is critical for reducing the effects of these combined threats. Tackling the emissions that warm our planet and reducing the pollutants that contaminate our air is critical for addressing the root causes of each problem. But leaders can also take action to more immediately protect residents and build climate resilience.

Health preparedness

As we adjust to rising temperatures, it is vital that our medical systems are able to keep up with the growing number of people affected by heat and air pollution. During heat waves and high pollution events, cities must be prepared to handle an increased intake of people seeking medical attention, especially those with pre-existing conditions who are more vulnerable to respiratory and cardiovascular issues during extreme heat events. By increasing access to medical emergency rooms and live-saving medications, cities can strengthen emergency response capacity and bolster public health infrastructure. Bangkok’s air pollution clinic, dedicated solely to treating patients suffering from air pollution-related illnesses and educating the public about air quality safety, is a potential model for other cities to follow. The more capacity that public health systems have to treat patients suffering from air pollution and heat-related illnesses, the more lives will be saved.

Better air quality forecasting

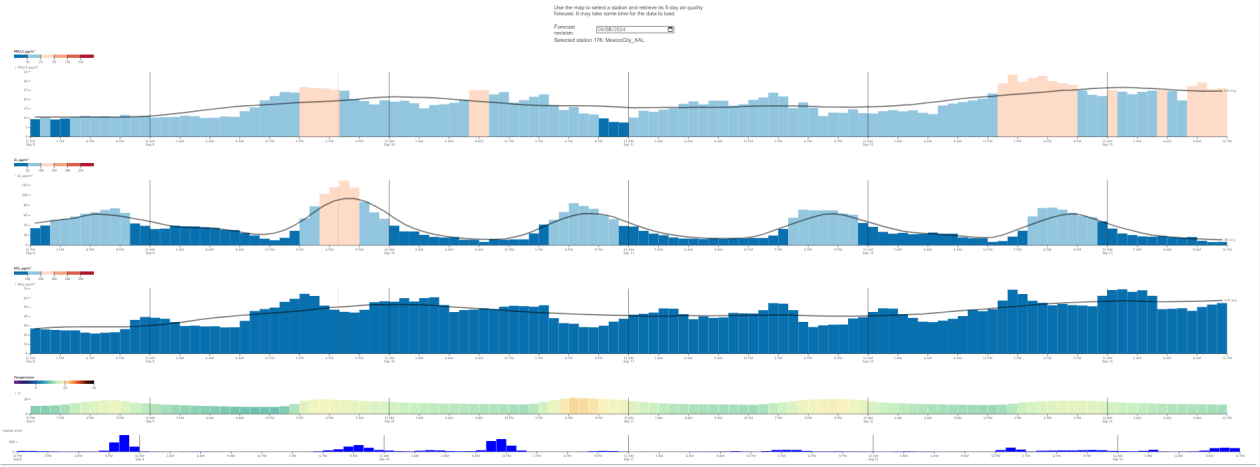

Early warning systems for extreme weather are critical tools for preparing people for dangerous conditions, as Guterres noted in his call to action on extreme heat. But access to information about air quality is also essential for navigating the spikes in pollution levels that accompany heat waves. Integrating air pollution forecasting into early warning systems is especially dire in low- and middle-income countries that often lack the data, capabilities and satellite modeling needed to generate their own air quality forecasts. WRI and the NASA Global Modelling and Assimilation Office have collaborated to give cities in lower-income countries access to air quality forecasts through a tool called CanAIRy Alert. Bias-corrected GEOS Composition Forecasts (GEOS-CF) are currently available for 121 sites in 21 cities around the world, helping decision-makers better predict increases in air pollution, identify solutions and prepare public health responses.

Integrated climate and clean air solutions

The impacts of air pollution and extreme heat are intertwined, so their solutions should also be connected. Reducing emissions — by mandating strict standards for industries, improving public transport and encouraging non-motorized transport, for example — can clean the air while helping curb the temperature increases associated with climate change. Ending dependency on fossil fuels and investing in renewable energy sources are also imperative and can help reduce both temperatures and air pollution levels.

In the short term, cities should develop emergency response plans to hazardous heat and air quality, which could include limiting cars allowed on the roads and shutting down high-polluting factories to temporarily reduce emissions during high pollution events. Cities can increase their longer-term resilience to both heat and air pollution through enhanced urban planning that could feature open ventilation corridors to more effectively disperse air pollution. They can also build green infrastructure like urban tree cover, which can interrupt the urban heat island effect by cooling cities while also absorbing air pollutants.

Building Momentum

Guterres’ call to action in response to the record-breaking July 2024 heat wave is a welcome, and essential, step forward. As part of this mobilization, countries around the world must also consider the role that air pollution is playing. The combination of extreme heat and poor air quality is especially harmful to human health and our ecosystems, and the world must take swift action on both.

A better understanding of the interplay between high temperatures and air pollution is critical for implementing immediate and long-term solutions to the problem. Deeper knowledge about the connection, and more widespread and equitable access to data and tools, can lead to more effective preparations. Solutions to this dual threat should also consider the susceptibilities and vulnerabilities of different populations, like disproportionate health impacts, illnesses and hospitalizations. The next step is building global momentum — and taking collective action to maintain it.

This article originally appeared on WRI’s Insights.

Beatriz Cardenas is Air Quality Director at WRI México.

Shazabe Akhtar is Air Quality Research Analyst at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.

Beth Elliott is Communications and Engagement Lead for Air Quality at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.

Nina Saaty contributed to this article.