Urban freight vehicles constitute less than 10% of vehicles on the road in most cities, but they account for a disproportionate amount of transport-related CO2 emissions and pollutants. According to the Beijing Transport Institute, freight in Beijing accounts for around 20% of transport-related CO2 emissions and more than 40% and 30% of toxic NOx and particulate matter emissions, respectively. As cities around the world look to transition to zero-emission transport systems for cleaner air and to prevent climate change, the short daily mileage and outsized impact of urban freight vehicles make them ideal for electrification.

A key way to incentivize electrification of urban freight vehicles is through zero-emission zones, areas that either strictly regulate or ban entirely fossil fuel-powered vehicles. Zero-emission zones that target specific classes of vehicles like freight have emerged as one of the more technologically and politically viable options in the near term for many cities. In the Netherlands, about 30 cities have set timelines for introducing zero-emission freight zones by 2025, and the 35 cities joining the C40 Green and Healthy Streets Declaration have committed to phasing in zero-emission freight zones by 2030.

In China, Shenzhen has had zero-emission freight zones since 2018. They have proven effective at accelerating the adoption of zero-emission freight vehicles, incentivizing their use by logistic service providers and production by vehicle manufacturers. The zones have also incentivized logistics service providers to consolidate deliveries and improve efficiency.

But Shenzhen has faced plenty of obstacles. Compared to the transition to zero-emission buses, already complex, the switch to zero-emission freight vehicles can be even more so. The high cost of electric freight vehicles can erode profits for logistic service providers and increase supply chain costs, which are already high. The urban delivery market is also fragmented and characterized by small logistic service providers. In response to these challenges, Shenzhen has relied heavily on incentive and exemption schemes for companies that face difficulties with vehicle replacement.

In a new guide by the Transport Decarbonization Alliance, C40 and POLIS on implementing zero-emission freight zones, WRI contributed a section on Shenzhen’s experience, highlighting what has worked and what hasn’t.

Starting Small and Engaging All Stakeholders

Shenzhen was the first city globally to introduce zero-emission freight zones. Established in 2018, it’s 10 “green logistic zones,” as they are known locally, grant all-day free access to electric freight vehicles with gross vehicle weights under 4.5 tonnes, while banning fossil fuel freight vehicles entirely.

Partly spurred by the zero-emission zone policy and partly by Shenzhen’s generous subsidies for vehicle electrification in general, by the end of 2019 the city had more than 70,000 battery-electric freight vehicles in operation, including vans, trucks and waste collection vehicles. The total number of electric freight vehicles even surpassed that of electric buses and taxis, becoming the largest operational electric fleet in the city.

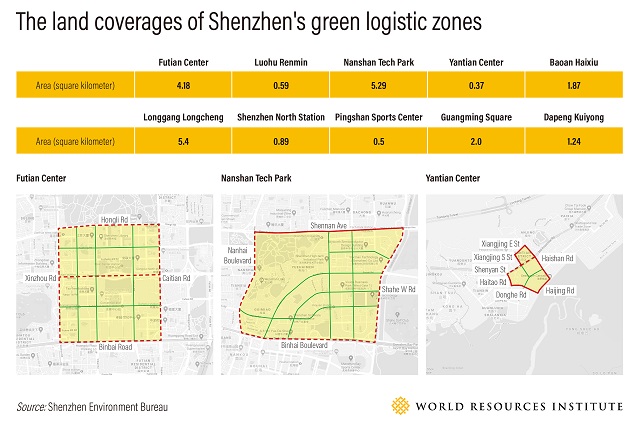

Instead of a single large zone, Shenzhen started with multiple small zones.The total land coverage of the zones is just 22 square kilometers, 1.1% of Shenzhen’s land area. The size of each zone spans from 0.4 to 5.4 square kilometers.

But the zones have had an outsized impact. The city government required each district to have at least one green logistic zone and used hot-spot modeling for pollutants and CO2 concentrations to identify best locations. The city also held extensive consultations engaging local retailers, property owners and logistic service providers, leading to the co-creation of zone territories and exemption rules.

These rules stipulated that zones should be small, with the possibility of future expansion; encompass major business centers and large residential neighborhoods affected by air pollution; and be bound by (but exclude) major roads to ease enforcement and provide alternative routes for through traffic. The rules also exempted certain vehicle classes that were extremely difficult to electrify, like refrigerated vehicles and heavy-duty tractors.

Financial Incentives and Vehicle Leasing

Shenzhen’s successful introduction of zero-emission freight zones largely hinges on its financial incentives and vehicle leasing schemes. Both measures have been critical, particularly for small logistics service providers, in overcoming cost barriers and shifting risk.

Before introducing green logistic zones, Shenzhen implemented ample financial incentives to make zero-emission freight vehicles cost-competitive. In addition to tremendous vehicle purchase subsidies, Shenzhen is the first Chinese city to provide operational subsidies for electric freight vehicles, more than covering vehicles’ charging costs. Electric freight vehicles also enjoy one hour of free curb-side parking.

Furthermore, instead of owning the electric vehicles, many companies in Shenzhen lease them from a third party, which saves their upfront investments and shifts risk to the leasers. Some leasers even provide added service, including combining small shipments from multiple companies into larger loads and using an information system to identify new demands.

Voluntary Schemes

However, many cities do not have Shenzhen’s luxury to subsidize the purchase and operation of zero-emission freight vehicles. When Shenzhen introduced its green logistic zones, it had already built up a critical mass of electric freight vehicles – a fifth of its total logistic vehicle fleet – through purchase and operation subsidies.

In the absence of generous government subsidy schemes, some cities are starting with voluntary schemes for logistics service providers and communities before launching mandatory zero-emissions zones. Rotterdam, looking to phase in a zone by 2025, is identifying “champion” companies for each delivery segment to demonstrate the possibilities for running a zero-emission fleet. In Los Angeles, local authorities have called for community proposals for small pilots areas, and a 1 square-mile zone was proposed by the city of Santa Monica to cover its key commercial district.

Avoiding Emissions Leakage

Another lesson from Shenzhen is the need to avoid emissions “leakage” from the zones. For example, a large zone lacking diversion routes can detour through traffic, causing longer routes and thereby actually increasing emissions. Weak enforcement can also result in illegal use of passenger cars for freight. So it is imperative that zero-emission freight zones are well-designed and strongly enforced if they are to help cities deliver clean air and emissions reduction goals.

With technological advancements in vehicle electrification, the urban freight sector faces unprecedented opportunities to curb its carbon footprint. Shenzhen shows zero-emission zones can play a key role in building momentum for accelerating freight vehicle electrification. Despite implementation challenges, cities can successfully phase in these zones through good design, supportive incentives, strong enforcement and quick-wins from voluntary schemes.

Lulu Xue is a Research Associate for WRI China Ross Center, where she supports sustainable transport efforts in Qingdao and Chengdu.