The latest UN climate conference, COP27 in Sharm el Sheikh, Egypt, was a significant one for cities in many respects. Delegates established a new fund to help vulnerable countries deal with loss and damages from climate impacts, and some of the worst losses from climate disasters and extreme weather events will be seen in urban areas in these vulnerable countries, particularly in communities under-served by basic infrastructure and services. COP27 also hosted the first “urban ministerial,” a high-level event that raised the profile of city leaders and concerns amidst a forum of national governments.

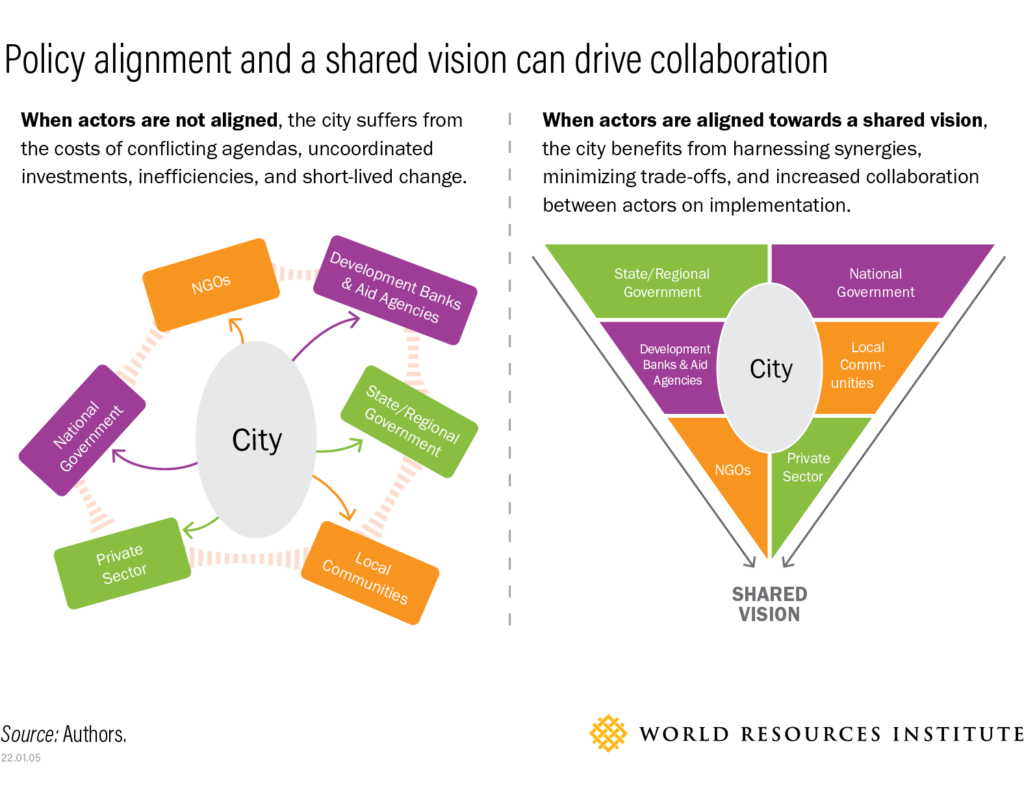

But neither cities nor national governments can mitigate or adapt to climate change alone; they need each other to succeed – and indeed many more stakeholders, including community groups, businesses and research organizations. Multistakeholder strategies and partnerships are essential to driving transformative climate action in cities.

To demonstrate how different stakeholders can center equity within plans for low-carbon and climate resilient cities, we launched a new set of recommended actions by actor at COP27 at an event featuring a diverse set of urban changemakers working in India, Mexico, South Africa and globally. The recommended actions by actor are derived from the research of dozens of experts in our flagship World Resources Report series, Towards a More Equal City, and the event comprised a lively discussion facilitated by WRI President and CEO Ani Dasgupta.

The actions identified in this roadmap document show how different stakeholders can enable crucial shifts needed in the areas of urban infrastructure design and delivery, service provision, data collection, urban employment, finance, land management and governance. These represent the seven transformations for more equitable and sustainable cities that emerged as a synthesis of the World Resources Report research. Now, we identify specific actions for city government and urban sector specialists, national government and civil society, including nongovernmental organizations, experts and researchers, private sector and the international community, including development finance institutions under each of these transformations.

More than 1.2 billion people globally — or one in three urban residents — are under-served daily by core urban services such as good-quality housing, transport, water, sanitation and energy. The number expands to two in three urban residents in low-income countries, many of which are urbanizing rapidly in the face of increasing vulnerability to climate disasters. Our evidence shows that bridging the “urban services divide,” the gap between those who have access to core urban services and those who do not, can bring cascading benefits to the entire city and unleash transformative change that is good for both people and the planet. But success depends in large part on aligning the visions and activities of a broad set of actors that influence cities, from national government to the grassroots level.

Here are four examples explored at our COP27 launch event that highlight the importance of multistakeholder strategies and partnerships for closing the urban services divide while addressing mitigation and adaptation to climate change in cities. These examples from practice reflect one or more of the seven transformations from the World Resources Report research:

City governments and mayors working in collaboration with each other at the regional scale and with higher levels of government can boost the availability of resources.

Cities need cooperation and fiscal and technical support from national and state governments and the participation of civil society to build lasting support for transformative change. For example, Monterrey, Mexico, is moving towards carbon neutrality by 2050 to mitigate the climate crisis.

The Monterrey Urban Park System and Sustainable Corridors is a project aimed at connecting more residents to green spaces and improving air quality and urban mobility, explained Mayor Luis Donaldo Colosio. While the project began at the city level, Monterrey scaled it to a larger, metropolitan-scale green corridor by collaborating with other mayors in the region and the state government. Since the project serves multiple municipalities, the state government was willing to pay for 50% of the project.

“I’m a city government, I don’t have sovereign guarantees for big banking institutions that can bankroll my green infrastructure project,” said Colosio. “But as a collaboration of mayors in the region, we have designed a scheme where we share resources. We don’t have many resources to go around, but the state government has stepped in to help many of our green infrastructure projects.”

Community participation in making and implementing policy is essential for creating a sustained, shared vision.

Civil society can offer valuable perspectives and by welcoming and empowering these groups, city officials can catalyze broader political support for policies and programs. One example is Mahila Housing SEWA Trust (MHT)’s work with communities in India who endure considerable income loss during the heat season as productivity declines.

The city of Ahmedabad, India, had a heat action plan, but it focused mostly on early warning systems and hospital readiness. MHT prepared and empowered women in communities to engage with city government about adding a cooling and greening component to the heat action plan. Together, they made the plan more holistic and led to the creation of heat-reducing ceramic mosaic roofs in 17,000 new public homes. Another example is Slum Dweller International’s work bringing the concerns of those living in informal communities to government officials, starting with collecting and sharing data through the Know Your City campaign.

“We are starting to have climate action plans, but a lot of urban development plans are still working separately from the climate plans,” said MHT Director Bijal Brahmbhatt. “People really don’t understand this intersection. We need to get this understanding out of the research.”

Combining national government finance with both traditional and innovative local financing can support vital investments in urban services.

The need for financing to provide both basic services and to deal with climate change increases every day. While investments in core services and infrastructure can often pay for themselves many times over, cities can rarely afford to finance large infrastructure projects on their own.

Frannie Leautier, CEO of SouthBridge Investment, explained that financing for urban services and climate action must happen at four levels together: self-provision or the last-mile (i.e. the household scale), the neighborhood scale, the city scale, and finally the regional scale, linking several municipalities together. National governments collect almost three-quarters of total public revenues worldwide, so they are uniquely positioned to finance these types of projects.

Kenya provides an interesting example of multistakeholder collaboration for financing. The national government pulled together all municipalities and aggregated their assets, which created an opportunity to raise a bond at the national level for municipalities. Then municipalities used the bond to provide urban services, such as piped water, garbage collection and large-scale electricity generation.

Citizen participation drives transformative change when people unite under a shared vision.

In 2018, Cape Town, South Africa, experienced a water crisis so severe it was on the verge of being without any water, “Day Zero,” as it was called. Communications were sent out to convince people to reduce their water consumption. In informal settlements, water became free and without any restriction, but for the wealthier, water became five or six times more expensive. They were forced to decrease consumption or pay unsustainable bills, explained Carlos Lopes, professor at the Mandela School of Public Governance, the University of Cape Town.

“The idea of Day Zero, where there would be no more water, was so graphic that people reduced their water consumption and Day Zero never arrived,” said Lopes. “We now have a city of 5 million people that is consuming half of the water it used to consume. You can see that it is possible to have bottom-up approaches.”

—

As our exploration of what leads to transformative change in cities shows, everyone has a role to play. Some actors necessarily work top-down but may not be clued into community needs, while others may work in bottom-up ways but lack the capacity to connect initiatives and resources to achieve scale. These bottom-up and top-down efforts need to be aligned and mutually supportive. Towards a More Equal City includes multiple in-depth city case studies of transformative change in action.

Despite the new loss and damage fund and other steps at COP27 like the initiation of an urban ministerial to draw attention to the role of cities, there were no significant steps taken to commit to cut emissions further, or sooner, which is vital to avoid more severe climate impacts and stay below 1.5 degrees. But climate commitments are happening at all levels and by a range of stakeholders.

With 2.5 billion more people expected to be added to cities by 2050, and with growing gaps in access to urban services, there is a huge opportunity to meet the climate challenge and create more equitable cities at the same time.

Maeve Weston is a Research and Engagement Specialist at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.