Traditional, car-centric transport planning has not only increased greenhouse gas emissions, but has also detrimentally impacted air quality, road injuries and fatalities, and traffic congestion. As the world faces the climate crisis and continues to face a growing global road safety crisis, a shift to sustainable transport is needed.

Attaining and sustaining high rates of walking and cycling — the lowest carbon modes of transport — are among the most powerful changes communities can make to achieve their sustainability, economic and social goals. Prioritizing pedestrians and cyclists over motor vehicles and ensuring safety of all road users is best achieved by investing in walking and cycling infrastructure and initiatives. Yet, walking and cycling, also known as active mobility, remain grossly underfunded, while car-centered planning and design continue to take the lead.

A recent paper from WRI, the World Bank and the Dutch Government sets out how investment in walking and cycling can be achieved to increase or sustain significant rates of active travel globally, and how investments can be improved.

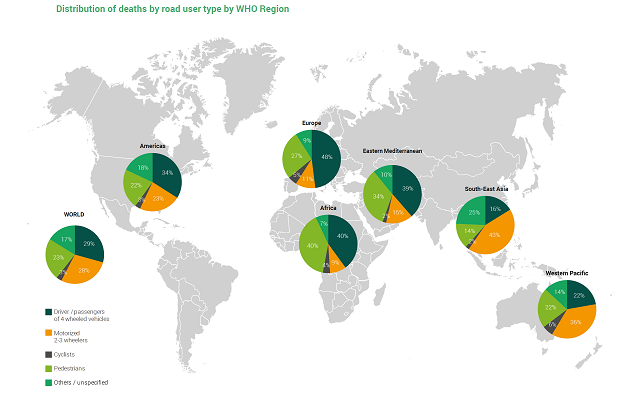

Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) that already have high levels of walking and cycling should especially take note: Each year approximately 1.25 million people are killed in road traffic crashes in these countries, which is around 90% of global road fatalities. Many of these fatalities are pedestrians and cyclists, due to a lack of safe infrastructure and speed management strategies. Investing in these interventions can help reduce these risks.

The Many Benefits of Walking and Cycling

Active mobility has immense untapped potential and when fostered through safe infrastructure, brings numerous economic, environmental, health and social benefits to the community. In urban areas, over 50% of trips are typically under 10-kilometers, distances that are easily walked or cycled. Yet cities and countries often overlook the critical role of walking and cycling in the transport system and the numerous benefits this can bring their communities, meaning walking and cycling gets left out of transport budgets and infrastructure projects.

First, high rates of active mobility lead to greater connectivity, reduced traffic congestion, more reliable travel times and increased public transit ridership. Cities in Southeast Asia lose 2 to 5% of their annual GDP to congestion, with Manila in the Philippines suffering the worst loss at $67 million per day. Improving walking and cycling infrastructure can help to lessen congestion and the monetary loss associated with it.

Second, active travel can help reduce emissions to achieve global targets. Cities contribute 70% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions and 21% of these come from urban transport alone. Shifting to walking and cycling can drastically reduce emissions and is the quickest and most efficient way to decarbonize transport. Compared to electric vehicles, cycling is 10 times more important for attaining net-zero cities.

Third, positive effects on public health are also abundant with safe walking and cycling infrastructure. For example, the World Health Organization found that scaling up sustainable mobility in Accra, Ghana, could save up to 5,500 premature deaths with improvements to air quality and an additional 33,000 lives from increased physical activity over a 35-year period — and a saving of $15 billion in health care costs.

Fourth, cities and towns have witnessed boosts to their economy upon improving pedestrian and cycling infrastructure, such as increased sales, commercial rent and job creation. One case study estimated that 11 to 14 jobs are created per $1 million invested in cycling and walking projects compared to the seven jobs created when investing in highways.

Finally, traveling by foot or bike even improves equity, social cohesion, perceptions of security and liveability. After Istanbul, Turkey, pedestrianized its peninsula, a survey revealed that 68% of pedestrian respondents felt more comfortable in the area. Many low-income populations also live with little transport access or unsafe and inconvenient routes to their destinations. Constructing safe active travel networks can improve access to opportunities and services for these disadvantaged groups. Ultimately, people’s physical, mental, social and economic health benefit from the ability to walk or bike in safe environments.

Methods for Investing and How it has Been Achieved

Finding the funds to support active mobility infrastructure is often a major obstacle for communities, despite walking and cycling infrastructure being the most cost-effective way for communities to serve the most residents and improve their transportation systems.

Methods for investing in walking and cycling vary widely, but there are some key ways funding can be achieved at the local, national, international and even private sector levels:

1. Cities and Towns Find Innovative Methods to Invest in Active Travel

The most common way local governments fund their active mobility projects is through general municipal funds, public works budgets or capital improvement programs. Towns and cities can also merge projects across departments to reduce costs and unlock further funds — such as installing bike lanes during pavement resurfacing.

A more advanced step that local governments can take is to develop active mobility strategies (sometimes termed non-motorized transport strategies), especially those that include dedicated funds or funding sources. In 2014 the city of Fortaleza, Brazil, adopted a strategic cycling infrastructure plan, totaling 524-kilometers. To fund the network, the city tapped into revenue from an online and app-based parking system. Annual bike counts conducted by the city have seen a 153% increase in the number of cyclists from 2012 to 2017 and the cycle network has grown 350% since 2013.

To overcome limited resources and tight budgets, local governments have also become creative and found other ways to source the needed funds. These sources can range from congestion charging to creating Business Improvement Districts to requiring developers to include sidewalks and bike lanes in their designs.

2. Countries Need to Integrate Active Mobility into Existing Transport Plans

At the national level, creating active mobility policies and plans is also the most effective way to ensure funds go toward walking and cycling infrastructure and are sustained over time.

Ireland, for example, has developed a comprehensive active travel investment program set to receive 20% of the annual transport budget. At €360 million per year, the country is investing €1 million a day in active mobility, a huge increase from the previous €12.64 million (less than 2% of the annual budget.) Notably, Ireland has also chosen to split the funds equally between walking and cycling, highlighting the need for walking and pedestrian infrastructure to be given greater weight.

Historically, nationally designated funds for active mobility have been lacking, but as the climate crisis looms and the COVID-19 pandemic persists, the importance of active mobility is increasingly being recognized. The funding that does exist is largely clustered in high-income countries located in Europe and North America, reflecting a distinct need for national governments elsewhere around the globe to prioritize active mobility in their budgets. For LMICs, a critical first step is to integrate walking and cycling into existing national transport plans or standards.

3. International Investment has Global Potential to Address Safety Deficits

Multilateral development banks (MDBs) have supported nations and cities across all regions of the world with policymaking and infrastructure development. Multilateral finance has an important role to play in advancing active mobility in LMICs given the considerable financial and institutional challenges these countries often face.

MDBs and international climate funds especially have the potential to address safety deficits in the global road network. Currently, over 85% of roads do not meet minimum walking and cycling safety requirements. Although most multilateral projects related to walking and cycling are to provide technical assistance, there are a few examples of active mobility infrastructure projects.

In 2009, the World Bank and the Global Environment Facility financed sustainable mobility projects in four Argentine cities. The investments financed 18-kilometers of bikeways, a public bike-sharing system and capacity building projects, as well as other public transport and urban planning activities. Although the reach of the project was modest, the replication potential is significant and should serve as an example of how climate funding can produce infrastructure that improves conditions for people who walk and cycle.

4. Private Sector and Public-private Partnerships Find Incentives in Investment

In addition to public and international funding, many private sources invest in active mobility infrastructure or programs. Public-private partnerships can be particularly powerful for financing active mobility and have been used to introduce bike-share systems in several large cities, such as London, Mexico City, New York and Paris.

Other private institutions may find that their missions are mirrored in the benefits brought by active mobility. Hospitals and health care systems, for example, have been known to contribute to physical infrastructure projects, especially those that provide access to their network for employees, visitors and patients alike.

Universities and colleges are also keen to improve accessibility for their students, faculty and staff through cycling networks. In 2020, an assessment by Decisio and the Dutch Cycling Embassy for Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú in Lima found that it would cost the university six times less to provide its employees with cycling facilities than to provide on-campus parking.

It’s Time to Improve Investments in Walking and Cycling

Active mobility has yet to become an institutional priority at the local, national or international level, where decisions about resources and financing opportunities are made.

The COVID-19 pandemic has seen massive global increases in people walking and cycling as they social distance and seek ways to move around their communities safely. Interventions, like pop-up bike lanes and pedestrianized streets, have grown during the pandemic and will play an important role in economic recovery as public transportation ridership remains low. Cities around the world should be careful not to lose this momentum for active travel by investing in walking and cycling infrastructure through various green economic recovery plans.

Now is the time to be bold and invest big in safe and convenient walking and cycling infrastructure to improve connectivity, protect pedestrians and cyclists, and reap the multitude of benefits that come with active travel. Reclaiming and redesigning roads and public space is necessary for walking and cycling to become safer and for a meaningful modal shift to occur — and none of this will be possible without significant investment.

This article originally appeared on WRI’s Insights.

Hannah Ohlund is an Urban Mobility Research Analyst at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.

Siba El-Samra is an Urban Mobility Associate for Health and Road Safety at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.

Claudia Adriazola-Steil is Acting Director of Urban Mobility and Director of Health and Road Safety at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.

Giovanni Zayas is an Active Mobility Consultant at the World Bank.

Felipe Targa is a Senior Urban Transport Specialist at the World Bank.