Brisbane, Australia’s South East Busway saw both a ridership increase and time travel reduction, in comparison to previous commutes. Photo by Harshil Shah/ Flickr

The world’s great public transit systems: Tokyo’s Metro, London’s Tube, Hong Kong’s MTR…and Mexico City’s bus rapid transit corridors? Trains are often seen as the pinnacle of modern urban transport infrastructure. They’re green and efficient, supported by permanent, complex track infrastructure. Bus rapid transit systems, on the other hand, are less flashy and often associated with their slow cousins, the local buses.

But in a new study published in Transport Reviews researchers Jesper Ingvardson and Otto Nielsen from the Technical University of Denmark point to data that suggests there’s little that separates the two approaches in many contexts.

Ingvardson and Nielsen compare 86 metro, light rail transit (LRT) and bus rapid transit (BRT) corridors using several variables: travel time savings, increase in demand from riders, modal shift, and land use and urban development changes. In some cases, the much more economical BRTs matched and even outperformed rail.

Travel Time and Ridership

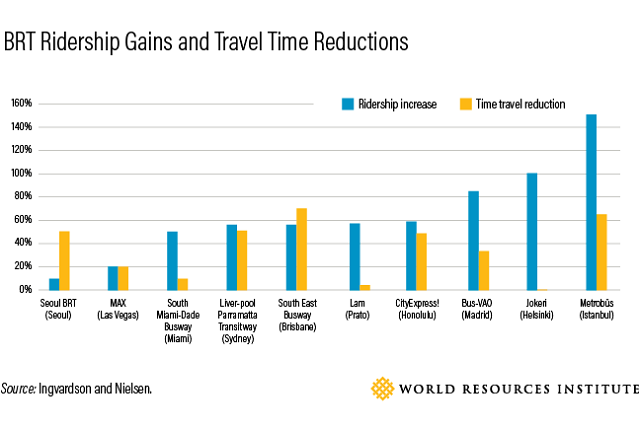

The study starts by looking just at whether BRT can reduce travel times and improve mass transit ridership on its own.

There are large variations across BRT systems regarding travel time, making it difficult to draw broad conclusions, but overall they saw declines. While Metrobüs in Istanbul produced travel time savings of 65 percent compared to previous commutes, the Bus-VAO lane in Madrid led to 33 percent savings and the South Miami-Dade Busway just 10 percent.

Ridership gains after a new BRT corridor also varied: 150 percent in Istanbul, 85 percent in Madrid and 50 percent in Miami. Ridership gains are associated with travel time savings, but also derived from other factors such as the frequency of buses, station quality, vehicle type and user information systems.

Converting Drivers to Mass Transit

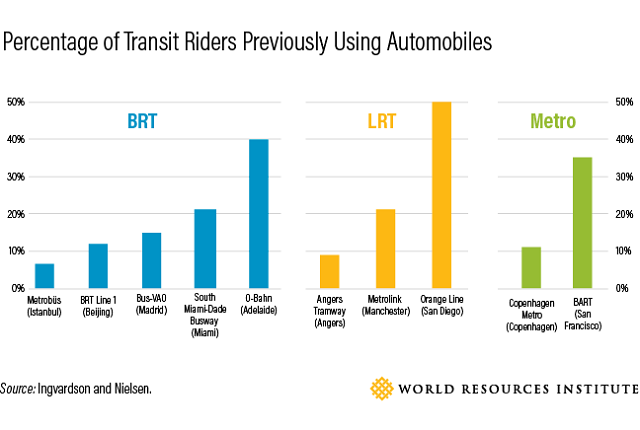

An interesting impact of mass transit implementation is its effect on drivers. In the 13 cities where Ingvardson and Nielsen studied BRTs, the number of riders who shifted from car trips ranged from 5 percent (Stockholm) to 40 percent (Adelaide), with a simple average of 17 percent. This figure is similar for the 24 LRTs (average 16 percent) and slightly lower than for the two metro systems included in the study (average 23 percent).

One caveat to these conclusions is that BRT and LRT corridors tend to be much smaller than metro corridors in terms of total volume of riders. The notable exception is Istanbul’s Metrobüs, which serves more than 600,000 passengers a day, 4 to 9 percent of which would otherwise be car users.

Land Values and Development

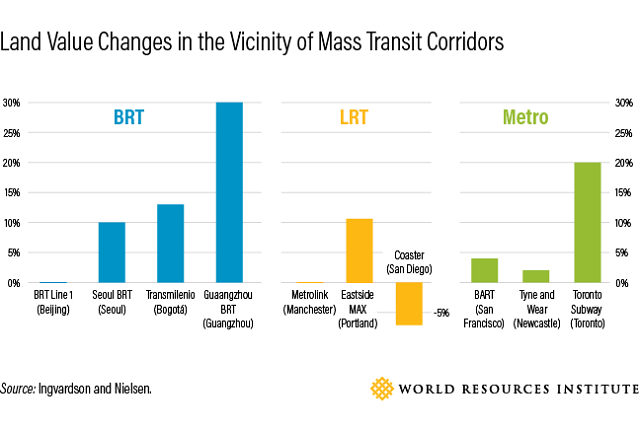

Despite the permanence of train tracks, Ingvardson and Nielsen found no significant difference in how BRTs, LRTs or metro impact land value. Land value increases ranged as high as 30 percent for BRT corridors; 32 percent for LRT; and 20 percent for regional rail and metro corridors. In several BRT and LRT cases, no increase in land value was observed; for the Coaster rail corridor in San Diego, a negative value was recorded.

Land value comparisons are difficult, however, because of varying assessment methodologies, distances to stations, and before and after time periods. It’s likely these conclusions should be taken with a grain of salt. The particular mass transit mode is less important than other factors, like access conditions, the urban environment, and service characteristics (e.g., frequency, speed, comfort and pricing). For the 41 projects with quantitative data, the differences in land values achieved by the different modes are not significant.

BRT, LRT and regional rail also show increased residential and commercial development around stations. Nevertheless, the improved access provided by transit is an insufficient driver of better land use. Other complementary activities, like changes in regulations, government support for investment in real estate, and investment in pedestrian connectivity, are required to achieve urban development goals. The most recognized case is Curitiba, Brazil, where 45 percent of the long-distance motorized trips in the BRT vicinity use the buses. There is also evidence of positive urban development impacts from the BRTs in Ottawa, Boston, Cleveland and Los Angeles.

There Is No Superior System

Ingvardson and Nielsen recognize that there are limitations in the data collected, analytical methodologies and even in the distinction between transit modes. There isn’t always a clear difference between light, regional or metro rail, for example, or between bus rapid transit and bus priority corridors.

Despite these limitations, the researchers conclude that BRTs can improve travel times, modal share and urban development at rates similar to those reported for light rail and metro. This evidence contradicts conventional wisdom. It is not possible to categorically say trains have greater benefits than BRT; they are not always superior. Context matters, not just the material of the wheels or the permanence of the tracks.

Dario Hidalgo is Director of the Integrated Transport Practice for WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.