In 2011, a flooded street in Thailand became a river, forcing some residents to use boats to travel. Photo by ebvImages/Flickr

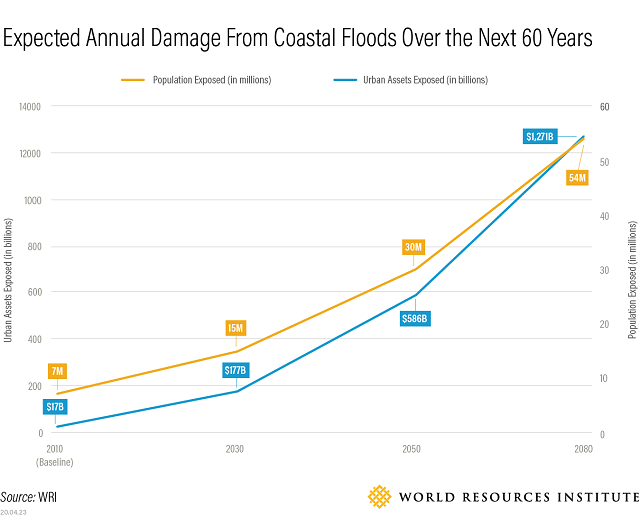

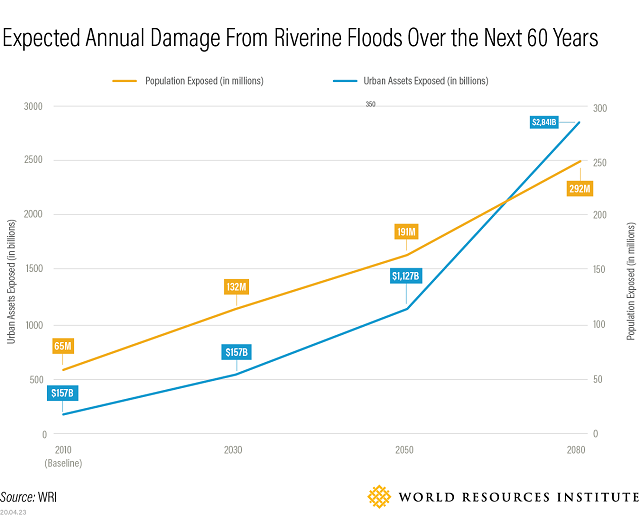

Flooding has already caused more than $1 trillion in losses globally since 1980, and the situation is poised to worsen: New analysis from WRI’s Aqueduct Floods finds that the number of people affected by floods will double worldwide by 2030.

According to data from the tool, which analyzes flood risks and solutions around the world, the number of people affected by riverine floods will rise from 65 million in 2010 to 132 million in 2030, and the number impacted by coastal flooding will increase from 7 million to 15 million. This is not only a threat to human lives, but to economies: The amount of urban property damaged by riverine floods will increase threefold – from $157 billion to $535 billion annually. Urban property damaged by coastal storm surge and sea level rise will increased tenfold – from $17 billion to $177 billion annually.

At a time when the COVID-19 pandemic is already threatening human health and economies, it’s clear that flood protection should be a priority investment for governments and other decision-makers.

Why Is Flood Risk Increasing?

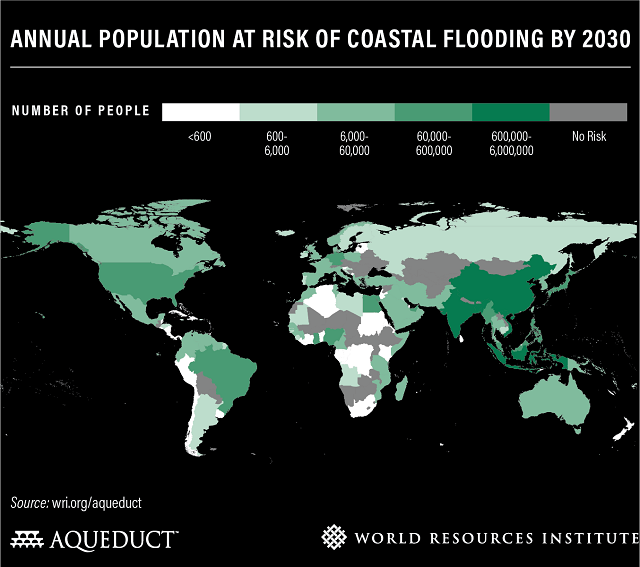

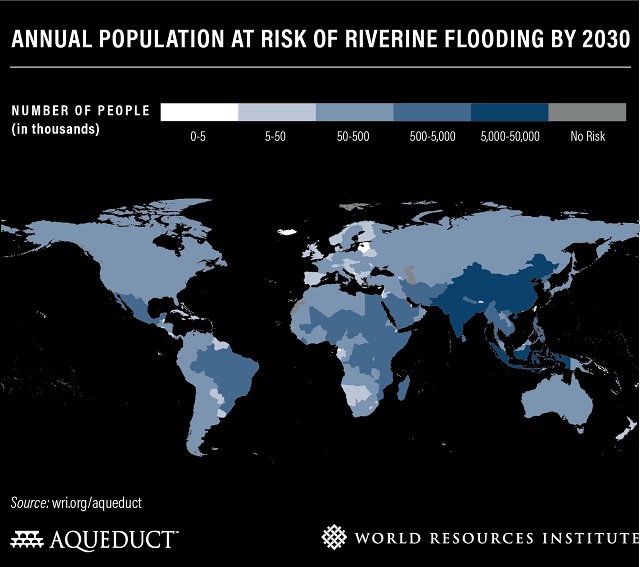

Flood risk is increasing dramatically due to heavier rains and storms fueled by climate change, socioeconomic factors such as population growth and increased development near coasts and rivers, and land subsidence driven by overdrawing groundwater. In places experiencing the worst flood risk, all three of these threats are converging, though the relative share of each varies by country.

India, Bangladesh and Indonesia, for example, have some of the largest populations affected by riverine and coastal floods each year. By 2030, these three countries will account for 44% of the world’s population annually affected by riverine floods, and 58% of population affected by coastal floods.

Even places you might not expect will see increased flood risk:

1. Climate Change Will Intensify Riverine and Coastal Floods.

Climate change will intensify rainfall and coastal storm surge in some parts of the world, putting more people in harm’s way. In Puerto Rico, for instance, climate change will be the number one driver of increased flood risk. By 2030, the expected annual population affected by riverine floods will double, while the expected annual damage to urban properties will increase $340 million. Heavier rains inland will drive around 51% of this increase.

The change to coastal communities will be even more pronounced. Currently, storm surge causes relatively little damage in Puerto Rico, thanks in part to strong flood-protection measures like dikes and levees. Existing coastal flood protection guards against 285-year floods (major floods with only a 0.35% probability of occurring). But with climate change causing more intense and frequent flooding, coastal flood protection could drop to only protect against 2-year floods (floods with up to a 50% probability of occurring). In other words, if left in its current state, Puerto Rico’s coastal flood protection will become effectively obsolete by 2030.

2. Socioeconomic Changes Will Put More People at Risk.

Growing populations and booming urban development in flood plains will increase both riverine and coastal flood risk in many countries. Even extremely water-stressed nations like Saudi Arabia will suffer. By 2030, 614,000 people in the country are expected to be affected by riverine floods annually – a tenfold increase from today’s risk – thanks largely to new development near rivers. Damage to urban property will increase by $1.6 billion annually.

Along the coast, 15,500 more people and $1.1 billion more in urban assets are expected to be affected annually by coastal floods by 2030. Urbanization accounts for 87% of this increased flood risk.

3. Sinking Land Will Increase the Risk of Floods.

Additionally, subsidence – sinking in coastal cities, largely caused by the overexploitation of groundwater – will put an additional 2 million people at risk of coastal flooding in 2030. The United States is projected to see an additional $16 billion in flood damages to urban property annually by 2030, with $4 billion caused by subsidence. This is more subsidence-driven flood risk than any other country. Subsidence’s role in future flooding is the most pronounced in the country’s west coast, where groundwater pumping is common to supplement scarce surface water supplies.

Investing in Flood Protection Infrastructure Can Save Lives, Create Jobs and Help Economies

Investing in protective measures like levees and dikes is not only important for safeguarding millions of people and their homes and businesses, but also to help grow economies. Aqueduct Floods allows decision-makers to assess the costs and benefits of adapting to riverine flood risk with flood protection infrastructure.

We found that, in many cases, flood protection measures offer a strong return on investment. For example, the three countries with the highest number of people affected by riverine flooding – India, Bangladesh and Indonesia – are all suitable candidates for riverine dikes. Every $1 spent on dike infrastructure in Bangladesh may result in $123 in avoided damages to urban property, when moving from the existing 3-year flood protection system to a 10-year flood protection system by 2050. This investment would reduce the likelihood of floods from 33% to 10%. In India, the investment is even more promising: Every $1 spent in India may result in $248 in avoided damages, when moving from the existing 11-year flood protection system to a 25-year flood protection system by 2050. In Indonesia, every $1 spent may result in $33 in avoided damages to urban property, when moving from the existing 10-year flood protection system to a 25-year flood protection system by 2050.

There are also job creation benefits. The costs for building flood defenses are not just a one-off capital investment; they require maintenance, which creates long-term jobs that stay in the local community. As governments look to rebuild their economies in the wake of COVID-19, investments in flood protection could be an important component of stimulus packages.

And built infrastructure like levees and dikes aren’t the only investments worth considering. Green infrastructure like mangroves, reefs and sand dunes act as natural buffers to coastal storms. Intact forests prevent erosion and can reduce landslides. Protecting and restoring this natural infrastructure offers flood protection and other benefits like water filtration and reduced greenhouse gas emissions.

Governments can pair natural ecosystems with more traditional gray infrastructure like embarkments and levees, called gray-green infrastructure. In the face of multiplying threats from climate change, gray-green infrastructure is a resilient, high-performing solution that also creates jobs.

Increasing investment in flood protection infrastructure and combining these methods will be necessary as climate change, socioeconomic growth and subsidence increase flood risk worldwide.

Aqueduct Floods is an online platform that measures and maps global flood risk. WRI co-developed this tool with Deltares, the Institute for Environmental Studies at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency and Utrecht University, with funding from the Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management and the World Bank. Like its predecessor, Aqueduct Global Flood Analyzer, this tool estimates current and future riverine flood risk to urban assets, GDP and population for every state, country and major river basin around the world, as well as in 120 select cities. The updated tool now includes coastal flood risk (including future impacts of sea level rise, subsidence and socioeconomic growth), existing flood protection levels per state, explorable inundation maps and the ability to assess the costs and benefits of adapting to riverine flood risk.

This blog was originally published on WRI’s Insights.

Samantha Kuzma is an Associate for the Water Program at World Resources Institute

Tianyi Luo is a Senior Manager with the Water Program’s Aqueduct Project at World Resources Institute.