Countries and cities need a variety of solutions, including renewable energy and healthy forests, to reach net-zero greenhouse gas emissions. Photo by David Grant/Flickr

The latest research is clear: To avoid the worst climate impacts, global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions will not only need to drop by half in the next 10 years, they will then have to reach net-zero around mid-century.

Recognizing this urgency, the UN Secretary General recently asked national leaders to come to the UN Climate Action Summit this September 2019 with announcements of targets for net-zero emissions by 2050. Several countries have already committed to do so, along with some states, cities and companies.

Here we explore what a net-zero target means, explain the science behind net-zero, and discuss which countries have already made such commitments.

1. What Does It Mean to Reach Net-Zero Emissions?

We will achieve net-zero emissions when any remaining human-caused GHG emissions are balanced out by removing GHGs from the atmosphere (a process known as carbon removal). First and foremost, human-caused emissions ‒ like those from fossil-fueled vehicles and factories ‒ should be reduced as close to zero as possible. Any remaining GHGs would be balanced with an equivalent amount of carbon removal, for example by restoring forests or through direct air capture and storage (DACS) technology. The concept of net-zero emissions is akin to “climate neutrality.”

2. When Does the World Need to Reach Net-Zero Emissions?

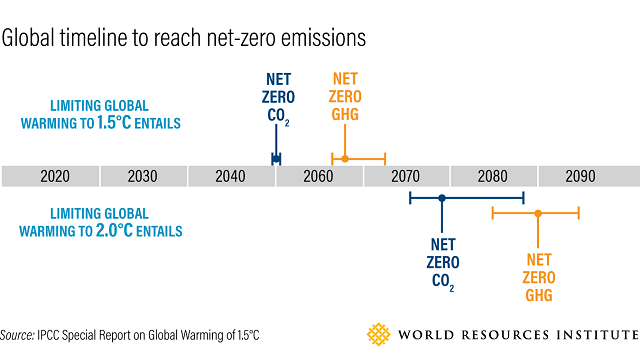

Under the Paris Agreement, countries agreed to limit warming well below 2 degrees C (3.6 degrees F) and ideally 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F). Climate impacts that are already unfolding around the world, even with only 1.1 degrees C (2 degrees F) of warming ‒ from melting ice to devastating heat waves and more intense storms ‒ show the urgency of minimizing temperature increase to no more than 1.5 degrees C. The latest science suggests that to meet the Paris Agreement’s temperature goals, the world will need to reach net-zero emissions on the following timelines:

- In scenarios that limit warming to 1.5 degrees C, carbon dioxide(CO2) reaches net-zero on average by 2050 (in scenarios with low or no overshoot) to 2052 (in scenarios that have high overshoot, in which temperature rise surpasses 1.5 degrees C for some time before being brought down). Total GHG emissions reach net-zero between 2063 and 2068.

- In 2 degrees C scenarios, CO2reaches net-zero on average by 2070 (in scenarios with a greater than 66% likelihood of limiting warming to 2 degrees C) to 2085 (50–66% likelihood). Total GHG emissions reach net-zero by the end of the century.

The Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5˚C, from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), finds that if the world reaches net-zero emissions one decade sooner, by 2040, the chance of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees C is considerably higher. The sooner emissions peak, and the lower they are at that point, the more realistic it is that we achieve net-zero in time. We would also need to rely less on carbon removal in the second half of the century.

Importantly, the time frame for reaching net-zero emissions differs significantly if one is referring to CO2 alone, or referring to all major GHGs (including methane, nitrous oxide, and “F gases” such as hydrofluorocarbons, commonly known as HFCs). For non-CO2 emissions, the net-zero date is later because some of these emissions ‒ such as methane from agricultural sources ‒ are considered somewhat more difficult to phase out. However, these gases will drive temperatures higher in the near-term, potentially pushing temperature change past the 1.5 degrees C threshold much earlier.

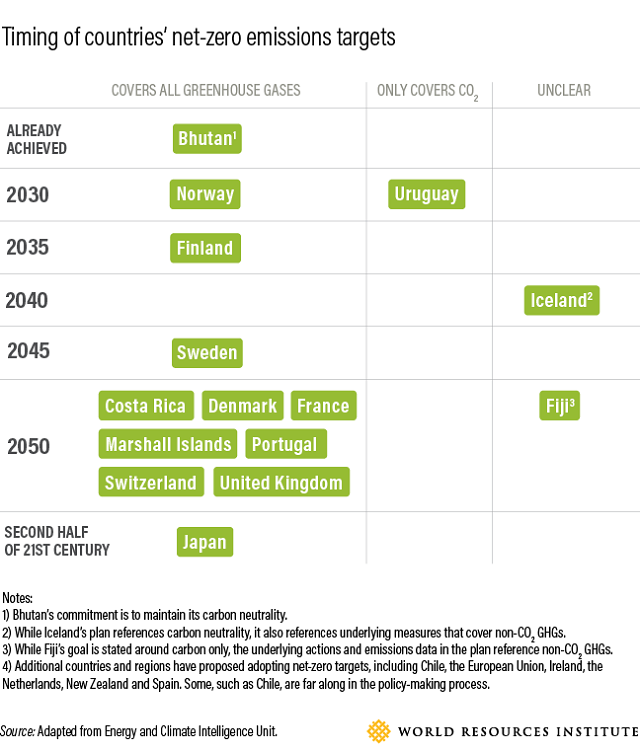

Because of this, it’s important for countries to specify whether their net-zero targets cover only CO2 or all major GHGs. A comprehensive net-zero emissions target would include all major GHGs, ensuring that non-CO2 gases are also reduced.

3. Do All Countries Need to Reach Net-Zero at the Same Time?

The timelines above are global averages. Because countries’ economies and stages of development vary widely, there is no one-size-fits-all timeline for individual countries. There are, however, hard physical limits to the total emissions the atmosphere can support while limiting global temperature increase to the agreed goals of the Paris Agreement. At the very least, major emitters (such as the United States, the European Union and China) should reach net-zero GHG emissions by 2050, or it will be hard for the math to work regardless of what other countries do. Ideally, major emitters will reach net-zero much earlier, given that the largest economies play an outsize role in determining the trajectory of global emissions.

4. How Many Countries Have Net-Zero Targets?

Fifteen countries have now adopted net-zero targets ‒ Bhutan, Costa Rica, Denmark, Fiji, Finland, France, Iceland, Japan, the Marshall Islands, Norway, Portugal, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and Uruguay. An updated list of announcements can be found here. While there are new announcements every month, the percentage of global emissions covered by some form of a net-zero target still hovers around 5%. Some of these targets are in law, and some are in other policy documents. Some net-zero targets have been incorporated directly into countries’ long-term, low-emissions development strategies, while other countries have adopted net-zero targets before submitting a long-term strategy.

Additional countries and regions have proposed adopting net-zero targets, including Chile, the European Union, Ireland, the Netherlands, New Zealand and Spain.

5. How Do We Achieve Net-Zero Emissions?

Policy, technology and behavior need to shift across the board. For example, in pathways to 1.5 degrees C, renewables are projected to supply 70-85% of electricity by 2050. Energy efficiency and fuel-switching measures are critical for transportation. Improving the efficiency of food production, changing dietary choices, halting deforestation, restoring degraded lands, and reducing food loss and waste also have significant potential to reduce emissions. It is critical that the structural and economic transition necessary to limit warming to 1.5 degrees C is approached in a just manner, especially for workers tied to high-carbon industries. The good news is that most of the technologies we need are available and they are increasingly cost-competitive with high-carbon alternatives. Markets are waking up to these opportunities and to the risks of a high-carbon economy, and shifting accordingly.

Additionally, investments will need to be made in carbon removal. The different pathways assessed by the IPCC to achieve 1.5 degrees C rely on different levels of carbon removal, but all rely on it to some extent. Removing CO2 from the atmosphere will be necessary to compensate for emissions from sectors in which reaching zero emissions is more difficult, such as aviation. Carbon removal can be achieved by several means, including land-based approaches (such as restoring forests and boosting soil uptake of carbon) and technological approaches (such as direct air capture and storage, or mineralization).

6. Does the Paris Agreement Commit Countries to Achieving Net-Zero Emissions?

In short, yes.

The Paris Agreement has a long-term goal of achieving “a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases in the second half of this century, on the basis of equity, and in the context of sustainable development and efforts to eradicate poverty.” The concept of balancing emissions and removals is akin to reaching net-zero emissions.

Coupled with the ultimate goal to limit warming well below 2 degrees C, and aiming for 1.5 degrees C, the Paris Agreement commits governments to sharply reduce emissions and ramp up efforts to reach net-zero emissions in time to avoid the worst consequences of climate change. The Paris Agreement framework also invites countries to submit long-term, low-emissions development strategies, which can be a vehicle for setting net-zero targets. Long-term strategies chart how countries aim to make such transitions.

In the spirit of the Paris Agreement, countries should come to the UN Climate Action Summit this month with commitments to create bold short- and long-term targets that align with a net-zero emissions future. This would send important signals to all levels of government, to the private sector, and to the public that leaders are betting on a safe and prosperous future, rather than one devastated by climate impacts.

This blog was originally published on WRI’s Insights.

Kelly Levin is a Senior Associate for the Climate Program at World Resources Institute.

Chantal Davis is an Intern for Long-Term Climate Strategies at World Resources Institute.