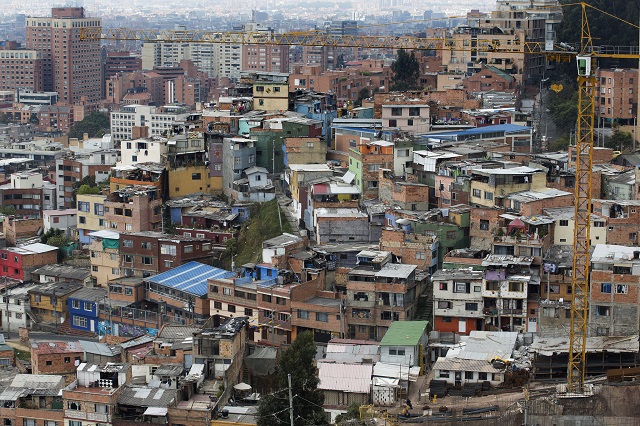

This crisis has made it imperative to accelerate change in our cities, especially for Latin America’s most vulnerable urban residents. Photo by Dominic Chavez/World Bank

The large cities in the Latin American region all have one thing in common: the opportunities for employment and income are concentrated in a few districts while, more and more, sprawling housing zones are located on the outskirts of cities and metropolitan areas. Commuter neighborhoods and cities house the vast majority of the low-income population, which has limited access to basic sanitation, water and sewers. This is because real estate development has been guided solely by the economic rationale of maximized profits, seeking out the cheapest parcels of land to build housing for low-income people.

As a result of this exclusive and inefficient urban development policy, Latin American cities have abysmal levels of accessibility. For example, a study published by World Resources Institute shows up to half of Mexico City’s residents have restricted access to jobs and services due to their home location and transport options. Against this backdrop, the COVID-19 crisis creates a vicious circle: the poor distribution of access to suitable social infrastructure, clean water and sewers, for example, worsens the already grim picture of affected people and deaths, and prolongs the health crisis and its socioeconomic consequences.

Moreover, the economic crisis arising from the pandemic may aggravate and further increase the barriers built in our cities. There is, for example, the risk of a collapse in public transport, which was already financially troubled before the crisis due to the loss of revenue caused by the fall in demand. Measures to prevent its collapse are urgently needed to avoid even more significant deterioration in accessibility. But we cannot limit ourselves to merely seeking to maintain current levels of accessibility, especially for low-income inhabitants.

The crisis has made it imperative to accelerate change in our cities. Otherwise, Latin American cities risk becoming centers of further humanitarian, social and economic crises. Recovery planning can be an opportunity to rethink how cities can become fairer and more human. It is also necessary to be bold and strengthen partnerships — domestic and foreign — if we want a more sustainable, more equitable and more climate-friendly future. In this context, we list some priority measures here that can help cities build a new “normal”:

1. Improve existing public services through low-cost, high-impact investments.

For example, we suggest fostering active mobility by installing bicycle lanes and creating wider spaces for pedestrians and improving the quality of public transport. Tactical urbanism actions can rapidly redesign streets and avenues for pedestrians and cyclists, using very few resources. And, using only signage and paint, cities can also quickly set up new lanes reserved exclusively for buses, which will be fundamental in improving the speed, reliability and efficiency of bus routes. Cities can create zones free of pollution and emissions, giving preference to travel on foot and by bicycle.

2. Invest in social, economic and residential infrastructure in marginalized areas.

This is not a new priority. But, more than ever, it is a crucial one. These investments would help to address the abysmal inequality in our cities and avoid a repeat of the tragedy that these cities are experiencing in this pandemic — thousands have fallen ill or died because they lack the means to maintain minimum health care standards. Improved infrastructure would also make it possible to create centers of employment, entrepreneurship and income within these communities, reducing the overuse of public transport systems.

3. Think innovatively about the mobilization of resources.

Some of these actions require few resources, or simply the modification of existing subsidies. For example, to increase financing for public transportation, cities can introduce charges for trips in private motorized vehicles, or increase the charges for the use of public spaces for parking private cars. The financing capacity of Latin American cities is notoriously limited. This is due to historically low tax bases, limited economic growth, fiscal restrictions imposed at the national level and dependence on transfers from the federal level, among other factors. However, cities should also seek new, innovative sources of financing. And here is where we introduce our last recommendation.

4. Build back better by making sustainability the axis of development for your city.

Cities are central to dealing with climate change and are the ones to gain most from low-carbon, sustainable growth. After all, their inhabitants are knowingly directly affected by the contamination of air and water and will be directly affected by climate change. In addition to more apparent benefits of low-carbon growth for their inhabitants, cities may have much to gain financially from making sustainability an axis of their investment plans, for three reasons.

First, as climate risk begins to influence the administration of the portfolios of institutional investors, the potential for green financing will continue to grow exponentially. With sustainable investments in energy, construction, transport, waste management and industrial energy efficiency, cities have enormous potential to support new credits and the issues of green securities in domestic and international markets.

Second, creating a plan for a sustainable recovery facilitates the establishment of new global alliances for mobilizing resources. Multilateral institutions may be a bridge for this process, helping to capture resources. Sustainability is already a guiding principle in the mandates of the multilateral partners of development in Brazil, such as the World Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB), the Development Bank of Latin America (CAF) and the New Development Bank.

Finally, the creation of a pipeline of sustainable infrastructure projects relating to mobility, housing, energy, water, waste and the digital economy makes it possible to develop better practices from the start of these projects. Municipal governments should establish a vision for and commitment to sustainability, and define a clear strategy with targets, goals and indicators for these projects, which will help to attract private financing. In the same way, cities will need to standardize investment procedures, including reducing bureaucracy whenever possible.

This moment of suffering is even more intense for the most vulnerable people in Latin American cities. May it at least be an opportunity to (re)construct cities that are fairer and more sustainable.

This blog post originally appeared in the C40 Knowledge Hub.

Rogério Studart is Senior Fellow for The New Climate Economy at World Resources Institute.

Sergio Avelleda is Director of Urban Mobility at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.