Cities across the world are stepping up on climate change. Las Vegas’ new city hall comes dressed for the occasion with solar panels. Photo by pony rojo/Flickr

Cities are currently both climate-culprit and climate-victim. They are already responsible for 70 percent of global energy-related greenhouse gas emissions and 65 percent of global energy demand; they could easily account for more than three-quarters of electricity use by 2030. Cities in emerging economies, where 95 percent of population growth to 2030 and beyond will occur, will account for 70 percent of global growth in energy use through 2030.

But cities can also become climate-solvers. Cities as they are now will not pull us out of the climate crisis. But since 75 percent of the urban infrastructure that will exist by mid-century hasn’t been built yet, we have a huge opportunity to shape more resource-efficient cities to avoid the worst effects of climate change and that will also make us wealthier, healthier and more productive.

Investments in low-carbon city projects have significant benefits for urban and rural citizens alike. A seminal study by the New Climate Economy found that $1 trillion spent per year by cities on 11 types of low carbon projects would produce $17 trillion in net present financial value through 2050, just from the direct energy savings alone. A follow-on research review found that the economic and social benefits of those investments, such a improvements in citizen health, jobs generated, poverty and inequality eliminated, were many times greater even than the $17 trillion value. As just one example, health benefits of improved heating and insulation can be more than 10 times the value of energy savings.

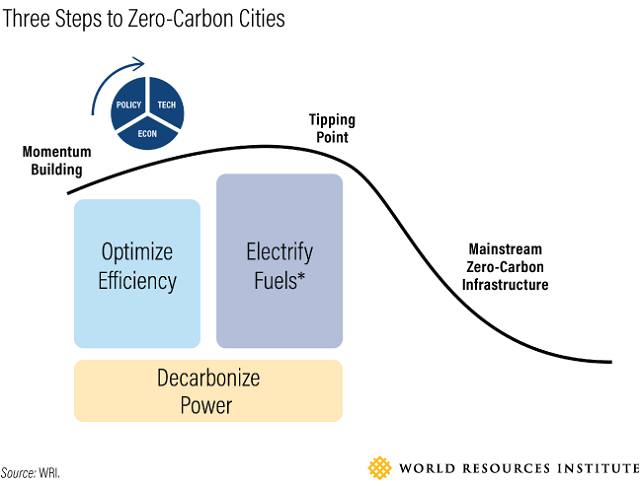

How do we do it? The good news is, it’s increasingly clear that cities need focus their brainpower on three things:

- Optimize: Make urban energy use more efficient across all sectors–particularly in buildings and transportation

- Electrify: Switch from fossil fuels to electricity for all transportation and some buildings

- Decarbonize: Simultaneously, cities should incentivize a transition to clean, zero-carbon energy sources for producing electricity, both distributed, like rooftop solar, and centralized, like wind farms.

Momentum is building across cities for adoption of these transitions. Changing technology and economics are making these options more attractive, “pulling” cities in this direction. Meanwhile, policies that encourage or require these three transitions are acting as a “push.” In brief:

Optimize: Energy efficiency is still the best option because it is the cheapest. Rapid market adoption of innovative technologies and practices, like LED lighting and regular, but still too-slow, turnover of outdated equipment, continue to improve efficiency.

Electrify: Electrification is happening across transportation, buildings and even heavy industry. While not appropriate in all circumstances, electrification is assumed under scenarios for limiting climate change to 2 degrees. And it has a myriad of non-climate benefits, from reduced noise and air pollution to more reliable pricing and supply. As the cost curves drop for renewables and storage, electrification will further accelerate.

Decarbonize: Recent breakthroughs in generation, storage, energy management and electric vehicles make a shift to clean electricity possible for nearly all uses. They also make it feasible for cities to optimize their energy loads by time-of-day, and by extension, for policy makers and utilities to shift demand for electricity to times when it’s cleanest – that is, when the wind blows and the sun shines. Incredible drops in the unit costs of batteries, wind turbines and solar cells make it impossible to ignore the cost savings and improved service that come from upgrading.

Who Can Act?

Mayors appear to be motivated, at least on paper. Seven thousand municipalities have committed publicly to climate action plans and targets. In the U.S., though climate action has become highly partisan, many more mayors (84 percent) believe climate change to be the result of human activities than the general public (68 percent), and 66 percent say cities should take action even if doing so requires financial costs.

City departments have a plethora of policy tools at their disposal to optimize and electrify their own assets as well as those of their residents and local industry. Cities such as Bogotá have upgraded their entire country’s policies on building energy codes. Cities can also use their buying power to spur higher-quality services (as in the emerging preference for contracting for electric vehicles in Latin America). Cities are also issuing campaigns or challenges to encourage new action by private sector players large and small (such as TheCityFix Labs in India, in which energy start-ups receive guidance on how to scale their business to serve city-scale needs). Though cities must look to state and national governments for help cleaning up centralized power, they can independently decarbonize – and become more resilient – by turning to decentralized renewables like solar. (The national-city linkage is the subject of our Unlocking Climate Action blog series.)

With the “push” of policy and the “pull” of technology and economics, we will reach a tipping point beyond which zero-carbon urban infrastructure becomes the obvious choice, even for late adopters.

The money will necessarily come from not from the traditional coffers of municipal finance, but instead the $120 trillion in assets under management by private investors, coupled with concessionary finance to cushion differing risk tolerances.

The investment thesis for those funds? All together now: Optimize. Electrify. Decarbonize.

This blog was originally published on WRI’s Insights.

Emma Stewart is the Urban Efficiency & Climate Director at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.

Eric Mackres is a Building Efficiency Manager with WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.