Are cities like London really the best examples to encourage innovation ecosystems everywhere? Photo by Untalented Guy/Flickr

Innovation in cities has alleviated poverty, reduced wasteful resource consumption and achieved incredible economic outcomes. It’s part of the secret sauce that has led to the primacy of cities in today’s world, with urban areas accounting for 67% of global GDP growth, housing a majority of the world’s population and increasingly driving international politics.

But while we are good at understanding the value of innovation and fairly good at identifying when a place is innovative, when it comes to understanding what it takes to create innovation, we fall flat.

Over 40 indexes compare cities on the basis of innovation. While individually these indexes are rich and helpful to start a discussion, there are significant gaps that make it difficult for cities to swiftly and confidently manage innovation. From a review of these 40 innovation indexes and in-depth analysis of the 12 most relevant, conducted by UrbanDNA in collaboration with a researcher from Stanford University, our research revealed three major shortcomings of our understanding of urban innovation today.

There Is No Clear Definition of Innovation

What do we really mean when we say “innovation?” The term is so widely used that its meaning has meandered. Even among leading innovation experts, there is little agreement. And, when we look at innovation through an urban lens, things blur even further.

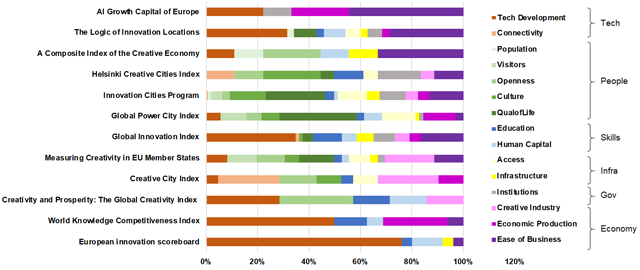

We took a birds-eye view by looking at how 12 of the most relevant innovation indexes define the term. We analysed nearly 500 indicators from these indexes and recategorized them into 15 topics and six themes.

Figure 1: Key Terms Underpinning Prominent Urban Innovation Indexes

The composition of each index is different, from an index that uses 75% of indicators related to technology (the European Innovation Scoreboard), to those that have a similar bias towards business and the economy (London: The AI Growth Capital of Europe, The Logic of Innovation Locations).

While each of these themes and topics is relevant and important, the lack of consistency across indexes prevents cities from seeking a clear a path to innovation performance.

We Measure Inputs, But Cities Seek Impact

Urban innovation does not just occur. It requires careful management, strategic implementation and patience.

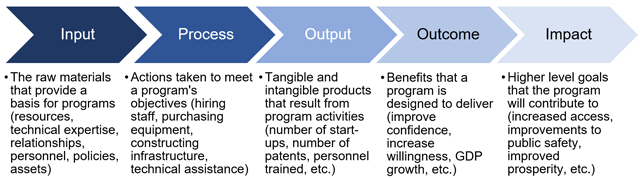

There is a logic and discrete components that make up this process, a framework usually adopted by organizations to show how inputs lead to impact. This pathway is useful for program evaluation and identifying strategies to improve and sustain performance.

Figure 2: Example of a Logical Process to Measure and Deliver Urban Innovation

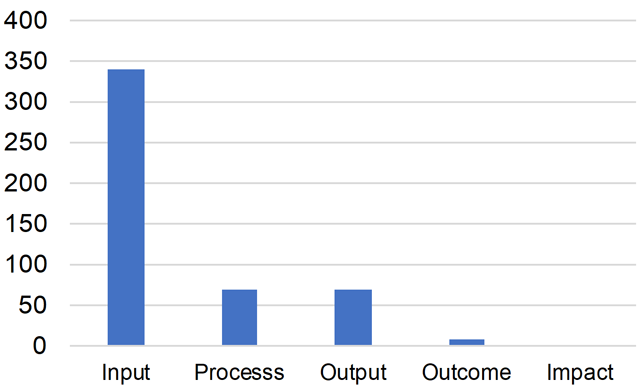

We applied this framework to nearly 500 urban innovation indicators by mapping them against the different categories: input, process, output, outcome and impact. What we found was shocking: 90% of all indicators measure inputs.

Figure 3: Mapping Innovation Indicators Against the Categories of a Logical Framework

Input indicators are perhaps easier to measure, but without the logical connections to process, output, outcomes and finally impact, cities won’t deliver innovation effectively.

Smaller and Developing Cities Are Overlooked

Big cities are the main focus of innovation indexes. Innovation hubs like New York, London, Singapore and Paris boast millions of inhabitants, are located in developed regions and continually rank highly in these indexes. As a result, the baseline for urban innovation is based on the performance of these star cities. But while they are notable for their size, they are actually home to a modest percentage of the world’s urban dwellers. Presently, most people live in smaller cities (less than 500,000 inhabitants). These places arguably have a greater need for innovation.

Smaller cities are often challenged when it comes to leveraging public funds or attracting new talent. Yet, their small size can also offer more agility in decision-making, potentially allowing them to realize innovations faster.

Innovation indexes are also missing out on innovation in developing cities. Regionally, more than 90% of new urban population growth between now and 2050 is expected in Africa and Asia. By 2100, Lagos could host nearly 100 million inhabitants. By 2100, all 20 of the most populous cities are expected to be in Africa and Asia.

Top 20 Cities by Population 2010 vs. 2100

This radical shift poses a serious question: should we be using today’s big cities as exemplars for the cities of tomorrow?

As long as innovation indexes are mainly reflections of today’s biggest and most well-known cities, they may be holding us back from identifying best practices pioneered in smaller, fast-growing cities, where in fact the demand for innovation is most acute.

Now, more than ever, cities must find ways to drive innovation. How cities develop will define our future, and they are beset by major challenges. Leading innovation examples often tell good stories, but cities of all kinds should also be able to share best practices, learn and collaborate with each other to address common challenges.

Innovation indexes are starting points to inform the conversation. However, inconsistent definitions, lack of clear logical process to achieve impact and absence of contextual differences are holding cities back. A common global framework to measure innovation that supports collaboration and standardization would liberate innovation to drive progress in cities.

Kate Gasparro is a National Science Foundation Research Fellow at Stanford University’s Global Project Center.

Francesco Papa is committed to advance cities and joined UrbanDNA to support this journey.

Graham Colclough is founding partner of UrbanDNA.