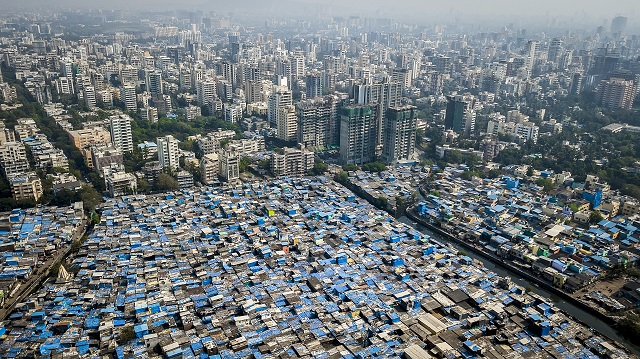

The juxtaposition of tarp-covered informal settlements and high-end developments in Mumbai makes urban inequities starkly visible. Photo by Johnny Miller/Unequal Scenes

Imagine Lagos, Nigeria, a city of 22 million. What was once a small coastal town just a few decades ago has exploded into a sprawling megacity spanning 452 square miles. Its rapid growth has stretched the city’s services impossibly thin: Less than 10 percent of people live in homes with sewer connections; less than 20 percent have access to tap water. Many houses are in slums and informal settlements at the city’s periphery.

Now picture Lagos twice as big.

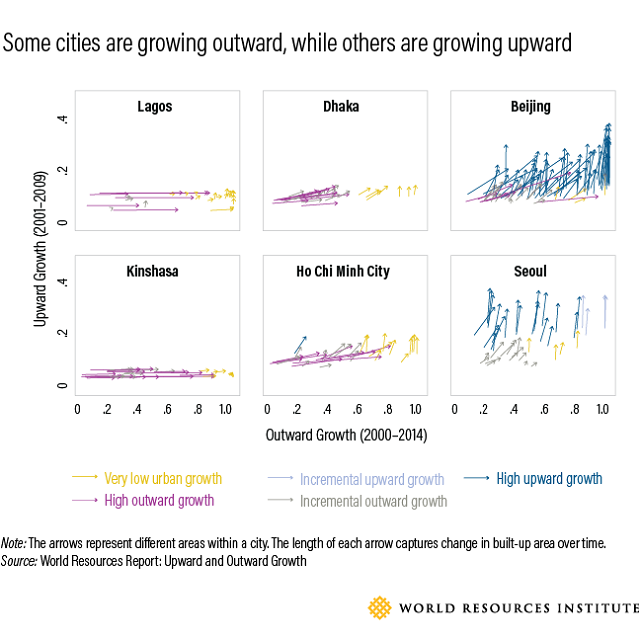

Lagos is one of many cities expected to grow exponentially over the next three decades, in both population and land area. Recent estimates show that urban land area could increase 80 percent globally between 2018 and 2030, assuming constant annual growth rates. When cities spread outward instead of upward, as Lagos has, it can worsen spatial inequalities and strain economies and natural resources.

Lagos, Nigeria, is expected to at least double its land area by 2050. Photo by Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung / Flickr

In our new World Resources Report paper, “Upward and Outward Growth: Managing Urban Expansion for More Equitable Cities in the Global South,” we analyzed growth patterns for 499 cities using remote sensing.

While cities growing vertically through taller buildings are located predominantly in wealthier cities in North America, Europe and East Asia, cities in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia are growing mainly outward. These cities have the fewest financial resources to manage their growth but are expected to hold more than 2 billion additional people by 2050. As we know from the latest UN data, just three countries – India, China and Nigeria – are expected to account for 35 percent of global urban population growth between 2018 and 2050. As these cities grow in population, continuing their unwieldy expansion outward could push them into crises.

The Consequences of Unmanaged Urban Expansion

Failure to properly manage expanding land area not only exacerbates urban inequality, it also contributes to greater economic and environmental risk for the city as a whole. From Mumbai to Mexico City, it is all-too-common to see crowded slums grow larger and denser next to unaffordable, often vacant, high-rise developments. As municipal service networks fail to keep pace with urban growth, resource-constrained cities tend to react to development trends instead of having land development agencies proactively plan for growth.

Some of the implications of this unmanaged growth include:

1. Greater Inequality: Like Lagos, many cities are already struggling with existing inequalities, inadequate service provision and stretched municipal capacities. Unmanaged land expansion exacerbates these struggles. Lower-income families typically move to a city’s periphery in search of affordable housing. Yet the further they get from the city center, the more difficult their lives can become. Families at a city’s edge will spend twice as much money and three times as much time commuting as families closer to jobs, schools and entertainment in the city center. As a city spreads outward, local agencies often struggle to provide water, sanitation and electricity. Citizens then have to rely on informal service provision – such as private water trucks and waste collectors that can charge up to 30 times more than city agencies – or go without these services, affecting their health and overall quality of life. Only the well-off can afford these coping strategies, leaving many urban residents under-served. Once these kinds of urban land development patterns begin, they have long-term effects on access to opportunities, productivity and quality of life.

2. Economic Stresses for the City as a Whole: Research shows that as cities expand outward and population densities decline, the municipal costs of providing public services increase. In Indian and African cities, services like paved roads, drainage and piped water drop off sharply just 5 kilometers (3 miles) from the city. The associated investments for new infrastructure and social costs of their deficit only keep climbing as new urban areas are added. Moreover, sprawl means more congestion, pollution and longer commutes. Dirty air, mostly driven by heavy use of private cars and trucks, creates immense social and economic costs, such as health impacts and crop damage. In Chengdu, China, the economic loss from transport-related air pollution tallied $3 billion in 2013.

3. Environmental Problems: Globally, the rate of urban land growth far outpaces population growth. This often comes at a cost to prime agricultural land, ecosystem services and biodiversity, which all contribute to food production and climate resilience.

Already, we are seeing some of the fastest-growing urban areas in low-elevation coastal zones, flood plains, biodiversity hotspots and water-stressed areas. Rampant development in these sensitive ecosystems can further strain natural resources and lead to disastrous flooding from seasonal monsoons in many South Asian cities. Unregulated well-digging in cities such as Mexico City, Bangalore and Jakarta, which are growing outward rapidly and have little piped water and high water stress, is causing whole neighborhoods to sink. It’s particularly troubling in Jakarta, where experts say that factoring in sea level rise, the city has only a decade to halt its sinking before millions of homes end up underwater.

Reining in Unmanaged Expansion

These impacts are compounded by the fact that most outward growth currently underway in Africa and South Asia is unplanned and informal, or in locations where existing urban land use regulations do not apply. Some of this expansion is outside of cities’ control, considering natural population increases and people migrating from rural to urban areas in search of economic opportunities. But other challenges are things cities can more proactively manage.

For example, distorted land markets can lead to speculative and fragmented development, where private landowners, real estate developers and corrupt public officials disproportionately benefit from rising land values. Weak planning, ineffective land-use regulations and certain market conditions are known to fuel expansion, relegating affordable housing to unserviced or poorly serviced locations at a city’s periphery. And haphazard conversion of farmland and absorption of peripheral villages result in informal settlements or slums that are disconnected from city services.

Though a daunting challenge, some cities are already using innovative approaches to prioritize accessibility and manage urban expansion. Cities in Mexico, Brazil and South Africa are directing new development to already well-serviced and connected areas, instead of spreading outwards. Cities in Colombia, South Korea and India have been incrementally adding new land in well-connected and serviced locations by partnering with public utilities and private companies to help with financing. Many cities are also working with communities in informal settlements to create affordable density with more flexible planning standards and upgrading efforts.

The impacts of land-use policy changes in a city can last for many decades. Cities in Africa and Asia have a choice: Start managing unsustainable outward expansion today, or see problems worsen tomorrow.

This blog was originally published on WRI’s Insights.

Jillian Du is a Research Assistant at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.

Anjali Mahendra is Director of Research at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.