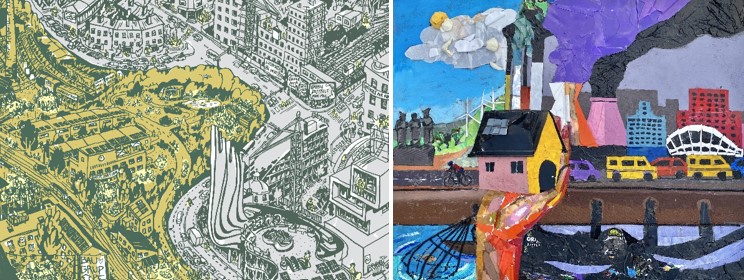

Climate change and social inequality are two of the most pressing challenges of our time. But, in the race to net zero, a narrow focus on decarbonization risks exacerbating inequality and results in a rising tide of “greenlash” (backlash against green initiatives)—wasting time, wasting money and stalling progress. An unjust transition where residents lose homes and workers lose jobs will result in increased political polarization, instability and insecurity that will negatively impact government, business, people and planet.

This is why green policies must be grounded in human rights.

Over the past two years, the Institute for Human Rights and Business (IHRB) has undertaken research in eight cities to uncover the human rights risks and opportunities associated with their green transitions, and provide tools, recommendations and guiding principles for businesses and policymakers to grasp the enormous opportunity for social and economic innovation provided by climate action.

Buildings and construction contribute 37% of global energy-related carbon emissions, and cities are often where people experience the most severe impacts of climate change, rising cost of living and socioeconomic inequalities. Over the past 10 years, governments and businesses all over the world have launched decarbonization initiatives, from renewable energy schemes to building retrofits and new green spaces.

But climate action, like climate change, is not affecting everyone equally. A new subsidy for solar panels is more likely to benefit homeowners than those living in informal settlements or experiencing homelessness, who are already more vulnerable to climate change-induced disasters, extreme temperatures and sea level rise. From Germany to Nigeria, France to the U.S., communities negatively impacted by climate action are pushing back against new heat pump requirements, incentives to phase out gas stoves or new eco-cities that may negatively affect them.

To increase public support for, and ultimately accelerate, climate action, decarbonization initiatives must be grounded in international human rights. These emphasize the roles of states and businesses in protecting the rights of vulnerable groups, shifting the perception of climate initiatives from elite-driven to inclusive, grassroots-supported efforts. This rights-based approach is central to the concept of “just transitions,” first championed by trade unions and increasingly recognized by policymakers, investors and stakeholders.

A just transition aims to achieve two interconnected goals:

- Environmental Goal: Shift to economic models that allow development within planetary boundaries.

- Social Goal: Ensure the benefits of this shift are equitably distributed, and the costs do not disproportionately impact marginalized communities.

In the course of our research, we uncovered examples of where green initiatives are exacerbating social problems. In Prague and Lisbon, publicly-funded housing retrofit programs are resulting in unaffordable rent increases, a phenomenon known as “renovictions.”

In Lagos, Nigeria, the Eko Atlantic project set out to protect the city from coastal erosion by building a new, eco-friendly city. However, in doing so, it displaced a community of 80,000 low-income workers and turned a publicly accessible beach into a privatized, green gated community.

But there are local authorities and businesses taking a different approach.

Indonesia’s Green Affordable Housing Program, for example, is aiming to deliver 1 million affordable green homes by 2030 through a combination of new builds and deep retrofits.

To reduce the risk of renovictions while still incentivizing retrofits, some Belgian regions have introduced a clever mix of policies: rents must remain frozen on poor-performing homes, but – even for the most energy efficient ones – they can only be increased at the rate of inflation. In Milan, the city prioritizes rent-controlled social housing when rolling out building retrofits, and, in Athens, the development of a new eco-city is proposed on the grounds of an old airport, avoiding any displacement.

With over 11 million empty homes across Europe alone, cities like Brussels and Vancouver are introducing empty homes taxes and grants to convert them into much-needed affordable homes. Governments are also looking to increase the public housing stock, with Paris introducing a “right of first refusal scheme” whereby large buildings can only be sold on the open market after being offered to the city at a market rate.

While our research clearly highlights the negative impact of large-scale, global corporate landlords on housing affordability, some private actors are trying to buck the trend and deliver affordable, sustainable homes.

Home.Earth in Copenhagen hands back part of the income to tenants, who are also supported by a no-eviction policy, while Inclusio delivers green housing for low-income communities and disabled residents.

The transition is creating new green construction jobs, but there was mixed evidence as to whether these are going to the people who are losing high-carbon jobs and whether they provide improved working conditions in a sector where jobs are often precarious and dangerous.

There is no way to reduce inequality without tackling climate change, but this research highlights that it will also be impossible to reach our climate goals without reducing inequality. Contrary to populist narratives, equity and decarbonisation are not mutually exclusive, but mutually reinforcing processes. In fact, putting people first is the key to unlocking and accelerating climate action in the built environment. Ultimately, it’s clear that respecting people’s fundamental rights is the only way we can create the fair and sustainable societies we need for people and planet to survive and flourish.

Giulio Ferrini is Head of the Built Environment Program at the Institute for Human Rights and Business.