A systematic, consistent, national-level dataset on India’s water bodies that could inform efforts to improve water management and increase resilience has been long awaited. The National Water Body Census 2023 is a crucial milestone in creating such a database. Undertaken by the Ministry of Jal Shakti, the water census surveyed and disaggregated 2.4 million water bodies.

This blog explores the census data related to urban water bodies, highlighting existing water challenges across Indian cities and ways to strengthen urban water resilience.

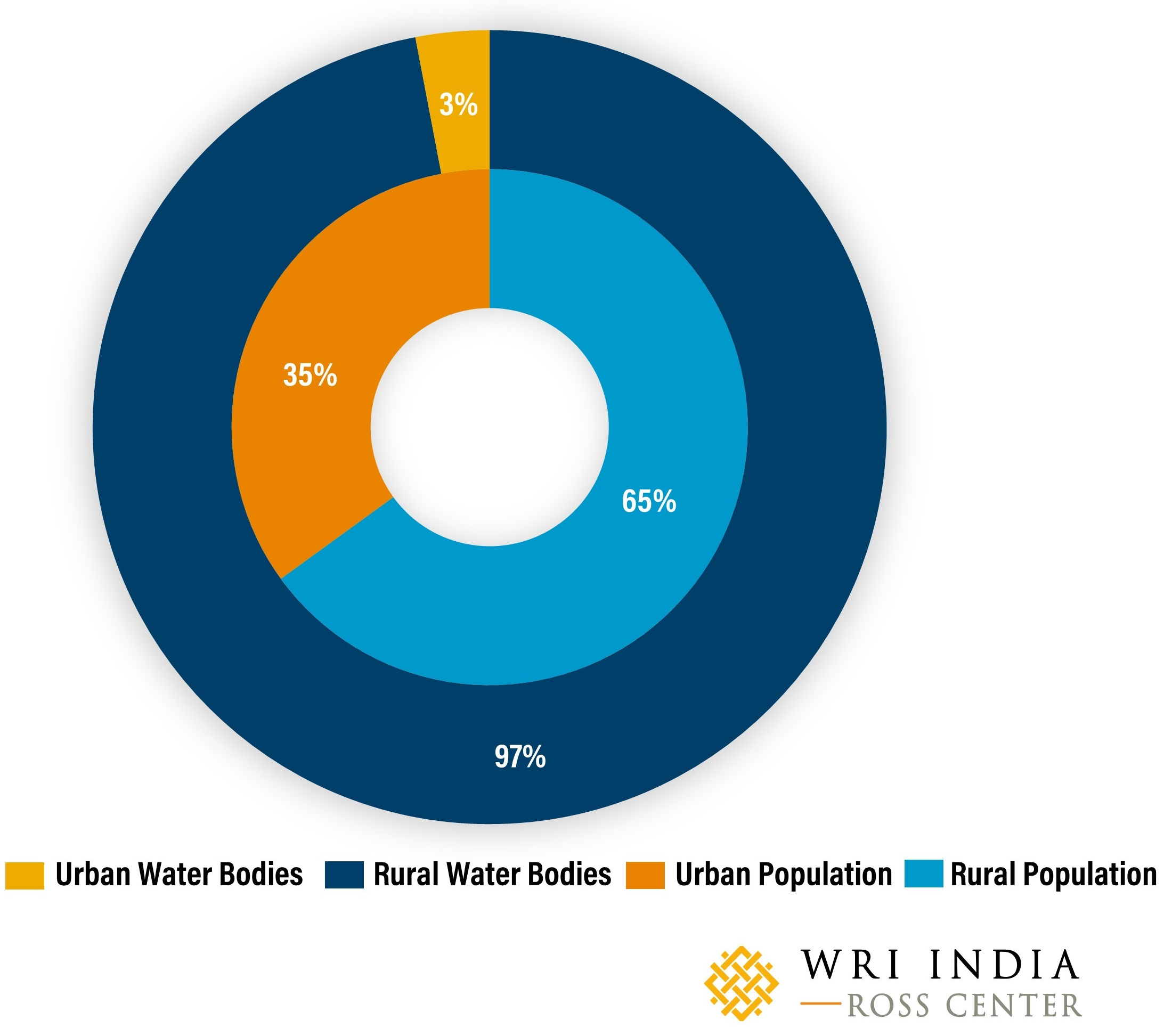

Currently, 35% of the Indian population resides in urban areas and by 2035 this percentage is projected to reach 43%. Rising urban populations and depletion of existing water resources, further exacerbated by climate change, impacts the availability of essential services, quality of life and the health of natural habitats and native biodiversity.

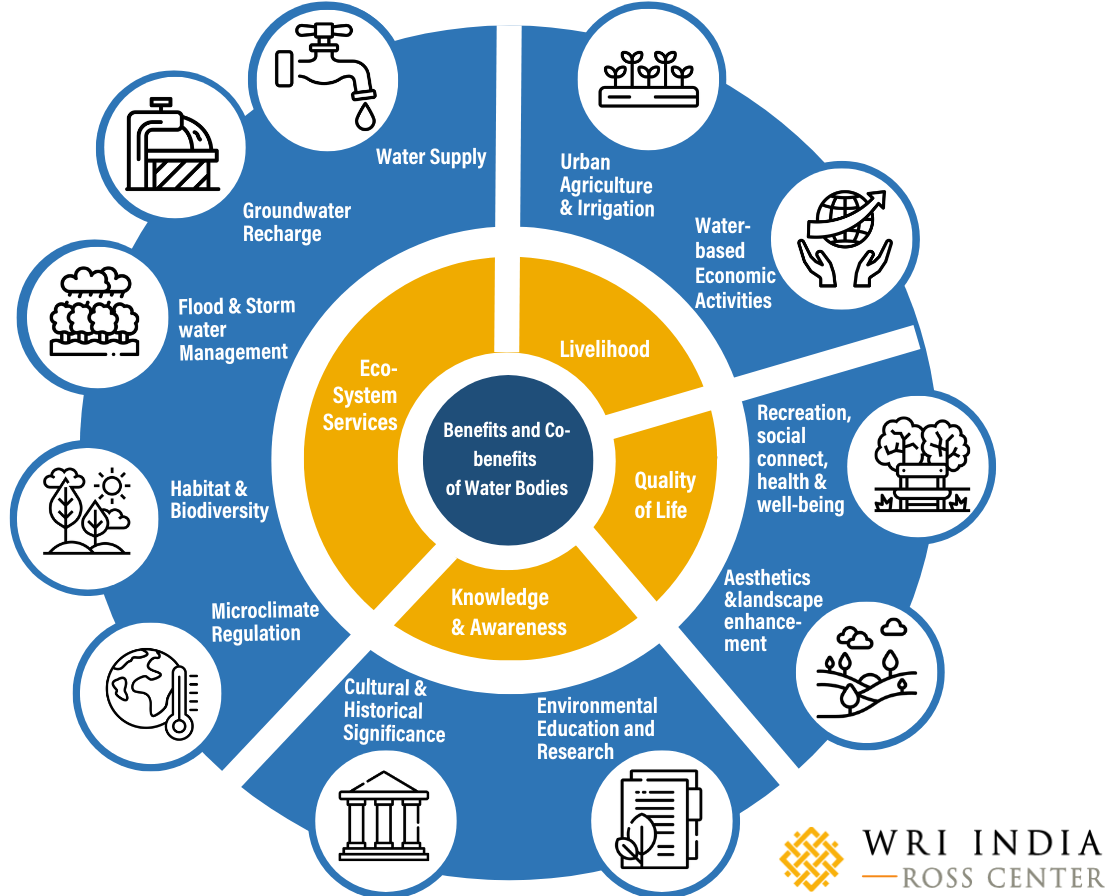

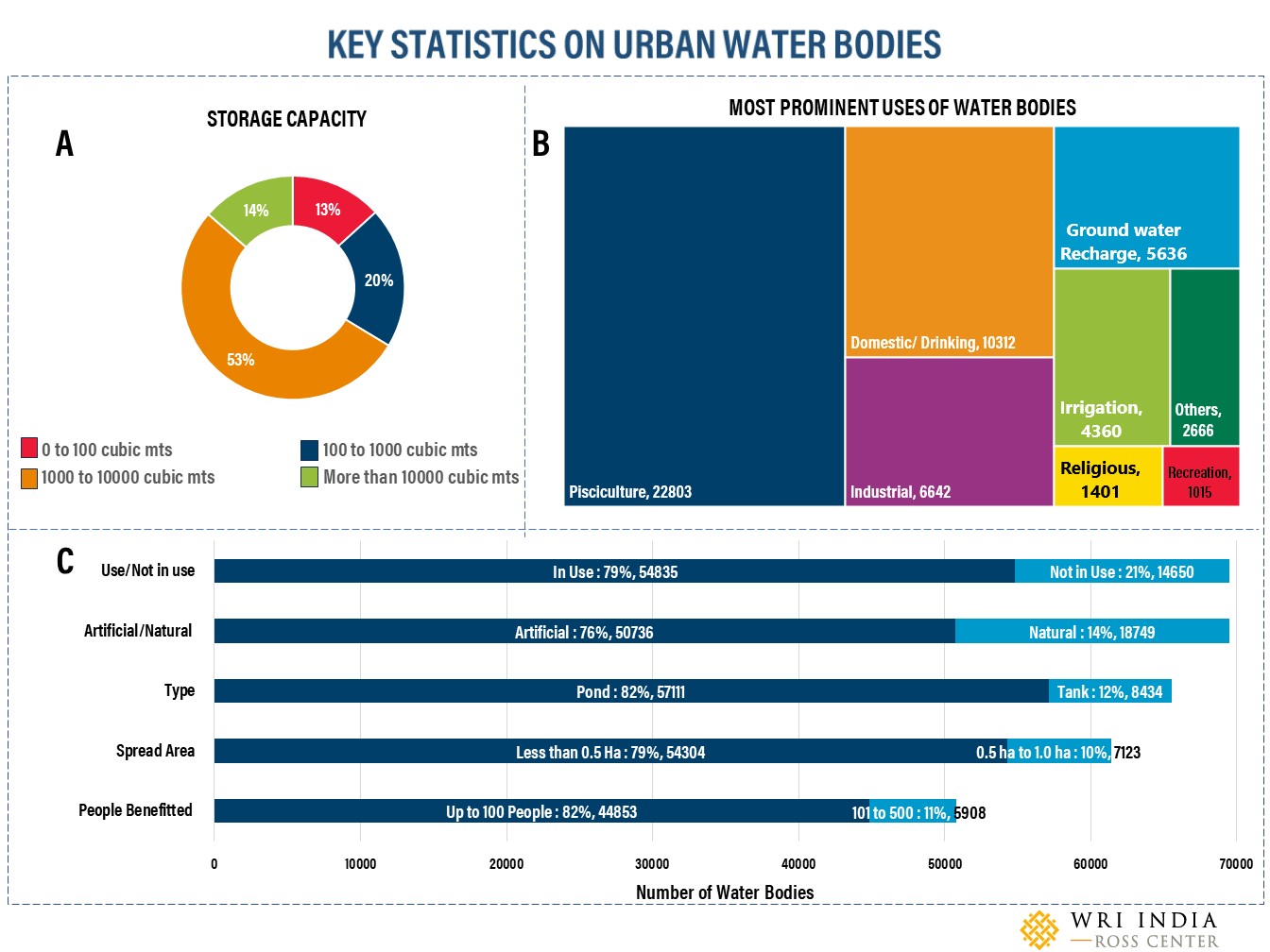

Surface water bodies such as ponds, tanks, lakes, reservoirs and percolation tanks play a significant role in mitigating both current and future water-stress incidents. They serve as storage reservoirs that can be accessed during water-scarce periods to recharge groundwater and facilitate flood control by absorbing stormwater run-off.

The census studies such water bodies by categorizing them based on storage capacity, uses and other aspects.

Diving Deeper into the Census

Although data collected has been helpful in illuminating the reality of water-stress in India, the census falls short of recognizing the co-benefits of urban water bodies beyond water storage, such as their role in microclimatic control, ecosystem services and biodiversity conservation. The data also shows inconsistencies in the number of water bodies reported in Karnataka and Himachal Pradesh and contradicts the findings from other reports and agencies. In Karnataka, the Census reported 27,000 water bodies (urban and rural), which does not match the findings of state nodal agencies.

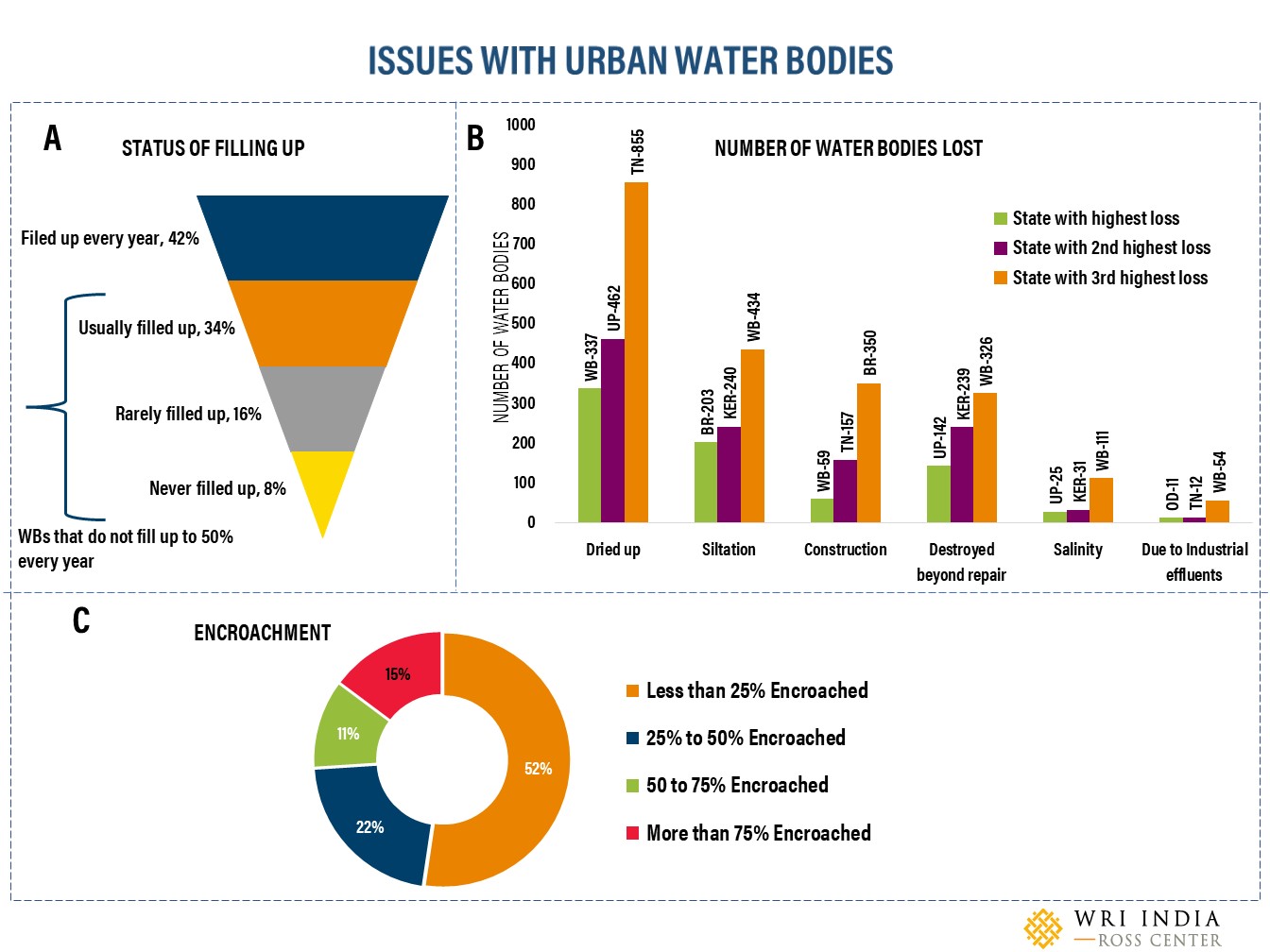

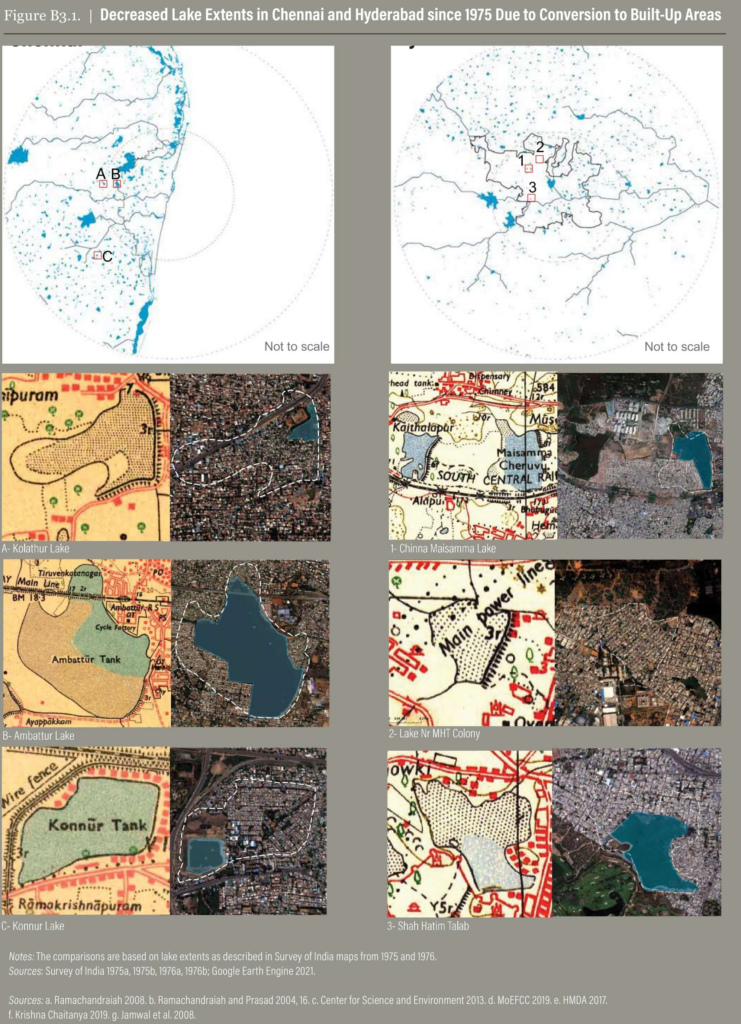

Furthermore, encroachment of water bodies in India’s urban regions has been reported in various primary and secondary documents and maps. WRI India’s publication, Urban Blue-Green Conundrum, and Interactive map explorer, also report significant encroachment of water bodies. For some of the states like Karnataka and West Bengal none of the urban water bodies report encroachment to any extent.

The census data is primarily aggregated and presented at a state level and classified into broader categories. It does not present detailed local-level information, nor does it touch upon the quality of urban water bodies.

Recommendations for Water Body Census 2.0

Consistent, transparent data with timely updates can help city leaders make informed decisions toward strengthening urban water resilience. Here are three key suggestions for India’s next Water Body Census:

- Include co-benefits. The next Water Body Census should recognize and include all co-benefits of urban water bodies to help cities properly value their preservation and maintenance.

- Enhance data quality and relevance. Prioritizing consistent, vetted and accurate data by utilizing advanced techniques like remote sensing and crowdsourcing, will improve data relevance, accuracy and cost-effectiveness. It also minimizes human errors in showcasing seasonal and time-series changes to water bodies and identifying climate change impacts on water bodies.

- Localize data and create accessible dashboards. Accessible information at the local, regional and state levels can be presented through dashboards that consolidate geospatial and other data from various institutions and databases. This can help inform decisions around prioritizing water-sensitive urban development.

While better data can effectively guide strategies to promote sustainable water management, connecting residents with local water bodies and bringing back traditional cultural practices can further improve their long-term usage and maintenance. Moreover, urban water bodies can act as powerful catalysts for behavior change by inspiring environmental consciousness, promoting community engagement and encouraging sustainable practices that benefit individuals as well as the broader ecosystem.

This article originally appeared on WRI-India.org.

Krishna Kumar is a Junior Associate for WRI India‘s Urban Water Resilience program.

Purnanjali Chandra is a Project Associate for WRI India‘s Urban Water Resilience program.

Vaibhav Shrivastava is a Senior GeoAnalytics Project Associate for WRI India‘s Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.