Mobility startups can make paratransit accessible, affordable and more integrated into the transport framework. Photo by Fred Inklaar/Flickr

The fundamentals of urban mobility are changing rapidly. Apps like Uber and Lyft are becoming ubiquitous around the world and new modes like electric and shared bicycles and scooters are on the rise. The conversation is increasingly trending toward mobility as a service, in which access to vehicles largely replaces ownership. The end results, ideally, are less street space devoted to motorized private transport, more affordable travel and greater access for all.

Just as these changes have transformed the mobility landscape in cities around the world, African cities are also seeing an emergence of new mobility startups. These new startups have the potential to shake up urban mobility as it stands.

Today, African public transport is largely limited to privately owned minibus taxis, or paratransit, sometimes referred to as informal transit depending on its characteristics and legal status. Though cities are investing in new infrastructure for bus rapid transit (BRT) and private vehicles, paratransit remains the primary way residents connect to employment, health care and education ‒ more so than many policymakers care to admit.

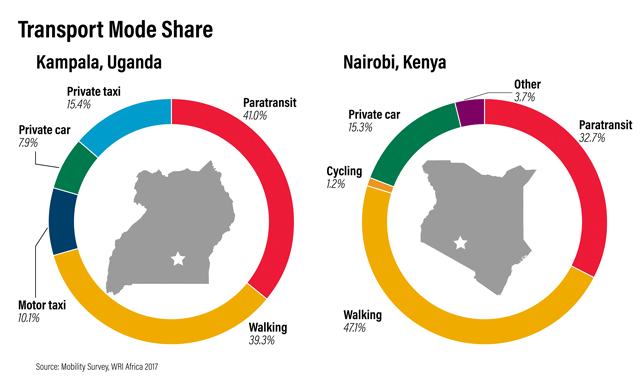

But while popular, paratransit is unaffordable for most lower-income residents. In Kampala, Uganda, for instance, fares comprise up to 25% of median household expenditures (in the United States, public transit costs 1-5% of median household incomes). As a result, walking is the only affordable option for the large majority of men and women living in slums. And when they do walk, it is often on dangerous roads with minimal pedestrian infrastructure. Africa has the highest rate of road fatalities of any region in the world.

In major African cities, like Kampala and Nairobi, walking and paratransit are the dominant forms of transportation. Mobility profile data is collected via survey with city officials. Graphic courtesy of Travis Fried/WRI.

For those who do take public transit, there is room for improvement, particularly in how residents connect to the network. For instance, in cities where BRT is being built out, there is often little thought as to how residents will access the system, if they do not live or work near a station. Emerging tech startups could help fill this gap. Motorcycle ride-hailing services and bike-sharing could facilitate first- and last-mile connectivity, for example, and cashless payments could mean one fare and easier transfers between paratransit and BRT operators.

But whether solutions see broader improvements in accessibility for all residents hinges on the ability of cities to make the most of their relationship with these new private enterprises.

Mobility Startups, Data and Innovation on the Rise

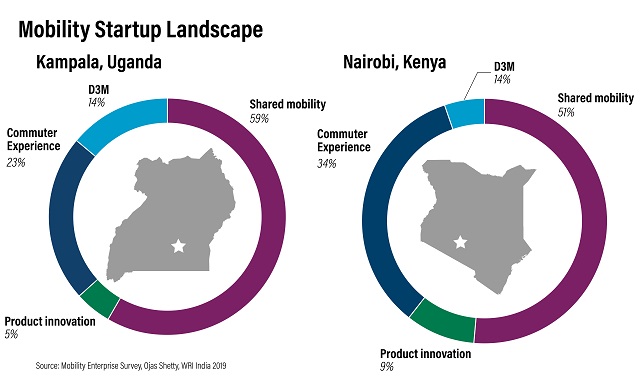

WRI Ross Center conducted an exploratory review of tech-enabled mobility startups in Africa, drawing on open online databases and interviews with local enterprises. We discovered 180 mobility-related startups launched across Africa between 2010 and 2019. The most common type of company (57%) was shared mobility, which includes ride-hailing and ride-sharing services, like Uber and Bolt (formerly Taxify), as well as app-based motorcycle services, like SafeBoda. This number has dramatically increased from 34% two years ago, as reported in our 2017 survey.

In addition to shared mobility services, we surveyed startups in three other mobility tech categories, based on our prior global research:

- Product innovation: Services that enhance transportation technology and improve performance, like electric vehicles. For instance, the Ugandan government and local Makerere University invested $39.8 million in Kiira Motors Corporation. Kiira aims to manufacture solar buses, electric sedans and hatchbacks ‒ the first manufacturer of its kind in the country.

- Commuter experience: Services that improve the mobility experience for users with information sharing, like mobile ticketing and trip navigation. There are also initiatives to provide cashless, tap-and-go payment systems for conventional buses, like in Kigali, Rwanda. Cities with extensive paratransit networks have fared less well with cashless payment to date.

- Data-driven decision-making (D3M): Services that provide insight for better transport planning, like traffic flow management, freight logistics and fleet tracking. Bwala, for instance, is based in Nairobi and Kampala and uses app-based tools to help source auto-parts and repair services for freight fleets.

Bridging the Public and Private Sectors

There is a role for entrepreneurs and startups, as well as existing paratransit operators, in creating better transportation in African cities. But policymakers need to do their part to create an ecosystem that allows for such innovation to occur. While this is an emerging area, as with most innovation-driven change, there are some factors cities should consider to create the maximum public good. Most of these involve public-private collaborations that draw on the strengths of both public sector agencies and private operators.

Information to Improve User Experience

Information systems that give passengers data about arrival times, costs, routes, and more are essential to understand and navigate a city’s transit system. Riders often lack this basic information in African cities, especially where paratransit is dominant. Creating both a static and digital map of a city’s transit network not only allows riders to plan their trips in apps like Google Maps and Transit, but it’s a necessary step to designing integrated systems. The first step cities and universities can take to create a thriving mobility tech ecosystem is mapping transit routes and stops themselves.

Data-driven Decision-making

Data is also required to more strategically plan and integrate routes and fares across modes. In South Africa, companies like GoMetroPro and WhereIsMyTransport are using data from private and public transit operators to locate overlapping and redundant routes and identify opportunities where minibuses can feed into higher-capacity services, like BRT. Optimizing or aggregating transit routes and stops means cost-savings for operators, a more seamless experience for riders and fewer vehicles on the road.

Physical Integration

Transit riders need safe and convenient access to and from important station areas, like taxi stands and BRT stops. Connecting ride- and bicycle-sharing to transit is an exciting, new frontier for African cities. Bhopal, India, for example, attributes the success of their new bike-sharing system to its integration with the city’s BRT corridor. Efficient and safe design can amplify the benefits of new technology and allow new services to flourish through increased ridership. This means improving infrastructure for bicyclists and pedestrians through traffic-calming, speed management and complete streets practices to enhance last-mile access to hubs for shared mobility services.

Institutions and Governance

Building capacity at the institutional level can often lead to improved relationships between the private and public sectors. Planners who are familiar with data standards and their uses can more effectively communicate with startups, transit operators and other policymakers. The Inter-American Development Bank’s City LAB is one example of a forum that builds capacity across sectors by connecting students, entrepreneurs and city officials in hackathons, “ideathons” and “Impact Hubs.” A similar model could foster more tech-enabled solutions across African cities.

—

While tech isn’t a cure-all for Africa’s transport woes, small projects have shown the potential of up-and-coming tech entrepreneurs and innovative public-private partnerships to bring new solutions to old problems. More reliable service, clearer routes, multimodal integration, shorter travel times, more affordable fares, and less congestion seem within reach. Through effective partnerships, these new services could connect millions of Africa’s current and future transit riders with greater opportunities.

Ben Welle is Director for Integrated Transport and Innovation at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.

Travis Fried is a Research Analyst for Urban Mobility at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.