Departments that work together on projects and use natural infrastructure, like the Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park in Singapore, can achieve a variety of benefits. Photo by Neil Howard/Flickr

Capital City, a (hypothetical) seaside metropolis, has a growing population. However, much of its infrastructure was built 100 years ago and is straining from deferred maintenance, unable to meet the city’s future needs.

To make matters worse, Capital City has seen damage from increased flooding and shoreline erosion. Its residents, especially those already burdened by environmental pollution, are suffering from increasing heat as well as poor air quality from industry and heavy traffic.

The mayor summons the heads of the city’s major departments to a joint meeting to hear how they plan to address the city’s needs.

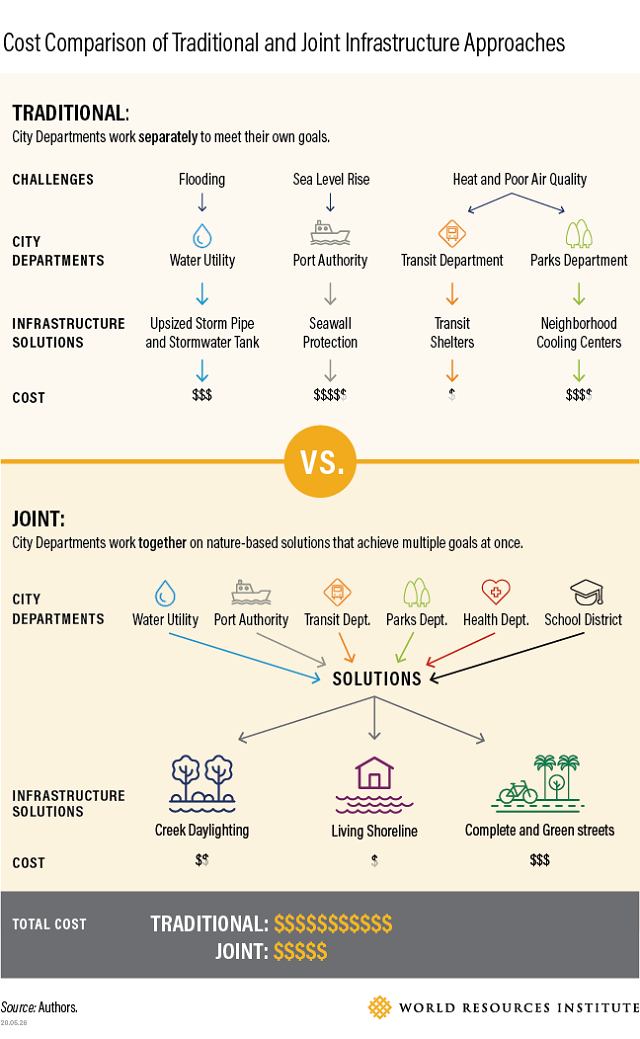

They all present a solution in line with their own department’s mission, each of which would be effective in responding to a specific issue: the head of the Water Utility proposes upsizing pipes and building a large underground tank to hold more stormwater; the head of the Port Authority describes a plan for elevating shoreline streets and building a seawall; the Transit Agency is planning brand new transit shelters for all stations; and the Parks Department proposes new recreation centers that can serve as cooling centers.

The mayor adds up the budget for each proposal and sees that she can’t pay for all of them ‒ so what can she do?

Most cities face a similar conundrum. Retrofitting communities to weather the effects of climate change has an enormous price tag.

With increasing storm intensity, hotter temperatures, rising seas and a level of uncertainty about future conditions, communities are struggling to plan and finance climate-appropriate infrastructure improvements, especially since COVID-19 is already stressing city budgets. But, if departments worked together on integrated projects that utilize natural infrastructure solutions, they could achieve the goals of each department, help the community and realize efficiencies in costs.

Bringing Nature into the City

Research shows that nature-based solutions (also sometimes called “natural” or “green” infrastructure) such as trees, wetlands, parks, open spaces and green roofs can address many of these problems at once. Nature-based solutions serve as multi-benefit infrastructure that meet core community needs while also providing co-benefits. Trees and other plants generate oxygen, aid with carbon sequestration and can mitigate other air pollution, while shading streets and parks, providing wildlife habitat, absorbing rainfall, slowing runoff, boosting mental health and more.

Nature-based solutions, such as greenways and marine habitat restoration on Vancouver’s waterfront, can make communities more resilient while addressing the needs of multiple city departments. Photo by Lisa Beyer/WRI

For example, rather than build costly new “gray” infrastructure, such as upsized pipes and an underground storage tank, water utilities could invest in neighborhood rain gardens, park creek daylighting (restoring streams previously buried in pipes) and tree-lined green streets to collect and hold back stormwater. These green infrastructure measures also address needs from other city departments, such as the health department’s goal of reduced respiratory and heat illnesses, or the transit and school departments’ desire to create safe routes for walking to school, as green streets often have features that help slow traffic.

Similarly, port authorities could pursue living shorelines of marshes and wetlands to stabilize the shore, reduce erosion and protect from storms, all while providing healthy wildlife habitat, public access and recreation.

Building natural infrastructure can also cost less than traditional infrastructure.

Studies estimate that in Los Angeles, a storm drainage system retrofit project would cost approximately $44 billion for traditional gray infrastructure, but would only cost between $2.8 and $7.4 billion with natural infrastructure. Studies in Philadelphia and Washington D.C. found similar cost savings through natural infrastructure.

Adding this up, a joint natural infrastructure approach can help Capital City, or any city, create a resilient community.

Nature at Work in Singapore’s Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park

Since they address so many city needs, nature-based solutions often require a greater degree of inter-departmental collaboration and joint planning from many city agencies. While there are few examples of this type of collaboration, it has been tested.

Singapore’s Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park is a model of how agency collaboration can create an integrated multi-benefit project at a lower cost than the traditional gray infrastructure approach.

Decades ago, Singapore channelized the Kallang River into a concrete canal bordered by fences to control stormwater and flooding. This channel served as a symbolic and literal dividing line between the adjacent residential neighborhoods.

When the canal needed repairs, the Public Utilities Board (Singapore’s national water agency) faced a choice. They could rebuild the existing concrete channel or consider “naturalizing” the river ‒ restoring the riverbed to its natural floodplain.

Naturalizing the river required working with the National Parks Board (Singapore’s parks agency), which managed the land surrounding the canal. The two agencies, with the help of the private design firm Ramboll Studio Dreiseitl, created a new partnership to design and build a daring new “blue green infrastructure” project that amplified community benefits while addressing the needs for flood protection and improved water quality.

Before and after photos of Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park. Photos by Victor Yeo/Flickr and Jnzls Photos/Flickr

Singapore’s National University conducted a cost-benefit analysis and found that simply rebuilding the concrete canal would cost roughly $94 million (133 million SGD), while it cost just under $50 million (70 million SGD) to naturalize the river, as well as expand and interconnect the park space. At almost half the cost of replacing the concrete channel, the joint natural infrastructure approach provides an estimated $74 million (105 million SGD) in benefits annually, more than paying for the investment.

The blue-green infrastructure addressed the city’s needs for a reliable water supply, better water quality and flood management, while creating spaces for people and nature in the city. And because the agencies worked together, they achieved this result at a fraction of the cost.

Scaling Multi-Purpose, Resilient Infrastructure

Projects like Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park set an excellent example of how cities can use nature-based solutions to build better, stronger infrastructure. By working together, from identifying the community’s needs to implementation, city departments can pursue projects that manage stormwater, provide recreation and education opportunities, cool neighborhoods, increase biodiversity, address mobility and expand housing at the same time. We need more projects like Bishan Park, but this sort of inter-departmental collaboration is easier said than done.

Cities need a successful mechanism to jointly plan and fund projects that cross-department jurisdictions and address multiple community needs. That’s why WRI, in partnership with Encourage Capital, is working to develop a framework called the Joint Benefits Authority, which will allow departments within a city to jointly plan, implement and finance these types of transformative projects by quantifying the range of benefits that cross-agency mandates.

We are working with the City of San Francisco, a member of the Cities4Forests initiative, to pilot the new idea, where the team is identifying locations that have multiple challenges, such as flooding, impacts from sea level rise, transportation and open space gaps. If successful, the Joint Benefits Authority can provide communities across the globe with a template to replicate these types of collaborative projects.

The coronavirus pandemic shows that many of our city systems are fragile. It also highlights the stark division between those with and those without adequate public resources and amplifies the vulnerabilities of our underserved communities.

As the world turns to focus on economic recovery efforts, which will likely include stimulus funding to replace aging infrastructure, we face a choice: do we simply patch up the inadequate systems that already exist, or do we build back better with new approaches?

Cities will need to prioritize resilience in order to thrive. Nature-based solutions can help deliver resilient, affordable and equitable infrastructure, but only if departments can work together for the good of their communities.

Read more about the Joint Benefits Authority.

This blog was originally published on WRI’s Insights.

Lisa Beyer is a Manager for Urban Water Infrastructure at World Resources Institute.

James Anderson is an Associate II for the Natural Infrastructure Initiative at World Resources Institute.