The long-awaited COP26 climate summit in Glasgow has come to a close, making important progress in a number of areas — but not enough. The world still remains off track to beat back the climate crisis.

Recognizing the urgency of the challenge, ministers from all over the world agreed that countries should come back next year to submit stronger 2030 emissions reduction targets with the aim of closing the gap to limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F). Ministers also agreed that developed countries should urgently deliver more resources to help climate-vulnerable countries adapt to the dangerous and costly consequences of climate change that they are feeling already — from dwindling crop yields to devastating storms.

Beyond the Glasgow Climate Pact, at COP26 countries also made bold collective commitments to curb methane emissions, to halt and reverse forest loss, align the finance sector with net-zero by 2050, ditch the internal combustion engine, accelerate the phase-out of coal, and end international financing for fossil fuels, to name just a few. Glasgow was a platform for launching innovative sectoral partnerships and new funding to support these, with the aim of reshaping every sector of the economy at the scale necessary to deliver a net-zero future.

Despite significant headway on several fronts, national climate and financing commitments still fell far short of what is needed to come to grips with the climate challenge.

Here’s a summary of where things landed at COP26:

Did Countries Commit to Deep 2030 Emissions Cuts and Agree to a Process that Could Keep the 1.5 Degrees C Goal Alive?

“Not nearly enough” to the first question, “yes” to the second.

By the end of COP26, 151 countries had submitted new climate plans (known as nationally determined contributions, or NDCs) to slash their emissions by 2030. To keep the goal of limiting temperature rise to 1.5 degrees C within reach, we need to cut global emissions in half by the end of this decade. In contrast, the United Nations calculates that these plans, as they stand, put the world on track for 2.5 degrees C of warming by the end of the century. That is better than the 4 degrees C trajectory the world was on before the Paris Agreement was struck, but still extremely dangerous.

If you take into account countries’ commitments to reach net-zero emissions by around mid-century, analysis shows temperature rise could be kept to around 1.8 or 1.9 degrees C. But some major emitters’ 2030 targets are so weak (particularly those from Australia, China, Saudi Arabia, Brazil and Russia) that they don’t offer credible pathways to achieve their net-zero targets. This indicates a major “credibility gap” between the 2.5 degrees C-aligned 2030 targets and nations’ net-zero targets. To fix this problem, these countries’ must strengthen their 2030 emissions reduction targets to at least align with their net-zero commitments.

This is where the COP26 agreement comes in. The Glasgow decision calls on countries to “revisit and strengthen” their 2030 targets by the end of 2022 to align them with the Paris Agreement’s temperature goals. It also asks all countries that have not yet done so to submit long-term strategies to 2050, aiming for a just transition to net-zero emissions around mid-century. Together, stronger NDCs and long-term strategies should help align the net-zero and 2030 targets, as well as ramping up ambition. Elsewhere, the COP26 decision says that countries “resolve to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 degrees C,” which gives this lower temperature threshold even greater emphasis than in the Paris Agreement.

In addition, the pact asks nations to consider further actions to curb potent non-CO2 gases, such as methane, and includes language emphasizing the need to “phase down unabated coal” and “phase out fossil fuel subsidies.” This marked the first time negotiators have explicitly referenced shifting away from coal and phasing out fossil fuel subsidies in COP decision text.

And lastly, this COP finally recognized the importance of nature for both reducing emissions and building resilience to the impacts of climate change, both in the formal text and also through a raft of initiatives announced on the sidelines.

So, in the end, diplomats managed to keep hopes of limiting temperature rise to 1.5 degrees C alive, but just barely. Once we see major emitters’ new climate targets by the end of 2022, we will have a much better idea of whether we will be able to avoid breaching that temperature threshold — and if we do breach it, by how much.

Did Developing Countries Get the Finance and Support They Need?

In 2009, rich nations committed to mobilize $100 billion a year by 2020 and through 2025 to support climate efforts in developing countries. In the Glasgow Climate Pact, it was noted “with deep regret” that developed countries failed to meet that goal in 2020 (recent OECD estimates show that total climate finance reached $79.6 billion in 2019). The COP26 outcome made it clear that these countries are still on the hook to fulfill this goal as soon as possible, and stipulates that those countries must report on their progress.

Countries also agreed to a robust process to develop a new, larger climate finance goal to go into effect after 2025. They identified a wide range of options to ensure an inclusive and robust technical process to develop this new goal, and established an Ad Hoc Work Programme to convene technical experts and ministers to flesh out the details. The post-2025 climate finance goal is expected to be set by 2024.

Developed countries also agreed to at least double funding for adaptation by 2025, which would amount to at least $40 billion. This is a significant milestone to address the persisting imbalance between funding for mitigation and adaptation efforts; adaptation finance currently amounts to only a quarter of total climate finance, while needs to adapt to the increasing impacts of the climate crisis continue to grow.

The Adaptation Fund reached unprecedented levels of contributions, with new pledges for $356 million that represent almost three times its mobilization target for 2022. The Least Developed Countries Fund, which supports climate change adaptation in the world’s least developed countries, also received a record $413 million in new contributions. Although more money is needed to help developing countries increase their resilience to the effects of climate change, this progress was warmly welcomed by developing countries in Glasgow.

These countries also came to Glasgow hoping to create a clear plan to develop guidance on the collective assessment of progress toward the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA), a key component of the Paris Agreement that aims to strengthen resilience and reduce vulnerability to climate impacts. COP26 adopted the Glasgow-Sharm el-Sheikh work programme for the GGA. This will take place between 2022 and 2024 — to help improve assessment of progress toward the adaptation goal and enable its implementation — through regular workshops and work on methodologies to assess progress.

COP26 also took steps to help developing countries access good quality finance options. For example, encouraging multilateral institutions to further consider the links between climate vulnerabilities and the need for concessional financial resources for developing countries — such as securing grants rather than loans to avoid increasing their debt burden.

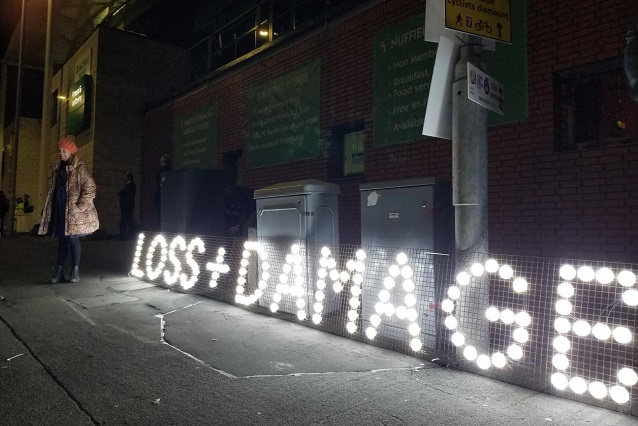

What Happened on “Loss and Damage”?

COP26 finally put the critical issue of loss and damage squarely on the main stage. Climate change is already causing devastating losses of lives, land and livelihoods. Some damages are permanent — from communities that are wiped out, to islands disappearing beneath the waves, to water resources that are drying up.

A number of climate-vulnerable countries advocated for COP26 to create a new finance facility dedicated to loss and damage, but that faced pushback by developed nations such as the United States. Instead, countries landed on creating a new dialogue dedicated to discussing possible arrangements for loss and damage funding. While this is grossly insufficient, it does offer space to develop concrete solutions that can lead to more progress on financing in the years ahead — which is a first for the COP discussions.

Financial pledges from Scotland and Wallonia (Belgium) — £2 million ($2.6 million) and EUR 1 million ($1.1 million), respectively — to address loss and damage were the first of their kind and very welcome, as was a similar commitment by various philanthropies. These helped cut through the political debate and put responsibility for finance for loss and damage firmly on the table.

Countries also agreed to operationalize and fund the Santiago Network on Loss and Damage, established at COP25 in Madrid, and to catalyze the technical assistance developing countries need to address loss and damage in a robust and effective manner.

Loss and damage is likely to be one of the bigger issues leading up to the COP27 summit in Egypt next year.

Did Negotiators Agree to Rules that Maintain the Integrity and Ambition of the Paris Agreement?

Many of the rules underpinning how the Paris Agreement will be implemented were adopted in 2018. However, decisions on a few outstanding issues have remained on the table since then, with important implications for pursuing climate ambition. These last issues were resolved at COP26, mostly for the better.

Here’s what negotiators decided on three important topics:

International Carbon Markets. After five years of negotiations, the world’s governments settled on the rules for the global carbon market under the Paris Agreement’s Article 6. One of the most contentious issues in recent years, the negotiations tried to balance finally reaching agreement on the rules while ensuring they didn’t undermine climate ambition, but instead maintained environmental and social integrity. Ultimately, negotiators agreed to avoid double-counting, in which more than one country could claim the same emissions reductions as counting toward their own climate commitments. This is critical to make real progress on reducing emissions. Countries also decided that 5% of proceeds must go toward funding adaptation under traditional market mechanisms (Article 6.4), though under bilateral trading of credits between countries (Article 6.2) contributing funds toward adaptation was only “strongly encouraged,” which may reduce this potentially secure source of finance for adaptation.

Unfortunately, countries decided they would allow the carry-over of old carbon credits generated since 2013 under the clean development mechanism of the Kyoto Protocol to help meet climate commitments of the Paris Agreement. At COP27, it is crucial that negotiators put stringent guidelines in place to ensure any of these older credits that are allowed to be used represent real emissions reductions, not just “hot air.”

Common Time Frames. In Glasgow, countries were encouraged to use common timeframes for their national climate commitments. This means that new NDCs that countries put forward in 2025 should have an end-date of 2035, in 2030 they will put forward commitments with a 2040 end-date, and so on. Aligning NDC targets’ dates around five-year cycles will hopefully help spur ambition and action in the near term, facilitate better understanding of global progress, ensure countries take action over the same time period, and keep pace with the Paris Agreement’s five-year cycle to strengthen their plans. The use of the term “encouraged,” rather than stronger language, may however weaken the impact of this decision.

Transparency. In Glasgow, all countries agreed to submit information about their emissions and financial, technological and capacity-building support using a common and standardized set of formats and tables. This will make reporting more transparent, consistent and comparable. This is a boon for the global community to better hold countries accountable for what they say they will do.

What Developments Outside the Negotiations Were the Most Significant?

Many significant announcements were made outside the negotiations throughout the two-week long summit. The first two days featured over 100 high-level announcements during the “World Leaders Summit” including a bold commitment from India to reach net-zero emissions by 2070 that is backed up with near-term targets (including ambitious renewable energy targets for 2030), 109 countries signing up to the Global Methane Pledge to slash emissions by 30% by 2030, and a pledge by 141 countries (as of November 10) to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030 (backed by $18 billion in funding, including $1.7 billion dedicated to support indigenous peoples).

In addition, the United Kingdom announced the Glasgow Breakthroughs, a set of global targets meant to dramatically accelerate the innovation and use of clean technologies in five emissions-heavy sectors: power, road transport, steel, hydrogen and agriculture. Read our overview of the World Leaders Summit for a more complete summary.

A group of 46 countries, including the U.K., Canada, Poland and Vietnam, made commitments to phase out domestic coal, while a further 29 countries including the U.K., Canada, Germany and Italy committed to end new direct international public support for unabated fossil fuels by the end of 2022 and redirect this investment to clean energy. The Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance, led by Costa Rica and Denmark — with core members France, Greenland, Ireland, Quebec, Sweden and Wales — pledged to end new licensing rounds for oil and gas exploration and production and set an end date that is aligned with Paris Agreement objectives.

Efforts were also made to scale up solar investment with the launch of a new Solar Investment Action Agenda by WRI, the International Solar Alliance (ISA) and Bloomberg Philanthropies that identifies high-impact opportunities to speed up investment and reach ISA’s goal of mobilizing $1 trillion in solar investment by 2030. And the U.S. became the fifteenth nation to join the High-Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy which commits its members to sustainably manage 100% of their countries’ national waters.

Non-state actors including investors, businesses, cities and subnational regions also joined collective action initiatives aimed at driving economic transformation. Over 2,000 companies have now committed to develop science-based targets for reducing their emissions, and new guidance for companies to set credible net-zero targets for corporates was released just ahead of COP26. Guidance for robust target-setting for net-zero claims in the finance sector are still under development.

Over 400 financial firms which control over $130 trillion in assets committed to aligning their portfolios to net-zero by 2030. This new alliance makes clear that banks, asset managers and asset owners fully recognize the business case for climate action and the significant risks of investing in the high-carbon, polluting economy of that past. The challenge now is for these institutions to scale up action at the pace and scale necessary according to a science-based pathway, set intermediate targets that align with their net-zero goals, and transparently report on their progress.

Over 1,000 cities and local governments joined the Cities Race to Zero to raise climate action to limit global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees C. And around 41 cities, 34 countries and 11 major automakers agreed to work toward selling only zero-emission vehicles globally by 2040, and by no later than 2035 in leading markets.

To help hold businesses and others accountable for achieving their net-zero goals, UN Secretary-General António Guterres announced he is creating a high-level expert group that will establish clear standards to measure and assess these commitments.

Where Do We Go from Here?

In a time marked by uncertainty, mistrust and escalating climate impacts, COP26 has affirmed just how essential collective global action is to address the climate crisis. While we are not yet on track, the progress made over the last year and at the climate summit offered bright spots and a strong foundation to build upon. This progress also demonstrates that the Paris Agreement mechanisms to strengthen ambition and finance are working, albeit imperfectly and not yet at the pace we need.

In the year ahead, major emitters need to ramp up their 2030 emissions reduction targets to align with 1.5 degrees C, more robust approaches are needed to hold all actors accountable for the many commitments made in Glasgow, and much more attention is needed on how to meet the urgent needs of climate-vulnerable countries to help them deal with climate impacts and transition to net-zero economies. The Glasgow Climate Pact outlines the key steps to do so. But it is only once this is achieved that we will truly have a shot at reaching the 1.5 degrees C goal and building a safer and more just future for us all.

This article was originally published on WRI’s Insights.

Helen Mountford is the Vice President for Climate and Economics at World Resources Institute.

David Waskow is the Director of the International Climate Initiative at World Resources Institute.

Lorena González is Senior Associate for UN Climate Finance at World Resources Institute’s Finance Center.

Chirag Gajjar is Head of Subnational Climate Action for the Climate Program at WRI India.

Nathan Cogswell is Research Associate for International Climate Action at World Resources Institute.

Mima Holt is Research Associate for International Climate Action at World Resources Institute.

Taryn Fransen is a Senior Fellow with the Global Climate Program at World Resources Institute.

Molly Bergen is Communications Manager for the Climate Program at World Resources Institute.

Rhys Gerholdt is the Director of Communications & Media Strategy for the Climate Program at World Resources Institute.