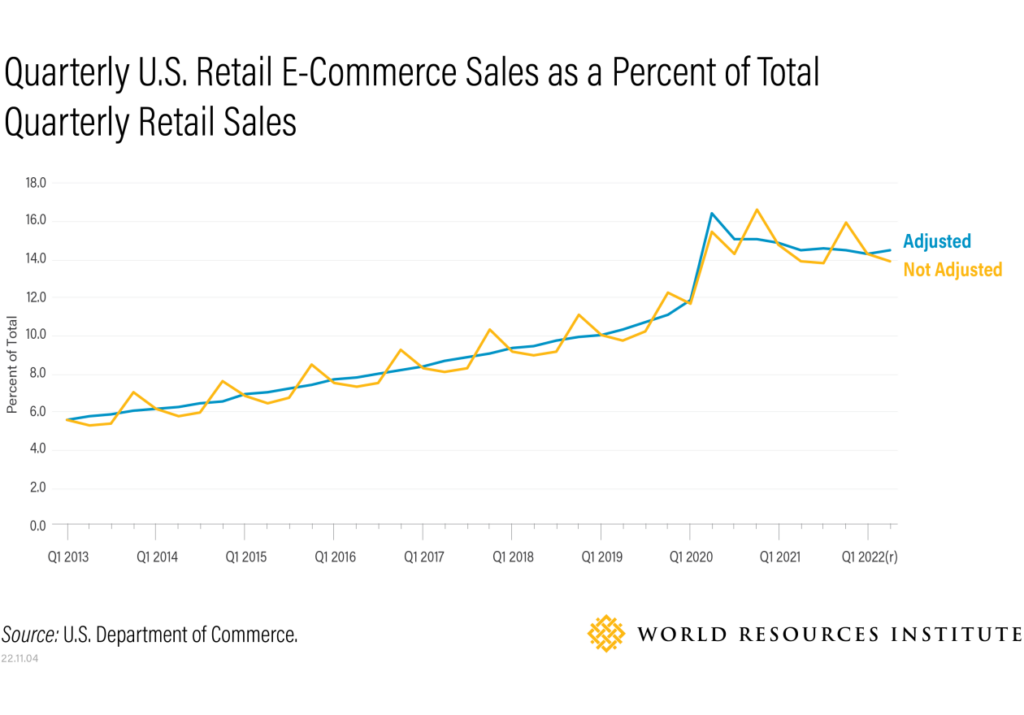

Urban freight and delivery services boomed during the COVID-19 pandemic as consumers switched to online shopping when businesses were forced to close. The surge in online market activity that began in 2020 builds on a decade of steady growth related to the development of new delivery services, changing demographics and globalizing supply chains.

Rising urban freight and delivery activity produces serious environmental and human health consequences, particularly poor air quality, higher greenhouse gas emissions and increased traffic congestion, which can be especially detrimental to low-income communities. In response, city policymakers are exploring innovative freight solutions that can not only decarbonize the sector, but potentially advance social and economic equity and improve quality of life.

A WRI paper details these recent trends and the increased support for zero-emission delivery, performed using zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs), including different electric vehicle types, fuel cell vehicles and bikes. Applying insights from interviews with stakeholders in the United States and the Netherlands, the paper also details the concept of zero-emission delivery zones, a scalable strategy to accelerate the transition to zero-emission delivery.

Here, we offer a primer on how zero-emission delivery zones work:

Zero-Emission Delivery Zones in Practice

Zero-emission delivery zones are areas in which only zero-emission vehicles have unrestricted access, with fossil fuel vehicles either prohibited from entry or required to pay a fee for access. Although zero-emission delivery zones can be thought of as large, cordoned off areas, our research indicates that they can actually take many different forms:

Types of Zero-Emission Delivery Zones (ZEDZ)

|

Country |

Description | Example |

| Voluntary Restricted Access Zone |

A specific area that is designated for ZEVs only, but compliance is

voluntary for urban freight and delivery businesses. |

Santa Monica ZEDZ |

| ZEV Microhub |

A drop-off/pick-up location that serves a small service area and can

be targeted to different types of ZEVs. |

Seattle Neighborhood Delivery Hub |

| ZEV Parking Spots and Loading Zones | Reserved spaces that provide valuable curbside access only to ZEVs. | Los Angeles Zero-Emission Commercial Loading Zones |

| Mandatory Restricted Access Zone |

A defined area in which internal combustion engine vehicles are

prohibited or charged for entry; violators are penalized. |

Rotterdam ZEDZ |

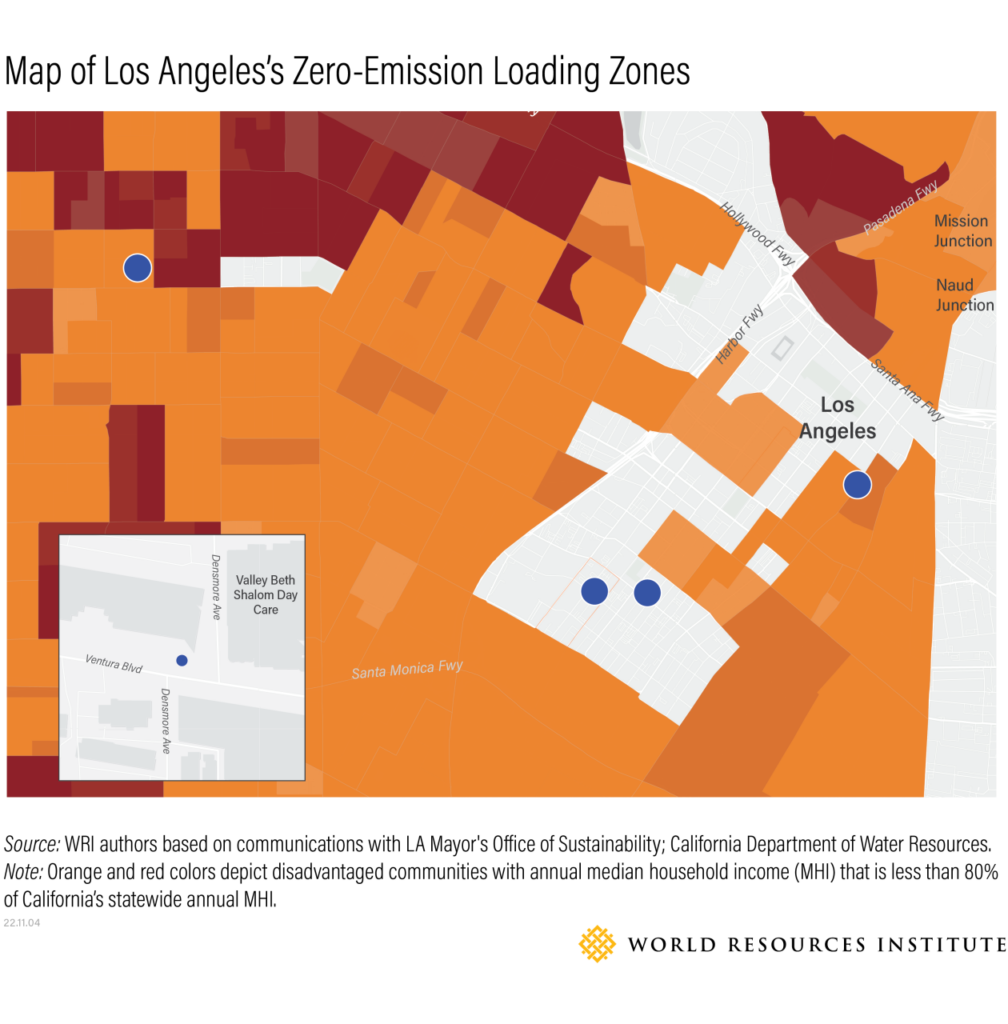

Los Angeles: Zero-Emission Commercial Loading Zones

For example, the city of Los Angeles has long been plagued by local air pollution and persistent traffic congestion, largely due to commuter traffic and urban freight and deliveries. The city is aggressively exploring transportation solutions that can mitigate these problems while reducing the city’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Over the past several years, Los Angeles has pledged to promote mass transit and the transition to ZEVs and zero-emission delivery, signing onto agreements like the C40 Cities Green and Healthy Streets Declaration, which commits the city to reserve an area for only ZEVs by 2030.

Recently, Los Angeles has pursued its own version of a zero-emission delivery zone with a 2021 curbside management ordinance, which allows the city to create five zero-emission commercial loading zones. The city prioritized zero-emission loading zones in areas with high density, disproportionate air pollution burdens, high commercial loading zone demands, and that were under the LA Department of Transportation’s administrative authority to install, enforce and monitor.

Unlike the neighboring city of Santa Monica, which temporarily designated a city area for ZEVs as part of a voluntary zero-emission delivery zone pilot program, Los Angeles focused only on curbside management. Parking and curb space is at a premium in the city, especially for carriers delivering goods to businesses and homes. The zero-emission commercial loading zones are intended to promote ZEV adoption by ensuring reliable parking.

Importantly, the curbside ordinance gives the city the authority to issue fines and citations, a key deterrent to would-be violators.

Los Angeles’ strategy also prioritized placing zero-emission loading zones in communities with high air pollution, reflecting an emphasis on environmental justice. If the policy has the desired effect and increases ZEV adoption, these loading zones could help improve air quality in burdened communities.

The program is still in its early days, and at its current scale, it’s unlikely to greatly impact the local zero-emission delivery vehicle market or produce measurable environmental benefits. However, the approach represents a scalable solution that can evolve alongside changing city policy goals. If expanded, zero-emission loading zones could discourage fossil fuel vehicle use in specific areas, incentivize a shift to zero-emission delivery throughout Los Angeles, and reduce residents’ exposure to air pollutants like particulate matter and nitrous oxides.

Preliminary Guidance for Effective and Equitable Zero-Emission Delivery Zones

With zero-emission delivery zone implementation in the United States and around the world only just beginning, there is little quantitative evidence detailing what policies and designs work best. However, our research points to five recommendations for policymakers:

1. Engage stakeholders early and often.

By engaging with carriers, receivers and communities, city policymakers can better understand the distribution of benefits and burdens from existing urban freight and delivery services, which can facilitate an effective, equitable zero-emission delivery zone design. Stakeholder engagement will also help policymakers identify allies for partnerships and engage detractors to determine shared goals.

2. Take a stepwise approach and build up to a zero-emission delivery zone.

Cities can mitigate early opposition and challenges through a stepwise approach that can quickly produce results while providing flexibility in beginning the zero-emission transition. This approach has its challenges, including determining an appropriate timeline, imposing repeated upgrade costs on stakeholders, and maintaining buy-in throughout the process.

3. Provide supportive policies for successful and inclusive zero-emission delivery zones.

Supportive policies, like purchase subsidies, can support the successful implementation of zero-emission delivery zones by addressing common challenges such as ZEVs’ high capital costs. Initiatives that expand vehicle charging networks and cargo-bike lanes are a few ways to facilitate the ZEV transition. These policies should be designed to advance social and economic equity, ensuring they are used by those who need them most rather than simply where they can be afforded under the status quo.

4. Reform state and federal policies.

Cities implementing zero-emission delivery zones and other ZEV policies may encounter regulatory and cost roadblocks. With the support of involved businesses, cities should pursue expanded regulatory authority, funding support, and policy guidance at the state and federal level, which will enable cohesive policy enforcement and accelerate the ZEV market.

5. Prioritize equity at every step of the process.

As policymakers design their zero-emission deliver zones and supportive policies, they must recognize the inequities within and produced by the freight sector and the affordability and benefits-distribution challenges of the ZEV transition. Communication with businesses, carriers and residents can help policymakers select the best practices to mitigate costs and ensure the benefits of ZEV adoption reach priority areas throughout their cities.

Making Progress on Zero-Emission Delivery Zones

As policymakers consider zero-emission delivery zones and other transportation solutions, they must weigh how to maximize benefits to communities overly burdened by freight and delivery activity while minimizing costs to small carriers and freight-dependent businesses. Without proper design and implementation, zero-emission delivery zones and supportive policies could exacerbate existing inequities, such as diverting polluting freight traffic through neighborhoods outside the zone or failing to supply small businesses in the zone with the necessary financial support to purchase ZEVs.

Our recommendations address some of these concerns, but because the concept of zero-emission delivery zones is in its earliest stages, the policy landscape and best practices will continue to evolve. In addition to our own research, policymakers and other stakeholders should consider other resources for best practices and guidance. We encourage continued efforts to study effective design features and supportive policies.

This article originally appeared on WRI’s Insights.

Hamilton Steimer is a Research Analyst for E-Mobility with WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.

Vishant Kothari is a Manager for the Global Electric Mobility team at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.