As our colleagues have covered previously, there are clear health and environmental benefits to adopting electric school buses instead of their diesel counterparts, which account for more than 90% of the U.S. school bus fleet and result in harmful exhaust and emissions that negatively affect students and their communities. However, school bus electrification is only one component of a safer and more sustainable school transportation system. Even if all 480,000 school buses in the United States were electrified overnight, that would only solve part of the problem created by school travel, as only one third of U.S. students travel to school on school buses.

While WRI’s Electric School Bus Initiative is focused chiefly on bringing more electric school buses to more districts, we also recognize the value of looking at the trip to and from school in a holistic way. Beyond the Electric School Bus Initiative, WRI also works on other related issues like road safety, active mobility and safe school zones across many geographies.

How Do Students Travel to and From School in the U.S.?

According to data from the National Household Travel Survey, conducted by the U.S. Department of Transportation, most students travel to school in private vehicles, and the share of students doing so has grown dramatically in recent decades. In 1969, only 16% of students traveled to school in private vehicles, but by 2017 that figure had more than tripled to 54%. At the same time, the share of students walking and biking to school has dropped precipitously, from 42% in 1969 to just 10% in 2017.

More students traveling to school in private vehicles instead of walking and biking results in more car trips, leading to higher levels of transportation-related emissions and greater traffic safety risks for students that walk and bike. It also means students lose out on the myriad benefits associated with active transportation, which include improved cardiovascular fitness and overall health, as well as a higher degree of alertness during school hours and even better grades. These benefits are particularly important when considering that the prevalence of childhood obesity in the U.S. has more than doubled in children and tripled in adolescents over the past three decades, reaching epidemic levels.

Why Are Fewer Students Walking and Biking?

One reason why fewer students are walking and biking to school in the U.S. is that students now tend to live farther from the schools they attend than in previous decades. For example, in 1969, the majority of students (52%) lived less than 2 miles from school, and only a third (33%) lived 3 miles or more from school. But by 2017, the median distance to school had reached 2.7 miles.

Several factors have contributed to this increase in home-to-school distance. School siting decisions have resulted in schools being located in less accessible areas farther from population centers for multiple reasons. For example, many states have funding formulas that favor construction of new schools over renovation of existing schools that may already be closer to where students live. The acreage of school sites has also increased over time as schools have begun providing more services, including cafeterias, libraries, science and computer labs, playgrounds, athletic fields, theaters, career and adult education facilities, and space for parking and driving children to school. In addition, the number of districts and schools has declined dramatically, as states and districts have pursued school consolidation to increase average enrollment and reduce costs.

Changes in school assignment and enrollment policies may play a role as well. Rather than simply assigning students to their neighborhood school, more school districts have open enrollment policies that allow families to choose from a larger number of schools. While research has shown that school location and distance are the primary factors affecting school choices, families with more options can consider additional factors, especially academic performance. When families prefer schools beyond their neighborhood, they must travel longer distances to reach those schools. This may be particularly challenging for low-income families that feel underserved by their neighborhood school but are less able to afford the additional costs of attending a school that is located farther away.

Longer home-to-school distances are not the only reason for large shares of students traveling to school by private vehicle. Students living within a mile of their school are unlikely to qualify for school bus service, but nonetheless we see that many choose not to walk or bike. As of 2017, a majority of students living 0.5-1 miles from school and a third of students living only 0.25-0.5 miles from school travel by private car.

Research has shown that decisions about walking and biking to school are strongly tied to parents’ concerns over traffic danger and pedestrian safety, especially for young children. For example, a national parent survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2005 found that, after school distance, traffic-related danger was the top barrier cited by parents as preventing their children from walking to school.

These concerns are increasingly justified, as walking and biking are becoming more dangerous in the United States (and elsewhere), due in large part to increasing vehicle speeds. According to data from the National Safety Council, the number of pedestrian fatalities in the U.S. increased 45% from 2010 to 2020, offsetting the progress made over the previous three decades. Bicyclist fatalities, meanwhile, increased an astonishing 75% from 2010 to 2020. For both pedestrians and bicyclists, the number of deaths in 2020 was higher than in 1990.

The U.S. is also lagging behind many international peers in road safety. Between 2010 and 2018, the U.S. experienced the largest percentage increase in pedestrian fatalities among 29 OECD countries, 24 of which saw decreases in pedestrian fatalities. Over the same period, the U.S. also experienced a larger percentage increase in cyclist fatalities than 25 OECD countries, 17 of which saw decreases.

What Can Be Done to Increase the Share of Students Walking and Biking?

School districts, cities, counties and states can increase walking and biking among students by investing in infrastructure, implementing programs and enacting policies that make schools safer and more accessible by active modes. Supporting these efforts is especially important for underserved communities. For example, there is a growing body of evidence showing that communities with larger low-income and minority populations experience higher crash rates. Research has also found that a substantial portion of traffic injuries in these communities can be explained by differences in their roadway environments, meaning they may benefit the most from policy and design changes.

Invest in safety infrastructure around schools

Expanding and improving dedicated bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure is critical to making walking and biking viable modes of travel, especially for children. This infrastructure includes a number of elements geared towards improving safety and accessibility for pedestrians and cyclists, such as bike lanes, curb extensions, sidewalks, raised pedestrian crossings, shorter blocks and narrower lanes.

A good example of such measures is Fair Haven, New Jersey, which for the past 18 years has closed a main street connecting an elementary and middle school to cars during arrival and dismissal of students. Since the school district does not provide bus service, this measure promoting safe, active commutes to school is especially important. The initiative is supported by the New Jersey Department of Transportation’s Safe Routes program, which aims to work with school districts to prioritize active modes of travel to and from school.

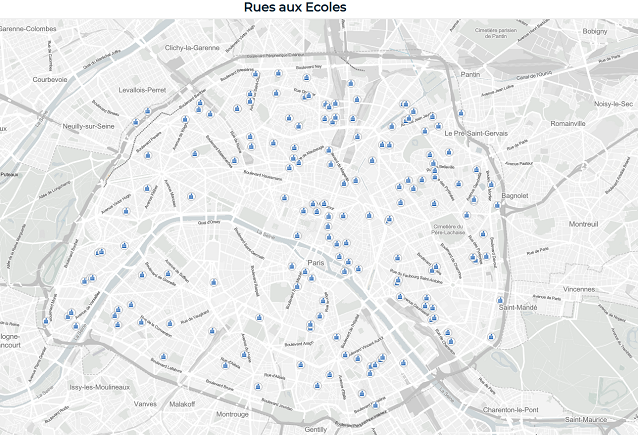

Another recent example of such changes is the city of Paris’ Rues aux Écoles (“Streets to Schools”) program. Starting in 2020, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, the city pedestrianized 114 streets around pre-K and elementary schools, bringing Paris’ total number of these “streets to school” to 169. The city used elements such as planters, signage and posts to quickly (and cheaply) transform the use of these streets to promote safe and socially distant walking and biking to school.

Implement programs that promote walking and biking to school

Organizations like the national Safe Routes to School Partnership in the U.S. are engaging students and community members to increase their awareness of and enthusiasm for walking and biking. They provide people with the skills to walk and bike safely and teach them about the broad range of transportation choices available. Successful promotional efforts have also used bike sharing and loan programs, public awareness campaigns, outreach to press and community leaders, stepped up traffic enforcement in the vicinity of schools, and volunteer trainings.

Places like Bogotá have implemented similar programs successfully. The al Colegio en Bici (“to School by Bike”) program, which has been operating since 2013, loans bicycles to students during the school year. Additionally, adult guides lead daily caravans to and from schools, and the program provides basic bike maintenance training for students. Al Colegio en Bici is complemented by the Ciempiés (“Centipede”) program, a “walking school bus” program where groups of students walk to school together with adult supervision. This year, these two initiatives are expected to benefit over 12,000 students, mainly from the most impoverished areas of the city.

Enact policies that support safe conditions and reduce home-to-school distance

Beyond the programs and infrastructure described above, more holistic policy changes are needed to improve student safety and change the way communities are structured. There are multiple organizations working at the national level in the U.S. to help communities develop policies focused on pedestrian and cyclist safety.

For example, the National Complete Streets Coalition promotes the development and implementation of policies that safely integrate multiple modes of transport into the planning, design, construction, operation and maintenance of transportation networks. More than 1,600 “complete streets” policies have been passed in the U.S., including those adopted by 35 state governments, the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico.

Another example is the Vision Zero Network, a collaborative campaign that helps communities reach the goal of eliminating all traffic fatalities and severe injuries. Currently more than 45 communities have committed to Vision Zero.

Collectively, these infrastructure, outreach and policy measures have been demonstrated to be effective at increasing the share of students walking and biking to school. Communities can also consider measures that reduce overall vehicle speeds, especially around schools, which have been shown to reduce injuries and deaths from road traffic crashes. Finally, states and districts can use tools like the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Smart School Siting Tool to learn more about the connections between school location and community development and explore ways to reduce home-to-school distance and increase accessibility by active transportation modes. The path will be unique in each community, but – as with the transition to electric school buses – collaboration across sectors is a must to create sustainable, equitable and safe transportation for all students.

Phillip Burgoyne-Allen is an Associate with the Electric School Bus Initiative at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.

Sebastian Castellanos is the Research Lead for NUMO, the New Urban Mobility alliance, and a Senior Research Associate at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.