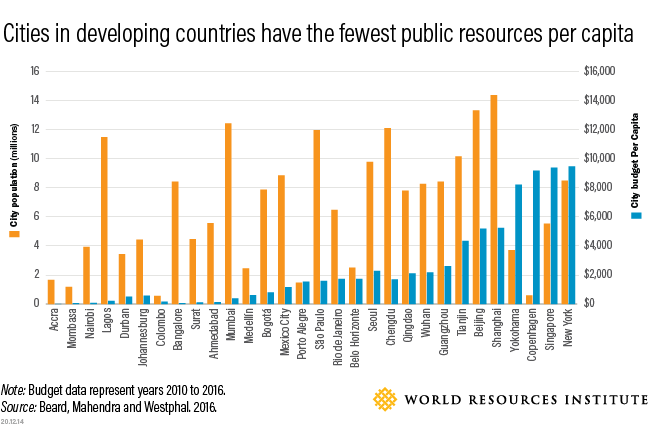

Some of the fastest growing cities in developing countries like India, Brazil and Ethiopia are strapped for cash. These cities often struggle to provide basic infrastructure and services for a growing population, leading to widespread inequalities. Up to 70% of residents in developing cities lack access to one or more core service, such as housing, water and sanitation, energy or transportation.

One financial tool that can help cities generate public revenue to address inequalities and promote inclusive development is land value capture.

What Is Land Value Capture?

Land value capture is a financing tool that allows local governments to charge fees and taxes to developers and property owners and raise revenue that can then be reinvested into community and city services. It is a technical term for a simple idea that’s applicable to cities of all types and it is especially important and underutilized in developing cities. This tool has been more commonly used in developed cities, but developing cities have much to gain if they can implement land value capture effectively.

As an urban area grows and develops, the price or value of land generally goes up — especially when the government invests in public infrastructure or implements zoning changes and incentives for private developers. Land value capture allows the local government to tap into this increasing land value, in locations made attractive and livable through government investment. The concept is a way for the city to ensure that some of the value generated by public sector investments and interventions — which the private sector can benefit from, and build on — is reinvested into the community.

When managed well, the benefits of land value capture can promote inclusive and equitable urban development, creating a virtuous cycle by paying for more services like basic sanitation and public transit, and amenities like parks and green space. Land value capture ensures that government action generates broader public benefits.

How Can Governments Apply Land Value Capture?

One common tool used by cities to apply land value capture is through property taxes, which can provide stable revenue for local governments. When property values increase, the government can capture some of that additional land value and direct it to public infrastructure and services that benefit the community. In developing cities, however, the challenge often lies in establishing a clear record of who owns what land.

Governments can also utilize other land value capture tools, such as:

- Charges for building rights: Developers pay the city a fee to expand their building’s footprint beyond what is normally allowed.

- Betterment contributions: Developers contribute money to improve public services and infrastructure that directly benefit residents or tenants of their property site.

- Land readjustment schemes: Landowners collectively pool their land and contribute a portion of their property to the government, which then redesigns the area with better infrastructure, public services, parks, etc. In return, landowners receive an increase in property value from the neighborhood improvements.

Along with generating public revenue, land value capture can mitigate some harmful effects of gentrification. Often as a city develops and land prices increase, lower-income residents and small or informal businesses face displacement because the cost of living and doing business becomes unaffordable.

Using land value capture, governments can redistribute some of the revenue generated by higher-end developments like expensive apartment buildings and luxury malls to pay for affordable housing and social services that support lower-income residents in the area.

What Are the Challenges of Using Land Value Capture in Developing Cities?

Many governance and institutional challenges exist for cities in developing countries to implement land value capture. Some of these include out-of-date or insufficient land registries that make it difficult to track and tax property ownership; lack of political will to invest in land value capture; weak institutional capacity to oversee land value capture projects; and the predominance of informal settlements like slums — where residents generally don’t have official property rights.

More developed cities have been using land value capture tools for decades, but their effectiveness in utilizing the revenue for public good has not been widely studied. In developing cities, land value capture has not been widely implemented nor studied.

What Are Some Examples of Cities Using Land Value Capture?

Still, some developing cities are experimenting with land value capture and offer lessons to others looking to get started. WRI’s new working paper looks at three examples of these early adopters — São Paulo, Addis Ababa and Hyderabad — to understand what has and hasn’t worked in terms of achieving both economic and equity outcomes from land value capture projects.

These cities represent varying income levels, urbanization patterns and governance structures in developing countries, and their experiences so far can inform a diverse range of other cities. The paper also examines how these cities overcame barriers to effectively implementing land value capture.

Using Building Allowances (CEPACs) for Urban Improvements in São Paulo

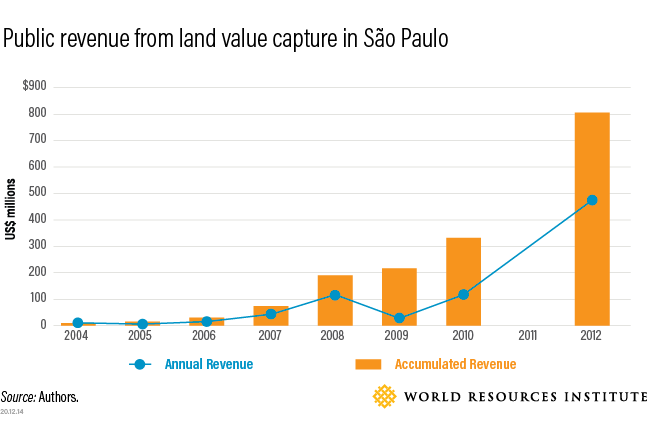

In the early 2000s, São Paulo, Brazil used Certificates of Additional Construction Potential (CEPACs) to generate revenue for infrastructure projects like public housing. Instead of applying for the right to build in a specific area, developers could purchase CEPACs on the stock market, generating revenue for the government.

The Água Espraiada Urban Operation project, in an area dominated by a favela (or informal settlement) and situated next to a stream, was one place meant to receive improved housing and drainage funded by the sale of CEPACs. This focus on improving infrastructure in a low-income area could serve as a model for equitable land value capture design.

São Paulo achieved its economic goal of raising revenue. The Água Espraiada project raised BRL 2.9 billion ($806 million) from CEPACs between 2004 and 2012. Strong political will was a key success factor.

The way the city spent the revenue, however, could have been more equitable. Only 33% of the BRL 2.9 billion has gone to services that directly benefit local low-income families. 59% has been channeled to road infrastructure that benefits higher-income car owners. And many low-income families displaced during construction did not receive adequate alternative housing.

Additionally, the city did not set aside enough land for public infrastructure and services, and had to buy back land at a higher price after the project was finished. Considering this kind of risk from the beginning is important to avoid unnecessary costs, as is ensuring that revenue raised from land value capture prioritizes services for low-income residents for broader public benefits.

Redeveloping Addis Ababa’s Central Lideta Neighborhood

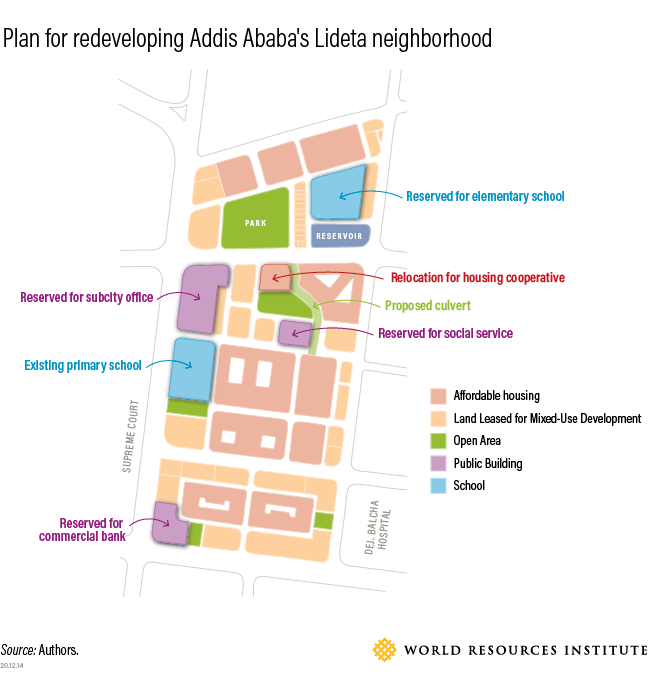

The Ethiopian government controls land titles in the country, allowing cities like Addis Ababa to lease land to individuals and businesses, which brings in public revenue to fund infrastructure projects. In 2005, Addis Ababa started a redevelopment project in the small, central neighborhood of Lideta to bring in new stores, affordable housing and green space.

The initial design of the Lideta project prioritized equity and sustainability. Meetings to discuss redevelopment plans were open to the public. The site design included mixed-use buildings, affordable housing, public infrastructure and green space meant to improve the neighborhood’s livability.

The project fell short of generating fiscal and equity benefits, however. Ineffective payment collection for leases and unclear property records made generating revenue difficult. Additionally, the construction that has been completed in Lideta caters to higher-income residents, and many original residents have been displaced.

Several lessons can be drawn from the Lideta project. More formal, transparent property records can help the city collect and track revenue, and ensure fair land valuation. Building local capacity and trust is especially important in Addis Ababa, where land value capture is relatively new and trust in government is low. Finally, making provisions for returning revenue raised from land leasing and property taxes to longtime residents of areas being redeveloped can ensure that vulnerable communities benefit.

Land Value Capture Along the Outer Ring Road in Hyderabad

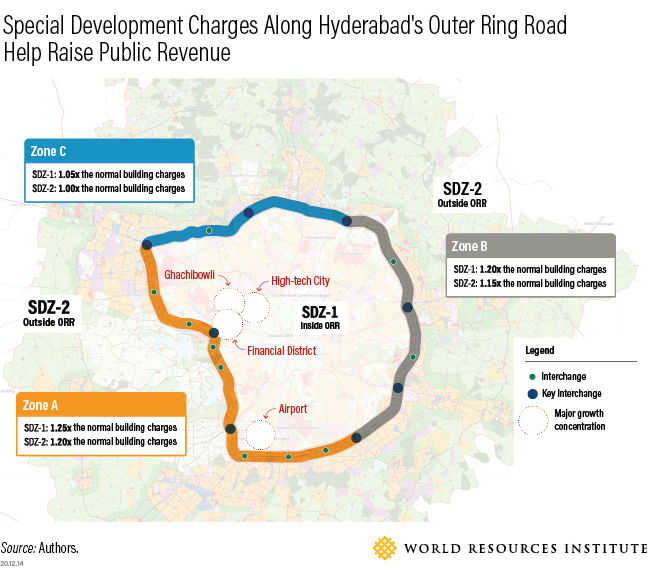

Hyderabad, India, is using three land value capture mechanisms to raise revenue for development around the Outer Ring Road, a road that circles the city and allows cars to bypass the crowded city center. First, the city uses a mechanism called “special development charges” to charge up to 1.5 times the normal fee for building permissions, tapping into growing demand from developers for space along the transit corridor.

Second, “development deferment charges,” managed by villages along the Outer Ring Road, are fees levied on landowners who keep lots vacant. These charges are meant to discourage landowners from holding on to land for financial speculation.

Lastly, area development plans (yet to be implemented) would include things like land readjustment schemes that pool and redesign multiple parcels of land in an area — generating value for landowners and revenue for the government.

Both special development charges and development deferment charges have generated some revenue for Hyderabad. But accurate and transparent data is hard to come by, making it difficult to track how effective these land value capture mechanisms have been.

Area development plans are best positioned to increase the value of land in a planned way and generate more revenue for the city over the long term, but they require more coordination and political will.

With all land value capture mechanisms, integrating land development planning with transportation planning and financing is key. But this isn’t happening.

So far, development along the Outer Ring Road transit corridor has concentrated around wealthier areas, and many poorer areas are still without basic infrastructure and services liked piped water and sewage. With improved data collection and area development plans, Hyderabad stands to gain more revenue from land value capture — and to help communities along the Outer Ring Road grow more equitably.

How Cities Can Use Land Value Capture

Our three case studies showed that, although challenges remain, developing cities can benefit from generating significant public revenue if they implement land value capture successfully. Understanding the local political, financial and governance context is critical to that success — both in capturing land value and in using the resulting revenue equitably, to ensure more vulnerable communities in cities aren’t left behind by development.

To learn more about how cities in developing countries can lay the foundation for successful land value capture, download our working paper, Urban Land Value Capture in São Paulo, Addis Ababa, and Hyderabad: Differing Interpretations, Equity Impacts, and Enabling Conditions.

This blog was originally published on WRI’s Insights.

Maria Hart is a Research and Engagement Specialist at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.