São Paulo has established a direct metro connection between low- and high-income neighborhoods, saving many domestic workers significant commuting time. Photo by Diego Torres Silvestre/Flickr

Like workers in many other sectors, hundreds of thousands of domestic workers have been fired from their jobs around the world during the COVID-19 pandemic. But as economies have begun to reopen, many are returning to work, facing not only the health threat of contagion in public transit but extremely long commutes that were a challenge even before the pandemic.

Over the last four years, I conducted more than 180 interviews with domestic workers, public officials, experts and employers in Medellín and Bogotá, Colombia, to understand the unique difficulties faced by this huge sector of commuters. One in every four female wage workers in Latin America is a domestic worker, accounting for approximately 17 million people. In Bogotá alone there are around 150,000 domestic workers, and in Medellín about 54,000. Data from the domestic worker matching app HogarU for 2019 shows that the average time female domestic workers traveled for work each way was 86 minutes in Bogotá and 68 minutes in Medellín – 42% more than the average female worker.

One of the main challenges is the sheer amount of time domestic workers must spend in transit, in part because they often have different travel patterns than other commuters. Primarily planned around the commuting patterns of men, public transportation in both cities connects workers between the low-income periphery and the central business districts, where the highest number and concentration of formal jobs are located. However, many domestic workers find jobs in high-income residential areas that are not well connected to public transportation networks.

A clear solution would be to establish more direct routes between low- and high-income residential sites. But transport officials in both cities insisted to me that a direct line was not politically viable or financially sustainable.

In 2020, the Lee Schipper Memorial Scholarship gave me the chance to dig deeper in this mobility dynamic, expanding from qualitative data from Bogotá and Medellín to incorporate quantitative data from both cities and from São Paulo. To my surprise, I found in São Paulo what I had been looking for: direct metro lines between low- and high-income residential neighborhoods.

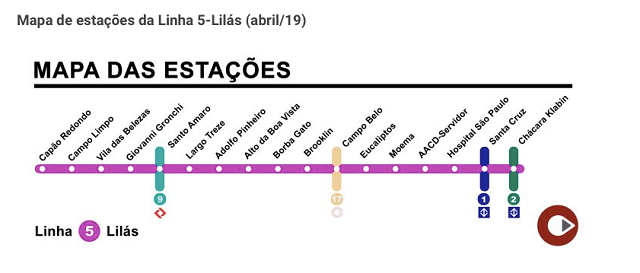

One of these lines is the Lilás. Construction of this metro line, located in a massive low-income area south of São Paulo, started in 1998 as part of the city’s Integrated Plan for Urban Mobility and began operating with five stations in 2002. These stations were initially only connected to the rest of the metro system by a commuter rail line. But in an interview I conducted with WRI’s Sergio Avelleda, former secretary of mobility and transport in São Paulo, he said Governor Mario Covas believed that starting the Lilás in this low-income area was the only way to ensure it was connected to the rest of the city. Avelleda also noted that it was also more financially viable to start the line in this area since the metro is elevated in these five stations, which is less costly than subterranean infrastructure.

Map of stations along the Lilás. Source: Metrô CPTM

Construction was restarted on the Lilás for an expansion in 2011, and the full line was inaugurated in 2019 when the Campo Belo station was opened. Now the line connects Capão Redondo and Campo Limpo, both low-income residential neighborhoods, with a number of high-income residential areas.

In interviews conducted with domestic workers living in Campo Limpo, they said the new line saved them significant commuting time. They do not need to go first to the central business district and then transfer to some other transport service to connect to the high-income residential neighborhoods where they work, as is the case in Bogotá and Medellín.

“Now I spend one hour and a half to go from my house because I take the metro in Campo Limpo Station to Brooklin,” domestic worker Lucia explained. “Before I used to take a metro, then a bus to get there, and then I walked. It used to take two hours. Now it is half an hour less, on that trip.” Another domestic worker, Claudia, said her one-way commute was reduced from two hours and a half to one hour and a half.

On the Lilás in São Paulo. Photo by Valentina Montoya-Robledo

More Latin American cities should consider direct public transport services that can better serve these women. Other types of workers like doormen and domestic nurses also stand to benefit from dramatically reduced commuting times from these kinds of integrated systems, whether through metro, bus, cable car or other transit connections. Bike-sharing systems could also reinforce these lines by helping with last-mile connectivity.

The example of the Lilás line in São Paulo should be replicated in cities with similar segregation patterns. In Medellín, a direct line between the wealthy area of El Poblado and the working-class neighborhoods of Buenos Aires, or in Bogotá between Usme and Rosales, would significantly improve the lives of domestic workers, for example. Shorter commuting times means more time to care for children, to rest, to study, and to engage with their communities and the wider city.

Planners and designers should reconsider the city as a dynamic and living organism, where every part is connected via public transportation systems. If we want mobility to be available to all residents and to reduce traffic jams and pollution, high-income neighborhoods cannot remain exclusionary and disconnected areas. All residents and all types of workers deserve equal access to efficient, safe and sustainable transport.

All names of domestic workers have been changed to protect their privacy.

Valentina Montoya-Robledo is a Doctor of Juridical Science from Harvard Law School and a 2020 Lee Schipper Scholarship Winner.