People take to the streets during the Via RecreActiva in Guadalajara, Mexico. Photo by Via RecreActiva Guadalajara

Closing more than 60 kilometers of major streets to car traffic sounds like a logistical headache for a city of 4.8 million. But Guadalajara did it anyway ‒ and has done it every Sunday for the last 15 years.

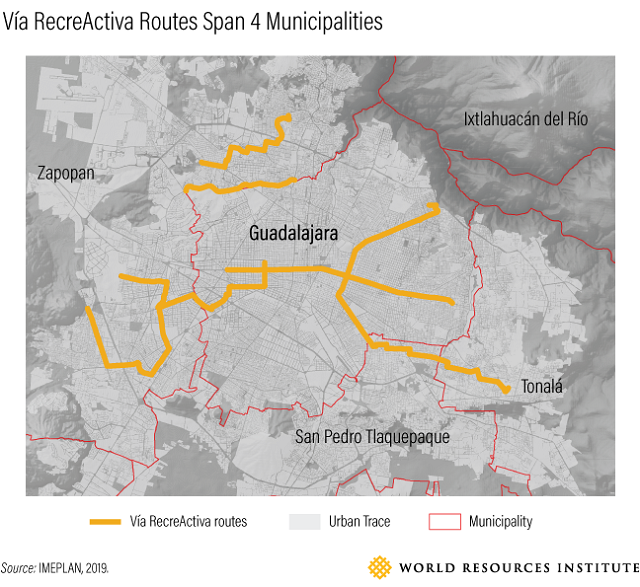

In an event known as the “Via RecreActiva,” Guadalajara, Mexico, closes streets across the city for a ciclovía ‒ a period when bicyclists, pedestrians, shoppers and dancers reclaim public space normally dominated by cars for public recreation. The Via RecreActiva has grown from 35,000 participants each week to more than 220,000.

Establishment of the Via RecreActiva marked an important move towards prioritizing people over cars in Guadalajara, a trend that cities around the world are embracing. Bogotá has hosted a ciclovía event every Sunday for more than 40 years, drawing more than 1.5 million people out of their homes to bike, run and walk in the streets every week. Paris closed more than 400 miles of streets for its fourth annual Journée Sans Voiture. Gurgaon, India has celebrated Raahgiri Day, a car-free event, every Sunday since 2013, a movement which has since spread to several more Indian cities. Los Angeles, Mexico City and Cape Town have all hosted similar events.

These ciclovías are becoming increasingly popular as more cities recognize how repurposing street space for recreation improves the quality of life for city dwellers ‒ it encourages social interaction, provides residents with a sense of connection to the environment and creates a safe space for pedestrians and cyclists.

Nearly one-third of daily travelers in Guadalajara’s metropolitan area are cyclists or pedestrians, but the city has limited safe infrastructure for these travelers, especially in poorer areas to the east. The Via RecreActiva addressed this by designing a route that cuts across four out of the nine municipalities of Guadalajara and hosting events that are open and free to everyone.

A new case study in the World Resources Report, “Towards a More Equal City,” tells the story of the Via RecreActiva. It explains the benefits that can come to a city that invests in car-free space and how these investments can spark broader change towards a safer and more equitable city.

Here are 3 of the benefits that Guadalajara has experienced since establishing the Via RecreActiva:

1. Open Space for Recreation

The Via RecreActiva was originally modeled after the successful ciclovía in Bogotá, Colombia. That project was championed by the former Mayor, Enrique Peñalosa, who saw public-space interventions as economic and community development tactics.

The Via RecreActiva criss-crosses the city, and almost half of attendees arrive on bicycle. As one community member noted, the Via RecreActiva allows for the, “recognition of ‘others’ as occupants of public space with a right to use the street.” Through the Via RecreActiva, these ‘others’, or non-car users, have access to city space that is typically viewed as exclusive for car use. Citizens are encouraged to express themselves through self-run public presentations, concerts, plays and dances, and a sense of community is forged every Sunday as people from across the city come together to enjoy the more than 52 free events held annually.

2. A New Collective Image of Public Space

Ahead of the launch of the Via RecreActiva, groups consisting of journalists, business leaders and urban planners traveled to Bogotá more than ten times to learn from its own ciclovía. When they returned, they started sharing new ideas for sustainable transport and public space use with residents of Guadalajara.

As the Via RecreActiva rose in popularity, so rose the prominence of urban transport and space issues in public discourse, inspiring a new image of what public space and inclusive governance could look like. As one resident said, “the issue of [closing the streets embodied] a more complex idea of public space.” The ciclovía invites people from varying geographic and socioeconomic backgrounds into an inclusive space for recreation and self-expression, and, as another resident noted, “this exercise has built a collective imaginary, a presence, an existence… [of] at least some equity” in public space use.

3. Civil Society as a Champion of Public Space

The parallel rise of civil society activism and political momentum around public space issues perpetuated the ideals of safe and equitable urban space exemplified by the Via RecreActiva. As it was implemented, public and private interests began to coalesce around a shared agenda for urban mobility.

Guadalajara 2020, an initiative led by business owners and activists who were vocal supporters of the Via RecreActiva, helped secure funding and managed government relations for the project. Inspired by the success of the ciclovía, civil society groups including Guadalajara 2020, Colectivo Ecologista and Ciudad Para Todos came together in 2009 to form the umbrella coalition Consejo Ciudadano para la Movilidad Sustentable (Citizen Council for Sustained Mobility). This group established the Master Plan for Non-Motorized Urban Mobility, which set forth rules for incorporating and protecting bike lanes and walkways in public road projects across the city. Jalisco, the municipality of which Guadalajara is the capital, passed the Master Plan in 2010.

Civil society groups like Ciudad Para Todos heard their call to action when the city announced plans to construct an elevated highway, a move that many residents saw as a threat to safe and sustainable transport initiatives like the Via RecreActiva. Public backlash eventually halted the highway. On the back of this success, veterans of these protests formed a new political party called Movimiento Ciudadano in 2015. Its progressive platform focused on bolstering the economic and social wellbeing of all citizens and sustainable urban development for the city. In 2015, the party won the governor’s race and 6 of the 8 municipal elections in Guadalajara’s wider metropolitan area.

Sustaining Transformation

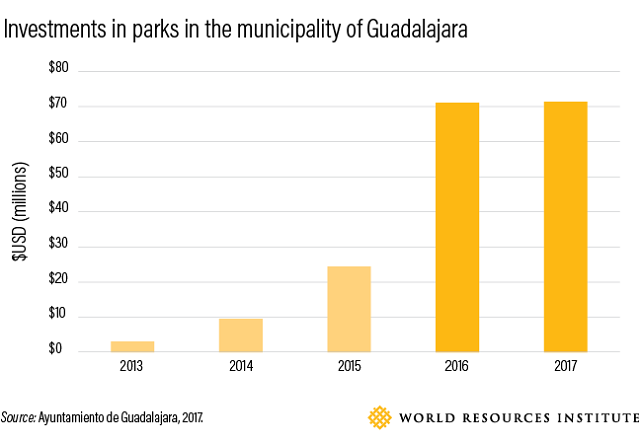

The Via RecreActiva was part of a turn towards dramatic reinvestment in public space in Guadalajara. Between 2015 to 2016 alone, the government of Guadalajara tripled its investment in public parks. Practices such as community consultations around bike paths and participatory budgeting for public works projects have made governance of public space in the city more inclusive.

The Via RecreActiva exemplifies how one public space intervention can alter the social and political fabric of the city. To sustain the kind of positive change seen in Guadalajara, cities should focus resources on projects that benefit the most marginalized communities, avoid displacing vulnerable people in urban development projects and invest in participatory governance processes.

This blog was originally published on WRI’s Insights.

Maria Hart is a Research and Engagement Specialist at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.

Jillian Du is a Research Assistant at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.