Transportation connects us to one another. It’s how we get to school and work, how we visit our families, and how we access our food and health care. It’s also how we ship goods and deliver services. As economies and populations grow, so does the need for efficient, accessible and sustainable transportation.

The current global transport system accounts for 15% of global greenhouse gas emissions, which continue to grow. In 2019, 71% of transportation-related greenhouse gas emissions came from roadways alone (with the rest primarily from maritime and aviation, and a small portion from rail and other sources). Transport has been a laggard for years, with the sector falling behind others, like power and heating, in its decarbonization rate. To limit global warming to 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F) and prevent some of the worst impacts of climate change, we need to reverse course and drive transportation emissions down as low and as quickly as possible.

Our current global transport system accounts for 15% of global greenhouse gas emissions per year

In 2019, 72% of transport-related greenhouse gas emissions came from road transport alone, with the rest made up of shipping, aviation, and other sources

Shifting to electric vehicles will play an important role but transforming transportation will take real systemic change. What does a systems approach involve? Solutions must bring jobs and services closer to where people live as well as promote public transportation, walking, cycling and other low-carbon and clean-energy transportation alternatives. Finding new solutions to decarbonize shipping and aviation are also crucial.

There are five major shifts identified by Systems Change Lab that, if achieved together, can drastically reduce emissions and spark the necessary change for the planet and people to thrive:

1. Guarantee Reliable Access to Safe and Modern Mobility

Future transportation systems — in addition to being low-carbon — must be safe, modern and center around improving health. For example, expanding the infrastructure around public transportation systems with dedicated walkways or bike paths will not only combat vehicular congestion and reduce air pollution, but will also encourage more physical activity such as walking, cycling or using scooters.

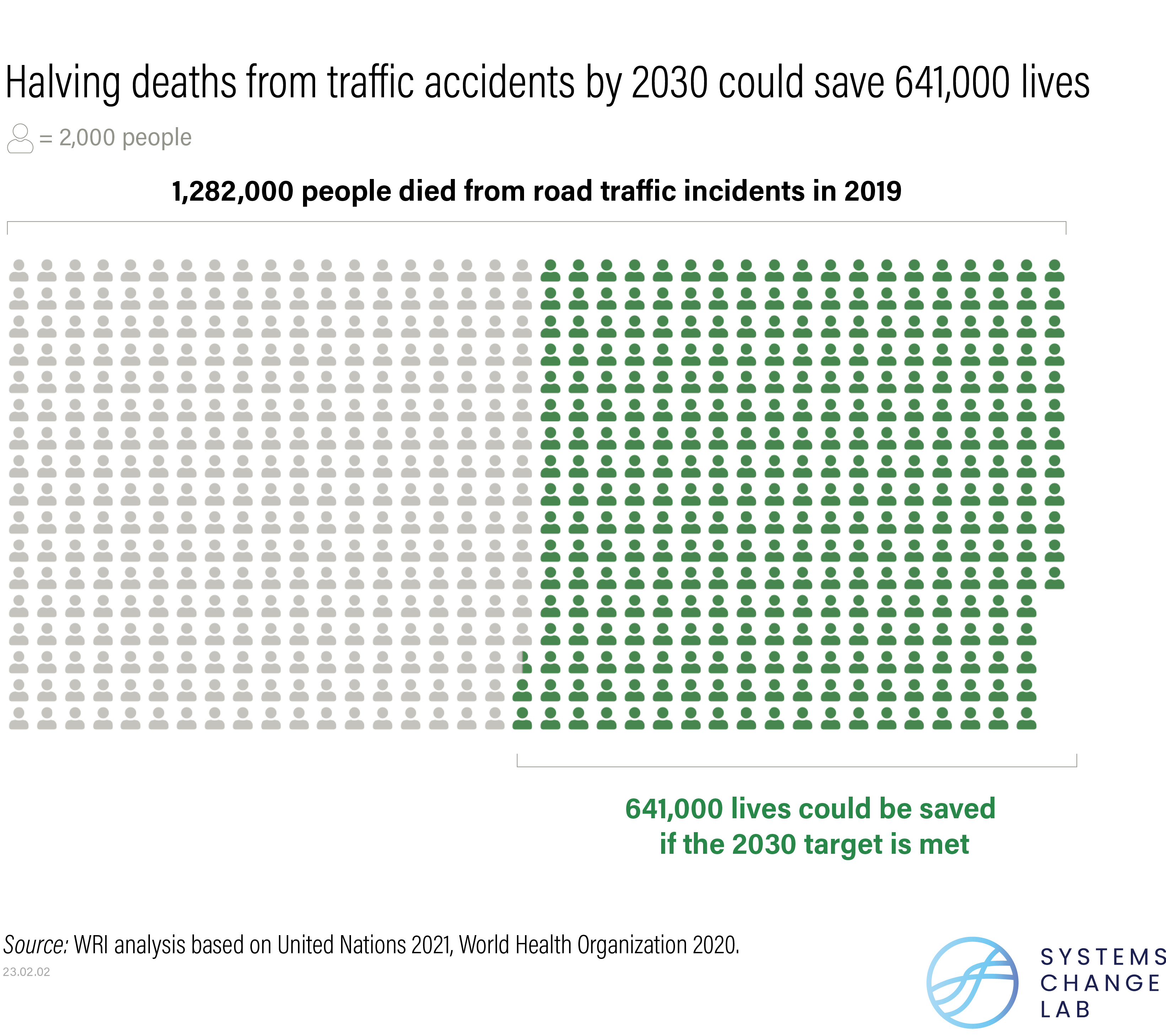

A safer system will also prevent crashes and death associated with vehicle travel. About 17 out of every 100,000 people in the world were killed on roadways in 2019, and nearly half of them were pedestrians or cyclists. In 2021, the United Nations set a target to halve injuries and deaths from road traffic crashes by 2030. Achieving this goal requires concerted efforts to protect pedestrians, cyclists and drivers alike, such as improving street designs, creating protected bicycle lanes and enforcing traffic laws.

Transportation systems must also be affordable and accessible to all. This has not always been the case — for example, women face potential danger from unlit bus stops and potential harassment on public transit. This kind of consideration is often left out of transportation planning. Fortunately, some cities are already working to tackle these challenges — the city of Peshawar, Pakistan recently launched a bus rapid transit system that addresses common issues facing cisgender and transgender women as well as people with disabilities on public transit.

2. Reduce Avoidable Vehicle and Air Travel

The switch from internal combustion to low- and zero-carbon technologies is vital but also unlikely to happen fast enough to decarbonize the entire transportation sector at the necessary speed and scale. Even a complete electrification of cars, buses and trucks would pose challenges due to the increased electricity demand. We need solutions that will also help solve other problems such as traffic congestion, threats to pedestrian safety and inequitable transportation access.

Because of this, in parallel with the electrification process, we must also change the way we move around by limiting the most carbon-intensive forms of transportation, such as cars and airplanes.

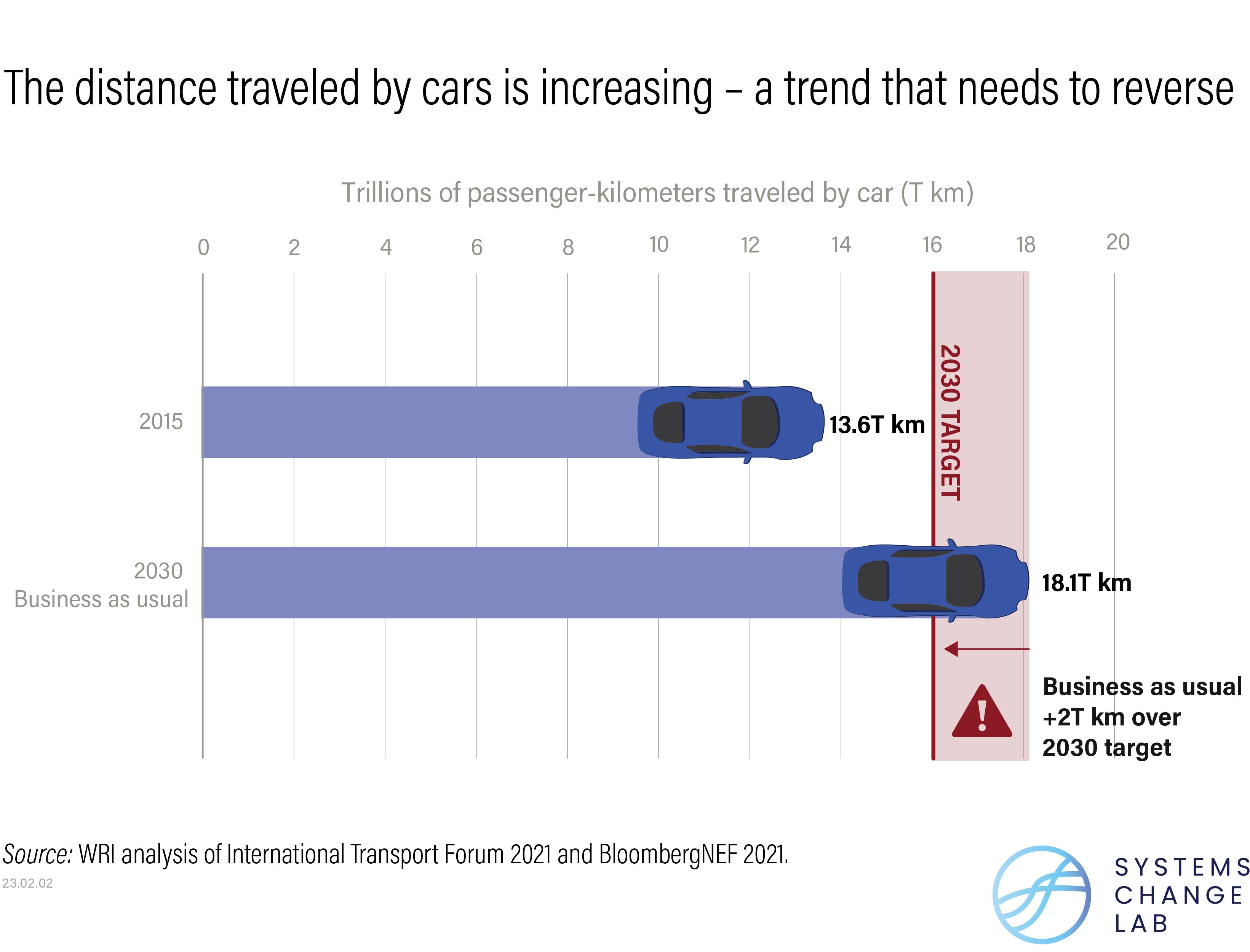

Globally, the distance traveled by passenger cars is rising. This is especially noticeable in high-income, car-dependent places like Europe and North America. The share of kilometers traveled by passenger cars grew to 44% in 2020, and without intervention, this is expected to reach 50% in 2030. To reverse this trend, we must ensure people around the world have access to high-quality, safe alternatives such as high-speed rail or well-designed local bus systems. Bringing the share down to 34% to 44% by 2030 would help get the transportation system on track to keeping global warming below 1.5 degrees C.

To reduce car dependence, cities can also embrace higher-density development, devising new ways to increase access to shops, services and leisure opportunities without needing vehicles. Cities can also disincentivize automobile travel through increased parking costs, fuel taxes or congestion-charging schemes.

However, these policies could hurt those who may not have the means to pay and who rely on cars as their only transportation option. Thus, policies to discourage car travel must be paired with sufficient alternatives, such as increasing safe public transportation options.

Strategies such as fuel taxes and frequent flier levies are also helpful to restrict airplane travel. For short-distance or moderate-distance flights, it is possible that as much as 15% of all regional trips taken by plane could instead be served by high-speed rail. Increasing the quality and affordability of alternatives to plane travel, such as trains and ferries, is essential to boost ridership.

3. Shift to Public, Shared and Non-Motorized Transport

Currently, almost three quarters of transport carbon dioxide emissions come from road travel —largely from cars, vans, buses and trucks. Convincing drivers to shift to more efficient modes will require fundamental cultural change around the car-centric design of many cities. This, alongside holding back car adoption in places where cars are not as prevalent, will be driven by investments that vastly improve other modes of travel.

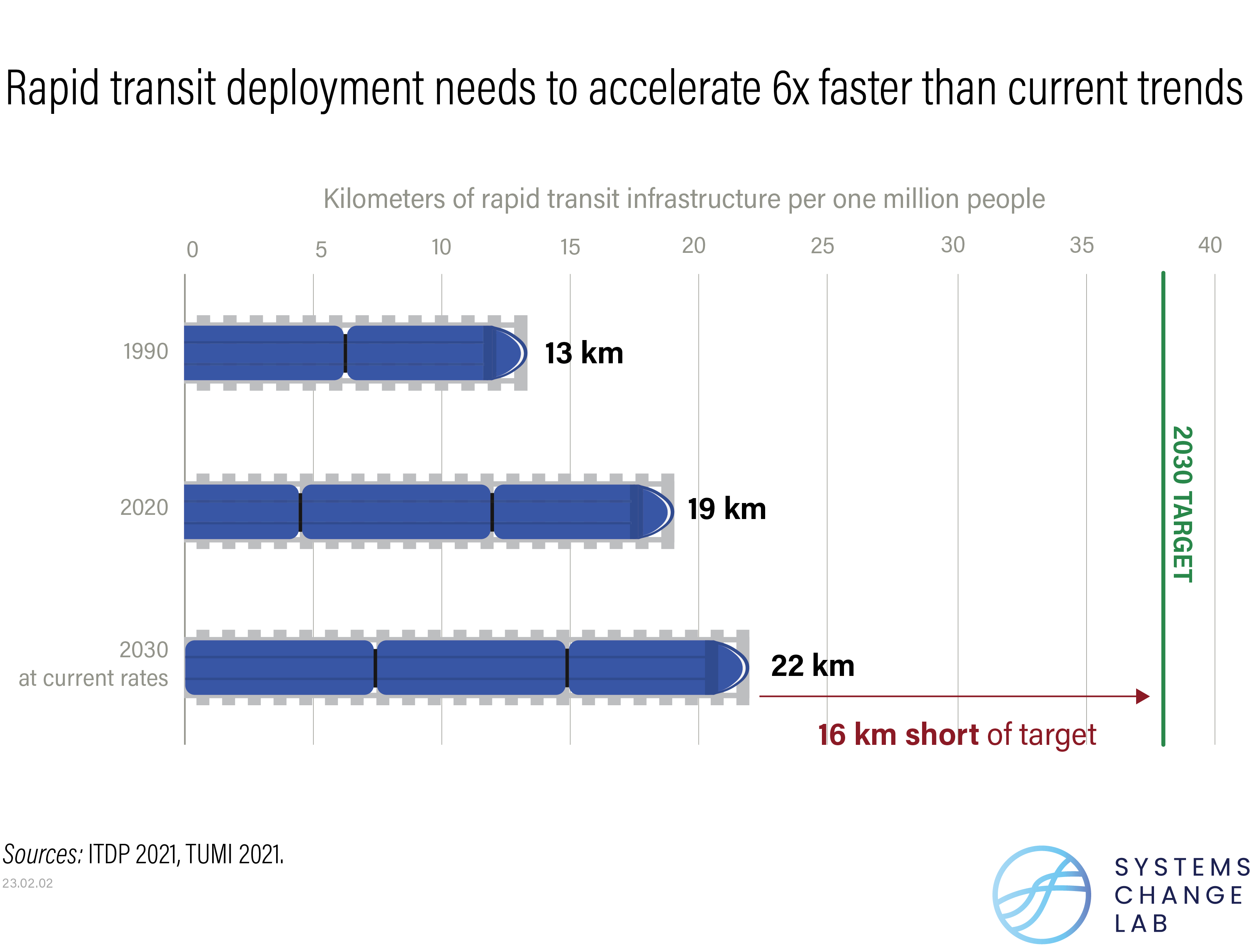

Across the 50 highest-emitting cities, rapid transit tracks and infrastructure increased from about 13 kilometers (roughly 8 miles) per million people in 1990 to about 19 kilometers (or nearly 12 miles) in 2020. At the same time, the length of high-quality bike lanes increased by 6.5 kilometers (4 miles) per person from 2015 to 2020.

Growth in these indicators is a step in the right direction, but recent progress will have to accelerate by 6 times for rapid transit and more than 10 times for bicycles by 2030, to help steer the world toward a 1.5 degree C-compatible scenario.

Alongside crucial emissions reductions, these changes will bring far-reaching benefits for public health and quality of life. A reduction in car usage could open more spaces for walking and cycling, public parks or outdoor dining and socializing. As of 2022, there are 11 countries with targets to shift away from car travel and prioritize public transport — including India and China. As of 2019, 103 countries had plans for walking and bicycling infrastructure.

4. Transition to Zero-Carbon Cars, Trucks and Buses

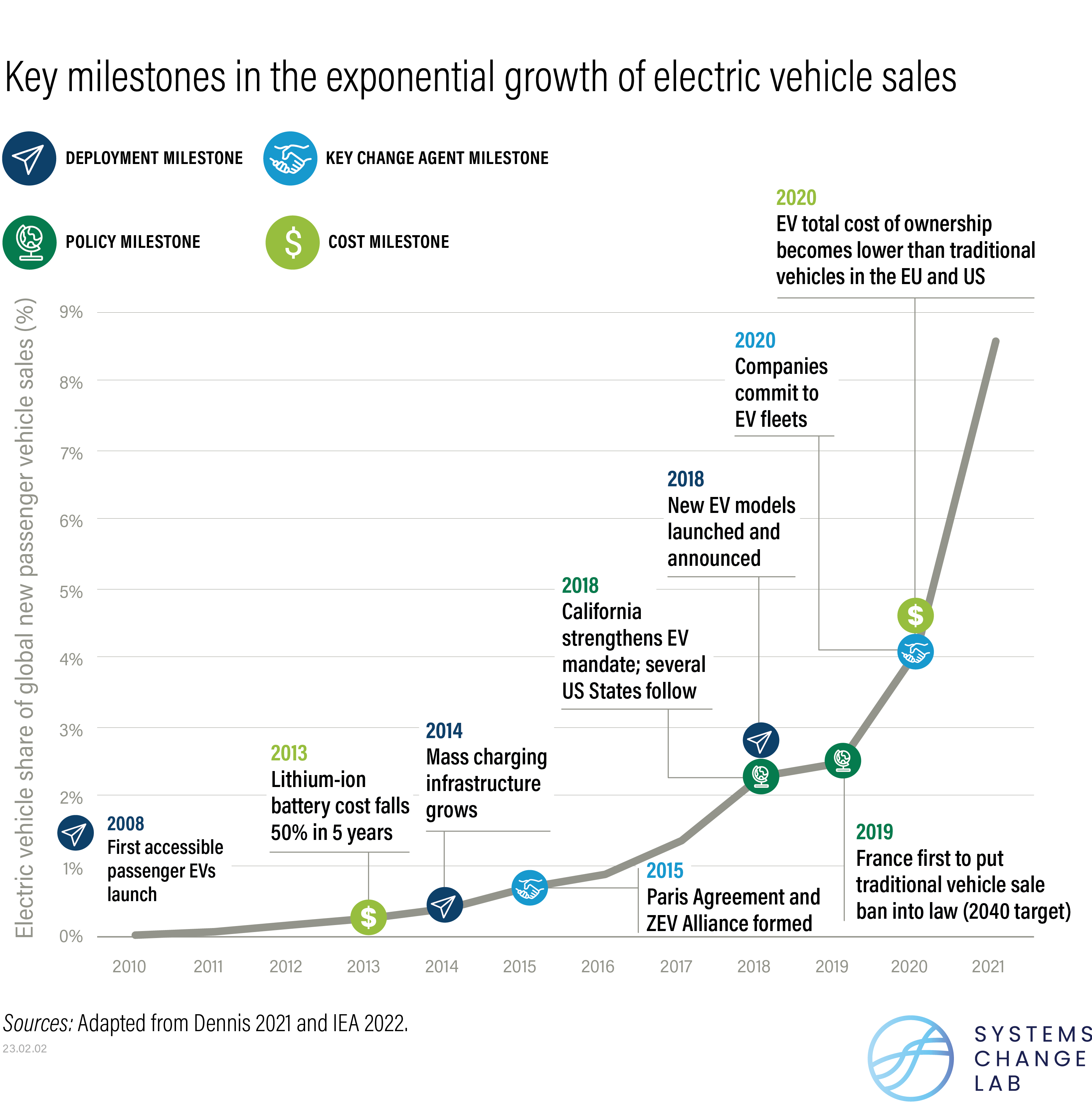

We need to phase out fossil-fuel-powered vehicles as fast as possible. Fortunately, electric vehicles (EVs) provide a similar service without directly emitting carbon dioxide or air pollution. While EV uptake numbers are surging, it’s not fast enough.

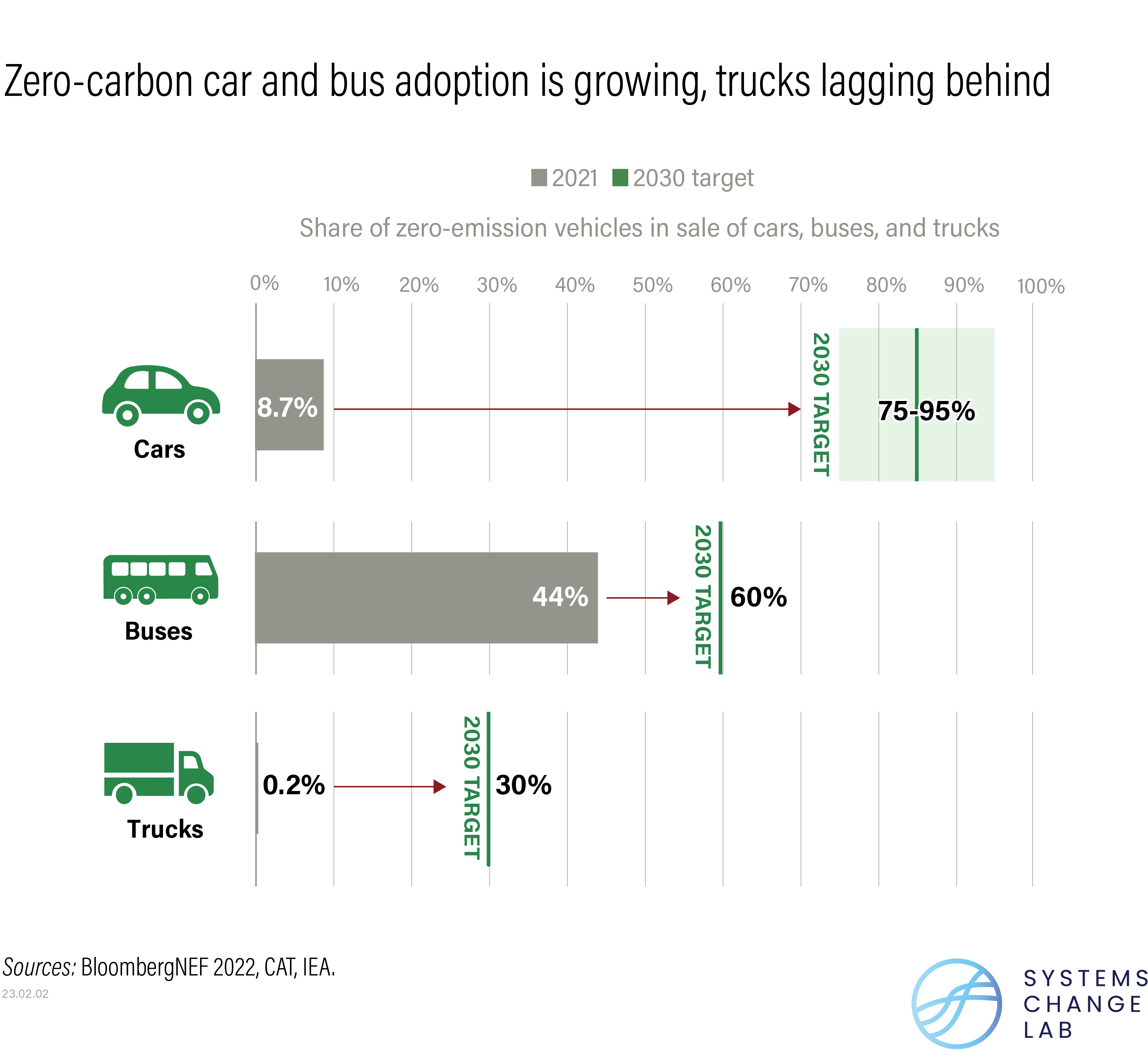

To stay on track to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees C by 2030, all new cars sold globally need to be electric. In 2021, only 8.7% of new cars were electric. EV sales are rising rapidly thanks to improving economics and government support, and dozens of countries plan to end sales of gas and diesel cars by or before 2040. However, recent progress needs to accelerate by 5 times to meet global climate goals.

EVs’ upfront costs are falling, largely due to declining battery prices. It’s been expected to reach price parity with fossil-fuel-powered vehicles across Europe by 2027 (although recent supply chain interruptions have likely pushed this back a few years). In some countries, like Germany and the Netherlands, it is already cheaper to own and operate some types of EVs than their fossil-fuel-powered equivalents. It is reasonable to assume that hitting the milestone of price parity will represent a tipping point that could contribute to accelerated growth in sales.

A rollout of integrated charging networks is needed to speed EV adoption. The number of public EV chargers around the world reached 1.8 million in 2021. Policies to push electrification are emerging in many countries. As of 2021, there were 18 jurisdictions — including Norway, the United Kingdom and Singapore — with targets to phase out the sales of fossil-fuel-powered cars. A complementary policy, a zero-emission vehicle sales mandate, has shown up in 47 jurisdictions — including California, China, and the United Kingdom — as of 2022.

This zero-carbon transition must also occur for buses and trucks. Government ownership of many bus fleets can make them low hanging fruit in this respect because they can make decisions about large fleets with predictable schedules: battery electric and hydrogen buses made up 44% of global bus sales in 2021. To reach our climate goals, this number needs to be 100% by 2030. Progress has been uneven in recent years as most sales have taken place in China, but increasing sales in other regions like Europe and North America are likely to continue to push progress forward. Electric buses have surged in the United States over the past few years — a large purchase by a Midwest transit operator brought the total from just over 2,000 electric school buses in the third quarter of 2021 to just over 13,000 at the end of 2022.

Medium- and heavy-duty trucks are more difficult to decarbonize. Just 0.2% of medium- and heavy-duty truck sales were electric or hydrogen-powered in 2021, and there is an urgent need to bring technologies to commercial maturity. This will require more manufacturers offering hydrogen and electric options, more countries setting targets for phasing out gas-powered vehicles, and more places building charging infrastructure.

5. Transition to Zero-Carbon Shipping and Aviation

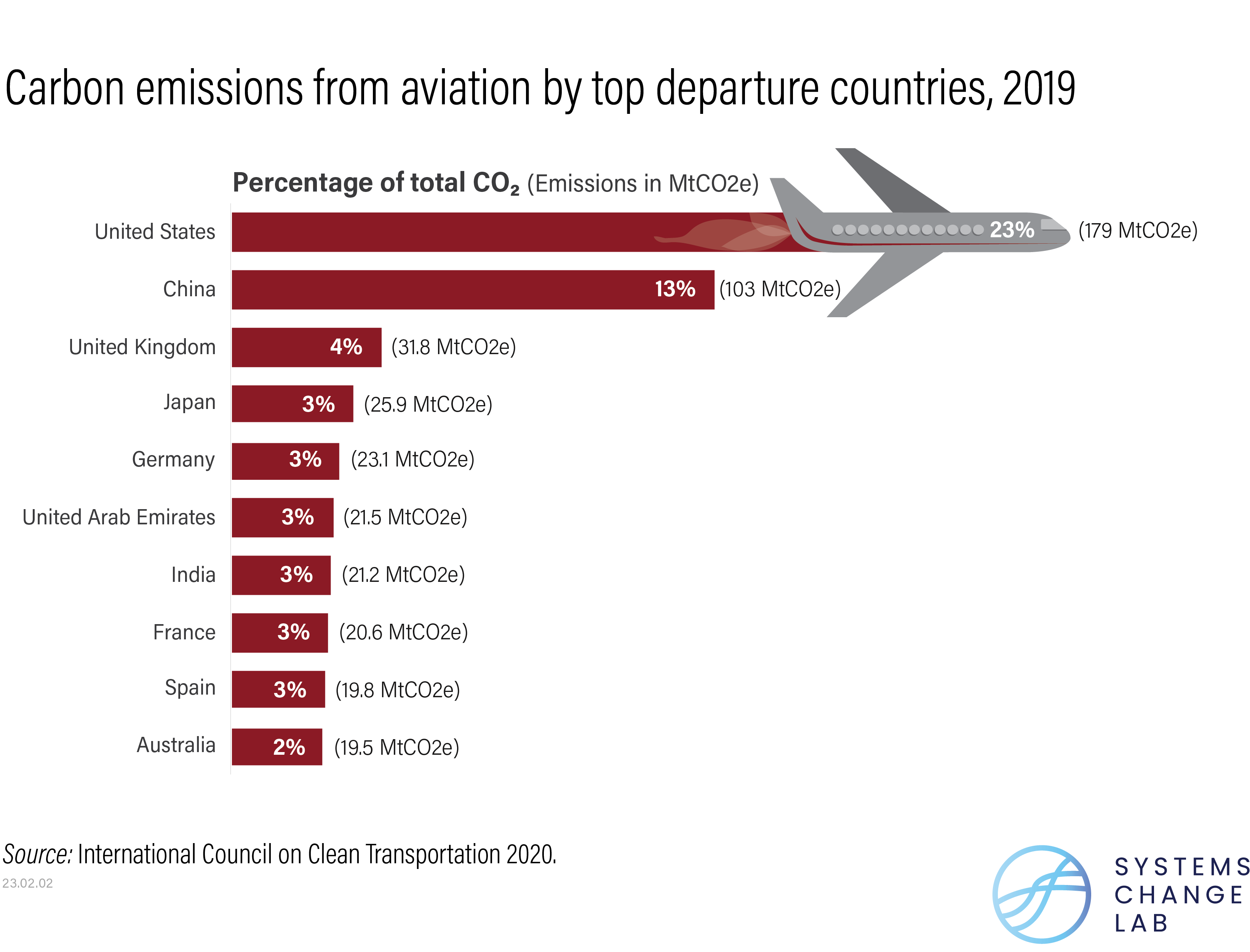

Both shipping and aviation are seen as hard-to-decarbonize sectors, where zero-carbon technologies are still in infancy. Each is responsible for around 3% of global greenhouse emissions.

However, both sectors have pathways to a greener future. Decarbonizing shipping and aviation will require a combination of technological solutions such as zero-emission fuels and batteries alongside operational and efficiency improvements.

For shipping, 5% to 17% of fuel needs to be zero-emission by 2030 to stay on track to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees C. By 2050, 87% to 100% of fuel needs to be zero-emission. Green hydrogen and ammonia, which can be made with renewable electricity, are typically viewed as the most promising fuels to decarbonize shipping. Synthetic fuels made from electricity, hydrogen and captured carbon may also play a part, and batteries could be useful for short-distance trips. Pilot projects will play a key role by helping to prove technical feasibility and demonstrate commercial viability — as of 2022, there were over 200 pilot projects underway.

For aviation, zero-emission options are beginning to emerge, including sustainable aviation fuels made from green hydrogen and captured carbon dioxide or sustainably sourced biomass. Biomass-derived sustainable aviation fuels are the only zero-emission solution commercially available in 2022, but new demonstrations of zero-emission planes are increasing. The share of these fuels needs to rise from less than 0.1% now to 13% to 18% by 2030 and 78% to 100% by 2050, supported by policy incentives.

It is key that zero-emission fuels are not derived from unsustainable biomass sources, such as food crops, which could make it harder to feed people, protect biodiversity and sequester carbon in natural ecosystems. Generally, a massive scaling up of investment and policy is needed in this shift.

Transforming a Global System

Together, these five shifts can transform our global transportation system. They offer a new system where opportunities and services are easily and equitably accessed through clean, safe mobility from walking to electric buses to bike share programs; a system where planes run on clean fuel and road crashes are not the leading cause of death in children; a system where high-speed trains are prevalent and popular.

Of course, this is only possible if we rapidly accelerate progress in these shifts to meet climate and equity targets in this decisive decade.

Systems Change Lab monitors, learns from and mobilizes action toward the transformational shifts needed to protect both people and the planet.

This article originally appeared on WRI’s Insights.

Stephen Naimoli is an Associate for Systems Change Lab.

Brynne Wilcox is a Communications Coordinator for Systems Change Lab.