The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), composed of hundreds of the world’s leading scientists, puts considerable weight on urban climate action in developing pathways towards sustainable futures. The 6th Assessment Report of the IPCC recognizes that urban areas present opportunities for significant greenhouse gas emission reductions. This includes possibilities for shifts in infrastructure and urban form, clean electrification, fostering carbon sinks, and facilitating lifestyle changes that may deliver net-zero emissions.

Yet all these promises depend largely on the ability of actors in cities, whether local governments or other state and non-state institutions and individuals, to actually generate large-scale change. This involves mobilizing collective wills and entrepreneurial imperatives towards breaking the status quo, and doing so without further exacerbating inequality and vulnerability among already heavily impacted groups. The contribution of Working Group II (on impacts, adaptation and vulnerability) highlights the close relationship between urbanization, social inequality and vulnerabilities to climate change risks.

In a recent article in WIREs Climate Change, we identify two waves of thought in urban climate governance and perhaps a third that is now emerging under the shadow of a climate breakdown. The crucial question now being re-centered is simply: are we changing, and will that change be sufficient?

Optimism, Pragmatism and Beyond

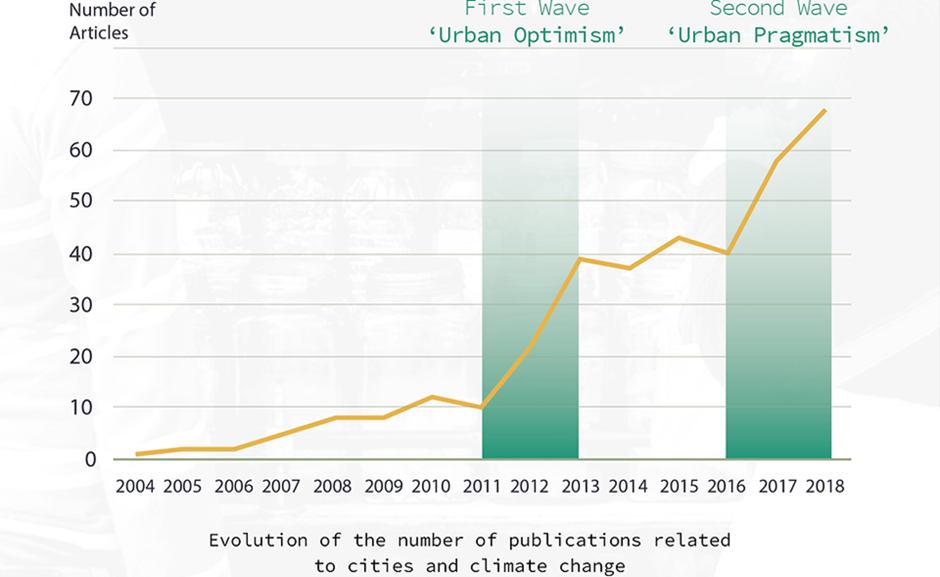

We conducted a systematic literature review of 383 articles that present social sciences analyses of climate change action in urban areas. From this, we identified two moments of acceleration.

The first wave, “Urban Optimism,” took off around 2011 and unfolded in parallel with the rise of the urban age in global sustainable development agendas. This wave portrayed cities as an alternative site of climate action in response to the crumbling international climate regime, following the failure of negotiations at the 2009 UNFCCC Conference of Parties in Copenhagen. During these years, research on urban climate action documented incentives to act on climate change in cities and elevated transnational city networks as an exciting new phenomenon in global climate politics.

However, around 2015, a new way of thinking around climate change emerged. We call this wave “Urban Pragmatism” because of its emphasis on quantitative assessments of effectiveness of existing institutions and policies for urban climate governance. This wave also questions the equity and justice impacts of these interventions.

The IPCC Working Group II report reflects this wave of pragmatism with its emphasis on maladaptation – the revelation that adaptation interventions may in fact have negative impacts on the resilience of populations. Examples of maladaptation in urban environments, including climate gentrification and the destruction of natural urban ecosystems, abound.

Through both waves, the discourse largely entrenched around concepts of efficiency, integration, and mechanisms that enable stakeholder participation, indicators which have to a certain extent come to define “good governance.”

Examining the elements of difference and continuity between the two waves helps characterize the current moment of urban climate thought. At the moment, there is a growing interest in themes that were part of the climate debate during previous moments of acceleration, including nature-based solutions, poverty and informality, and the possibilities of transformation. In addition, there is an even stronger emphasis on the “hows” of urban climate action and the mechanisms that facilitate its implementation, including collaboration among stakeholders and levels of action, integration across sectors, and the establishment of long-term objectives and monitoring.

We identify four elements that are now shaping urban climate thought in unexpected ways:

The Politics of Crisis

The adoption of climate emergency declarations by local governments signals the arrival of a new discourse of climate action in the institutional sphere. Debates on urgency, crisis and emergency translate into local politics through the advocacy of green movements, party politics and by expanding existing commitments to environmental action at the local level.

This new discourse has so far not reconfigured the processes or tools of municipal climate governance, but it may be linked with increasing polarization of the debate. Polarization entails many risks, not least the return of fantasies of solving climate change with a single solution, as shown in recent attempts to legitimize outlandish carbon sequestration and planetary monitoring technologies.

A Focus on Systems Change

Among researchers, practitioners and funders, there is a stronger concern with how to realize systemic governance strategies in practice. It is clearer that sectoral interventions are no longer enough to realize systemic and transformative action; what is needed is programs that consider the city from a systems perspective.

The systems perspective is, of course, not new. What is new is its resurgence – perhaps nigh dominance – in the climate debate. The report of the Working Group III of the 6th Assessment Report, for example, focuses on “urban systems” as the entry point for urban climate interventions. While the systems perspective is welcome, there has not been a serious examination of what it leaves behind.

From Justice to Intersectionality

The justice and equity agenda has moved towards a concern with how to embed intersectionality and allied feminist perspectives, recognizing that the inequities that people experience are not a function of a given identity but of the position that an individual occupies within a given context where multiple forms of oppression overlap.

This has generated an interest in the forms of knowledge that enable challenging those systems of oppression and questioning the deficits of credibility that individuals and social groups suffer because of their social position. At the IPCC, for example, there has been a strong debate about the need to move away from extractive approaches that harvest indigenous knowledge as a resource and to instead focus on establishing equitable knowledge-making partnerships with indigenous knowledge holders themselves, who must be recognized as authors in their own right.

Adaptation Over Mitigation

The increasing concern with the impacts of climate change mean that we are seeing a shift of emphasis towards adaptation, particularly among local governments and other urban governance bodies that see themselves as having to guarantee the safety of their populations. However, the report of the Working Group II to the 6th Assessment Report emphasizes that even marginal increases in global average temperatures reduce collective capacities to adapt to climate impacts. Urban climate action emerges as a multi-dimensional space of action in which the actions to deliver adaptation and mitigation are closely interlinked.

Shaping the Third Wave

Local climate action continues to be a source of hope in an increasingly splintered international environment and growing signs of climate breakdown. However, the past two decades of growing urgency around climate change have catalyzed a search for universal solutions that paradoxically may have diverted attention from the material realities and the very individuals that ultimately join and drive climate actions. How do we center those individuals and unique contexts, while taking the lessons from the eras of urban optimism and pragmatism?

There are opportunities to link the urgent need to focus on the “how” to this valuable literature – to exercise caution in the face of technological fantasies, for example, and to consider systemic change as a process of joining up problems (e.g., what are the equity impacts of transport interventions across sectors?) rather than the external imposition of comprehensive master plans. A nascent body of feminist, queer and anti-racist work on climate justice points towards alternatives for the delivery of fairer, more inclusive and safer urban futures in the Anthropocene.

Special thanks to Anne Maassen for her contributions to this article.

The project leading to this publication (LOACT) received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme, grant agreement no. 804051.

Linda K Westman is a Research Associate at the Urban Institute at the University of Sheffield.

Vanesa Castán Broto is Professor of Climate Urbanism at the Urban Institute at the University of Sheffield and the Principal Investigator of the LOACT Project.