A man rides a Lime scooter down the streets of Austin, Texas, where the CDC recently conducted a study on electric scooter safety. Photo by James Cage/Flickr

Electric scooters are the latest “new mobility” tech to disrupt the transportation sector. Chances are you’ve seen someone passing by on one these small but nimble two-wheelers in a city near you. Following the explosive growth of bike-sharing and ride-hailing, scooters reached 38.5 million U.S. trips in 2018.

Scooters provide many of the same benefits as bike-sharing to riders—they offer quick and fun travel for short distances—while being even less intimidating to newbies. Like shared bikes, scooters have the potential to provide significant benefits to cities.

Early data suggests most scooter trips are between one and two miles long. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, if U.S. drivers chose to walk or bike instead of driving for half of all car trips shorter than a mile, it would save 2 million metric tons of CO2 emissions and provide about $900 million in fuel costs and maintenance savings. Scooters, like bikes, help with the “last-mile” problem—connecting parts of the city to public transport that were previously beyond reach—and expand access for residents who live in areas underserviced by public transit.

Some, however, have raised concerns about scooters’ safety, given their small size, lower center of gravity than bikes, relatively high speeds, some cases of scooters breaking unexpectedly and exposure to conflicts with vehicles or pedestrians.

Recent studies in the United States found that riding a scooter does carry some risks. However, they generally indicate that scooters are no more dangerous in terms of risk of serious injury or death than other modes of transport.

While more data is needed to fully understand relative risks across modes, we do know cities are becoming deadlier for all non-motorized users—that cars are hitting and killing pedestrians, cyclists and others at unacceptable rates. The arrival of scooters only lends more urgency to the effort to make it safer for people to move around cities without relying on cars.

Evidence from 4 Recent Studies

Scooters are a new phenomenon, and there isn’t yet a great deal of data available across cities. However, a few studies look at emerging scooter crash data in U.S. cities. We discuss the first, a CDC study released yesterday, at the greatest length, but also examine three more studies for context.

Austin, Texas

The Centers for Disease Control and the city of Austin, Texas, recently released an epidemiological study looking at scooter-related injuries over a three-month period in the fall of 2018. The study looked at multiple injury and demographic variables of 190 injured riders, of which almost half were considered seriously injured and 15% experienced a traumatic brain injury. The sample of scooter riders studied yielded an injury rate of 20 per 100,000 rides, meaning that a person taking four scooter trips a day could expect to be injured once every 3.5 years.

Fifty-five percent of riders were injured on the street, 33% on the sidewalk and 12% in other locations. The study found that 16% of incidents involved motorized vehicles, whether colliding with them or swerving to avoid a collision. Another 17% involved a curb, an object or a manhole.

The study concluded that most of the head injuries may have been preventable (only one of the riders who suffered a head injury was wearing a helmet) and proposes two next steps: Strengthening injury surveillance related to emerging vehicles like scooters, and increasing the frequency and methods of educational messages on safe riding, emphasizing helmet wearing and maintaining safe speeds.

However, there are other ways to interpret the results. One factor that may have contributed to high injury rates is the number of novice riders. Over 60% of the interviewed riders had made fewer than 10 trips on a scooter. More than 30% of those injured were first time riders.

Also, given that 55% of riders were injured on the road, and 50% of interviewed riders believed that pavement surface conditions led to their injuries, it would be useful to conduct analysis of road design, quality and maintenance. It would be interesting, for example, to analyze the relationship between injury locations and infrastructure for riders, such as bike lanes and other design features. A quick visualization of injuries reported in the study in downtown areas overlaid with the city of Austin’s own database of “high comfort” bike infrastructure is a starting point. Most injuries occurred away from protected infrastructure.

Comparing injury rates of scooters and other modes throughout the study period (normalized by trips taken or hours ridden) might have also shed some light on whether roads in the city pose a serious threat to all vulnerable users, or whether scooters have unique safety needs.

Los Angeles, Calif.

Another recent study looks at 249 patients with injuries associated with electric scooter use in two emergency departments of a UCLA medical center in southern California. Within a one-year period, 32% of these scooter-injury patients had fractures, 40% had head injuries, and 28% had soft-tissue injuries. Only 4% of patients were wearing a helmet at the time of their injury, but most patients (94%) were discharged home from the emergency room. Only 2 of 15 admitted patients had severe injuries.

This study is particularly interesting because it captured how riders were injured. Eighty percent fell off their scooters, 11% collided with an object and 9% were hit by a moving vehicle or object. The study doesn’t say, but it would be interesting to correlate how riders were injured with the severity of the injury.

Portland, Ore.

As part of the evaluation of a 120-day pilot program for scooters, Portland looked at a combination of qualitative and quantitative data, including trip data provided by scooter companies, emergency visits and a citywide representative poll.

Findings include:

- Most scooter-related injuries were minor.

- Scooter-related injuries accounted for 5% of total crash injury visits.

- Of these injuries, 84% were the result of an individual falling off a scooter. 13% resulted from scooter collision with a car.

- Streets with bike lanes saw the highest scooter usage.

- People rode on the sidewalk less when the road had low speed limits or protected bike lanes, demonstrating the importance of protected infrastructure and safer vehicle speeds to minimizing conflict between scooters and pedestrians and cars.

Bird

Scooter company Bird also recently published a study on scooter safety, which concluded that scooters and bicycles share similar risks.

Bikes produce 59 emergency department visits per 1 million miles cycled, according to a 2017 study in high-income countries; Bird reported an injury rate of 38 injuries per 1 million miles for scooters (based on injuries reported directly to Bird by riders). The study also found an association between cities with higher “People for Bikes” safety scores and fewer Bird injuries—with the upshot that making cyclists safer makes scooter riders safer, too.

According to a user survey asking what would make riders feel safer, most respondents want protected bike lanes, smoother pavement, wider bike lanes and designated scooter parking.

The Hidden Factor: Road Design

These studies might provide insights on potential scooter design pitfalls or riding at unsafe speeds, which are important safety elements. However, as scooter use grows, city leaders should consider a risk factor external to riders’ control: the way our roads are designed.

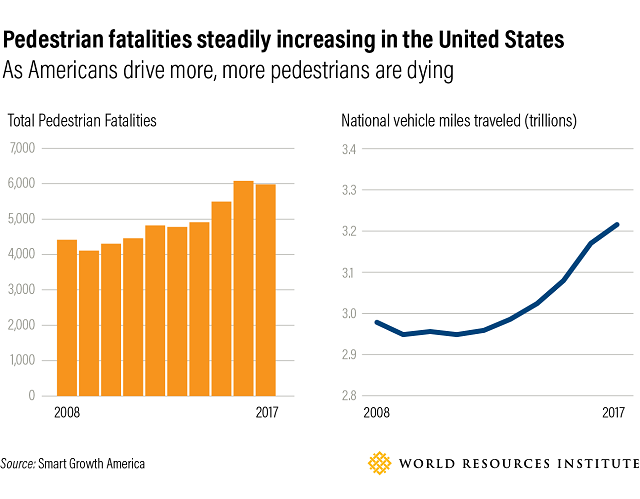

Over the last decade, the number of people struck and killed while walking increased by 35%, while vehicle miles traveled grew steadily. Drivers killed more pedestrians in the United States in 2016 and 2017 than any other year since 1990, and, globally, the numbers are also getting worse.

The current, car-centric design of our roads makes other modes of transport—most commonly cycling, scootering and walking—more vulnerable to collisions with cars. These kinds of unequal collisions are much deadlier than collisions between people engaged in the various modes of micromobility and “active” transport.

What can cities do to make their roads safer for scooters and other active modes of transport? Here are some recommendations from WRI’s work:

- Make roads safe by design by building protected bike lanes (which can also be used by scooters), redesigning intersections, and implementing traffic calming measures and urban design elements that can save lives like speed humps, chicanes, raised pedestrian crossings and improved street surfaces. Cities can scale these types of interventions through “complete streets” and Vision Zero

- Manage speeds: Lowering and enforcing speed limits from 50 to 30 kilometers per hour in busy urban areas can reduce the likelihood of pedestrian or cyclist fatalities from 85 to 30%. Narrower lanes, wider sidewalks, raised pedestrian crossings and curb extensions also all encourage safer speeds.

WRI is working in this space to make these types of transformations happen, via its Health and Road Safety team. WRI is also a member of NUMO, the New Urban Mobility alliance, which is studying the effect of micromobility services on cities in multiple ways.

Whether scooters help transform cities for the better, enabling more low-cost, low-carbon transport options for more people, will depend on city officials and scooter companies working together towards achieving that goal. For example, the public sector can push for policies that enable the benefits of scooter programs while preventing safety risks. The evidence suggests protected, high quality bike lanes can protect scooter users. Companies can also do their part by sharing data with cities (many have pledged to do so already, through the Shared Mobility Principles) and even helping cities develop or test needed infrastructure that makes scooters safer.

This blog was originally published on WRI’s Insights.

Alejandro Schwedhelm is Urban Mobility Associate at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.

Anna Bray Sharpin is a Transportation Associate for Health and Road Safety at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.

Claudia Adriazola-Steil is Deputy Director of Urban Mobility and Director of Health & Road Safety at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.