Worsening traffic in Beijing, China, leads to discussions of congestion charging policies. But what do the people think? Photo by Shiyang Huang/Flickr

Beijing is one of most congested cities in the world, with over 6 million cars on its roads. In 2017, drivers spent on average just under three hours in traffic each weekday. Data from the navigation app AutoNavi shows Beijing commuters lost an average of 1,075 yuan ($159) per month due to congestion in 2017, accounting for 13 percent of the average monthly wage.

As part of an effort to reverse the tide of worsening traffic, Beijing has turned to economic incentives. In December 2010, the city announced 28 measures to improve conditions, including conducting research on congestion charging plans for busy roads. However, in January 2017, legislation on congestion charging was postponed indefinitely due to low consensus.

The sample size is small, but around the world congestion charging tends to be an unpopular policy at the start. There is a natural aversion to any additional fees or taxes, especially for the use of road space, which is often considered a public asset. The benefits of charging for road space, including incentivizing transport modes that take up less space, reducing congestion and pollution, and improving conditions for pedestrians and cyclists, take time to accrue. But in London and Stockholm, where congestion charging has been in place for years, public support rose quickly after implementation.

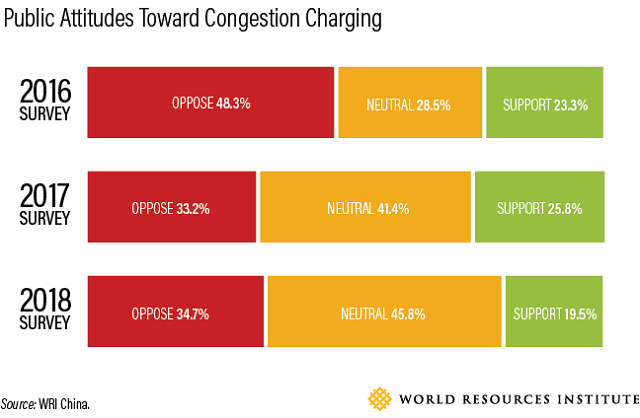

In 2016, to gauge interest in Beijing, WRI China partnered with Beijing Jiaotong University to conduct a three-year public opinion survey. Survey results show that public support for congestion charging has actually decreased slightly, but also that opposition is strongly rooted in particular demographic groups, which may make it easier to make adjustments to ensure smoother implementation. The results also show that many people support the intended goals of the policy.

Who Is Likely to Support and Oppose the Policy?

In three years, the WRI team collected over 26,000 valid questionnaires in Beijing, reaching and educating thousands more. Results show that the share of respondents both for and against the policy decreased and the share of those with neutral opinions increased.

Though it’s not exactly good news for proponents of the policy, the proportion of the public opposed in Beijing is actually lower than that in other cities before congestion charging policies were put in place, including London (55 percent oppose) and Milan (48 percent oppose).

Results show that the more respondents know about the policy, the more supportive they tend to be. Over 40 percent of respondents that knew the policy well supported implementation, while fewer than 20 percent who knew little about the policy were supportive.

Those who highly valued time were more likely to support congestion charging. Forty percent of respondents who were willing to pay as much as 25 yuan (about $3.70) to reduce 15 minutes of their commuting time supported the policy. On average, respondents in Beijing were willing to spend 14 yuan to save up to 15 minutes lost in congestion (average monthly income in 2017 in the city was 8,467 yuan).

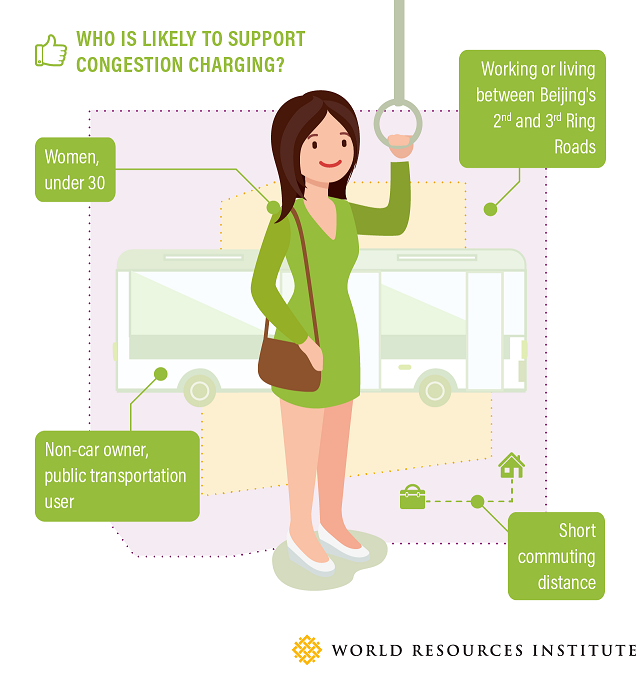

Supporters – mostly younger people, women and those with shorter commutes – widely believe that congestion charging can reduce car use, effectively mitigate congestion and improve air quality.

Opponents – mostly middle-aged men with longer commutes – largely argue that congestion charging will increase burdens on private car owners. They believe that tackling congestion should start with urban planning and transport management, instead of resorting to pricing measures.

Almost half of the respondents expect the congestion fees to go toward improving public transport infrastructure or subsidizing public transport. Another 20 percent of respondents hope the congestion fees will be used to improve bicycling and walking infrastructure.

If the policy were to be implemented, over half of the respondents said they would drive less and shift to public transport for their commutes. Forty percent of respondents said they would drive less and use more public transport in daily life.

Transparency, Comprehensiveness Are Keys to Success

How the government decides to communicate the policy and channel any funds raised will greatly impact the success or failure of congestion charging in Beijing, should it be implemented. In Stockholm, for example, the government indicates where congestion fees go as part of citizen’s annual tax bills.

It’s also important that congestion charging be part of a comprehensive set of transport changes. When London first introduced congestion charging, it also adopted a series of 33 complementary measures that improved public transport services, provided alternative options and optimized signal timing.

Municipal leaders in Beijing are aware of this history. The 28 proposed measures announced in 2010 also include road infrastructure construction, public transport development, walking and cycling improvements, and traffic information systems. In 2018, Beijing optimized 93 bus routes to provide more convenient travel for residents in more than 150 communities, made real-time bus schedule information service available, launched three subway lines, improved 928 km of walking and cycling systems, and implemented traffic restrictions on non-local passenger vehicles. The city hopes to reduce passenger vehicle travel 10 to 15 percent by 2020, based on 2015 levels, and at least 30 percent by 2035. Time will tell if a congestion charge is added to this mix as well.

Shiyong Qiu is a Research Analyst at WRI China.