Women in Colombia’s capital demonstrated particular mobility patterns, personal safety concerns and other needs often ignored in a transport sector still dominated by men. Photo by Galo Naranjo/Flickr

Cities around the world are slowly realizing that gender dynamics play an important role in how people interact with transport systems. Taken as groups, women and men tend to have different travel patterns, different safety concerns, and even make different decisions as drivers and operators. But these differences have been largely ignored or been invisible. Little data is disaggregated by gender and the majority of planning and decision-making positions in transport are held by men.

In a new joint publication by WRI Ross Center and Despacio, a non-profit research center based in Bogotá, we analyzed the transport needs of women in Colombia’s capital of more than 7 million and the disparities resulting from excluding this data from planning.

The report (published in Spanish) is intended to enable discussion on this important issue and to provide additional data to foster the analysis and inclusion of gender as a transport issue in Bogotá – and around the globe. It utilizes both qualitative and quantitative data through a methodology that can be replicated in other cities with access to similar data, such as mobility surveys, road safety data and perception surveys.

The data was analyzed through four different perspectives that reflect major ways women experience transport differently than men: mobility patterns, personal safety, public policy, and employment and leadership.

Mobility Patterns

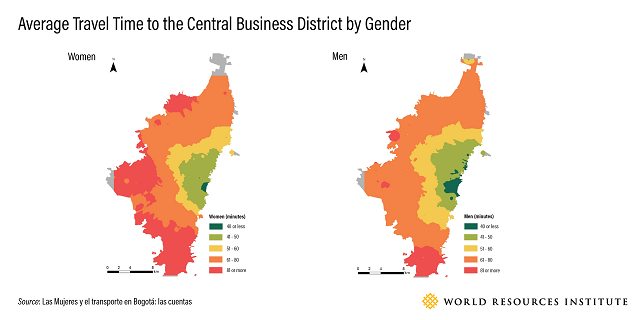

Number of daily trips: Female commuters in Bogotá spend 11% more of their time on trips to work compared to male commuters. This difference is even higher for women living in low-income neighborhoods in the periphery. They travel longer distances and spend more time on public transit even though, paradoxically, they come from areas with lower transit accessibility.

Destinations: Men make more trips for work outside the central business district, which may imply they have access to more diverse job opportunities.

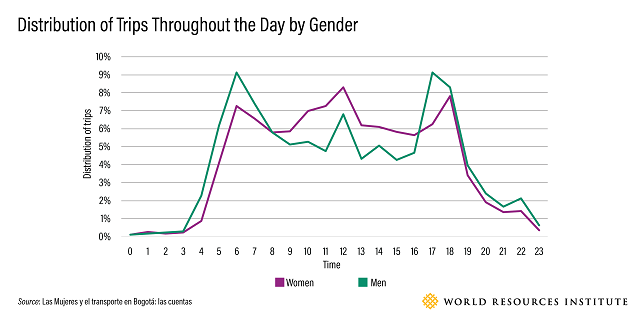

Peak hours: Women and men have different peak travel hours. One likely explanation is that the role of caregiver disproportionately falls on women. Women are more likely to make trips involving picking up and dropping off children from school, taking them to after-school activities, running errands and going to health appointments. As a result, they make more and shorter trips during the day than men. This has implications on transport data collection – which traditionally has focused on the morning and afternoon commuting hours – and subsequent public transport planning.

Road safety: Most female road crash victims are reported in low-income neighborhoods with low access to transport services and high numbers of women walking amidst poor infrastructure conditions, circumstances that make traffic crash risks higher. Thus, to improve road safety for women, the neighborhood scale may be more important than the city scale. Interventions like low-speed zones in strategic areas could reduce traffics deaths sharply.

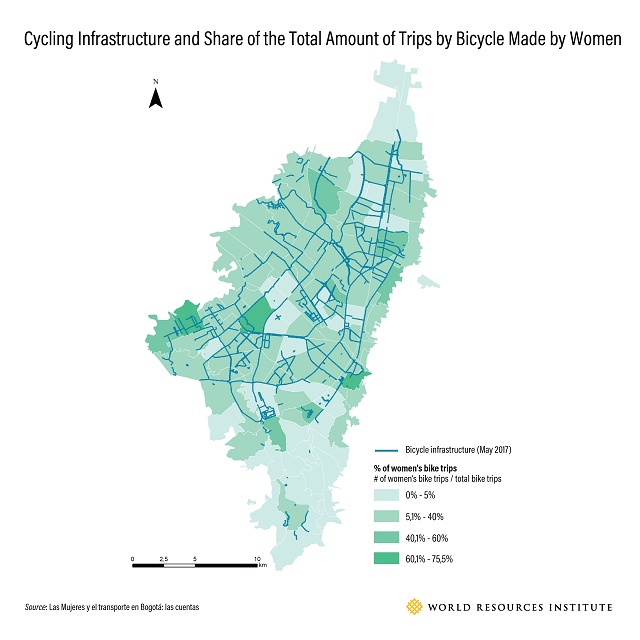

Cycling: In a city known for its love of biking, women make up only 21% of cyclists. Dedicated safety infrastructure seems to be key to cycling patterns among women. Most trips by women are made in areas where infrastructure is available. Additionally, crashes for men and women tend to occur in different places, which shows the importance of including gender in road safety analysis and countermeasures. A more comprehensive approach to cycling safety in Bogotá would take these differences into account, for instance, by including potential trips for women that account for scenarios where infrastructure is expanded in addition to current demand, which is mostly male. Such an approach could increase the number of women cyclists by providing more routes they feel safe and comfortable using.

Personal Safety

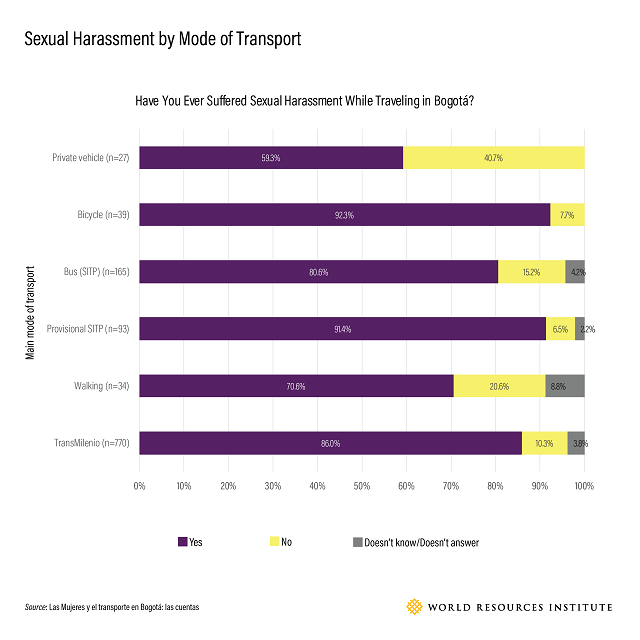

Sexual harassment: About 85% of participants in a 1,000-women online survey reported having suffered sexual harassment while traveling in the city across all transport modes. Another study published last year in the Journal of Transport & Health also found high levels of “sexual misconduct” within Bogotá’s transport system, and found it was having a lasting and significant effect on women’s travel patterns.

Still, more information on all cases – our survey did not have a big enough sample for making more detailed analysis and might be biased to social network users – and a better reporting system are key to developing effective mitigation measures. Some efforts to reduce sexual harassment in transport have seen mixed results. It is critical to gather more data in order to evaluate the impact of future and current programs, like Me Muevo Segura (“I Move Safely”), for example, which works to create a safety index for women at night.

Public Policy

Legal system: Unfortunately, what behavior constitutes sexual harassment is not well defined in Colombia. The Colombian Congress, the Supreme Court of Justice and Bogotá’s local government have issued various case decisions, regulations and campaigns to improve the mobility experience of women. But from a foundational perspective, it is crucial to clearly define sexual harassment to improve reporting pathways and enforcement. Of the 85% of women surveyed who said they experienced sexual harassment in our survey, less than 10% said they reported the incident to authorities.

Public transit: The city exercises more control over the public transit system than any other mode of travel, and programs like Mujeres viajan seguras en TransMilenio have been implemented in order to reduce sexual harassment and make women feel safer using the system. But these efforts are hard to enforce due to the system’s high demand during peak hours, the ambiguity of the definition of sexual harassment and the lack of a clear process for complaints.

Bogotá public transit users at peak travel time. Photo by Carlos Felipe Pardo

Employment and Leadership

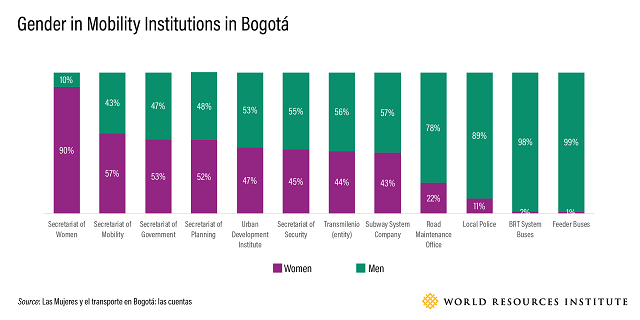

On a positive note, the face of leadership in Bogotá is changing. Women now represent more than half of the city officials in most planning and mobility agencies.

However, among law enforcement and private bus operators, the gender disparity returns. Evidence in the report shows female bus drivers are involved in fewer road crashes, suggesting that creating the conditions for more women drivers could result in improved road safety for everyone.

The implications of more gendered data for transport are far reaching. Transportation has the potential to advance poverty alleviation and promote more sustainable cities, but not if safety and accessibility are a barrier to use. As urbanization accelerates, cities are requiring more transport provision – to connect far-flung areas, to improve access to key services like jobs and education, and to improve productivity.

This report is a step toward understanding the different travel experiences of women; to identifying barriers and opportunities for increasing women’s use of the transportation system to access education, employment and services; to improving their lives and livelihoods; and to enabling them to contribute meaningfully to the economic, social, political and environmental well-being of the city.

The methodologies used can be replicated to help cities pinpoint key actions, especially in low- and middle-income cities with similar contexts to Bogotá. Encouraging more women’s voices in transport leadership and gathering more gender-disaggregated data will help ensure transport systems are safe and productive for everyone.

Download ‘Las Mujeres y el transporte en Bogotá: las cuentas’ from wrirosscities.org.

José Segundo López is a Research Analyst for Mobility and Road Safety at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.

Natalia Lleras is a Project Manager for Mobility and Road Safety at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.

Claudia Adriazola-Steil is Deputy Director of Urban Mobility and Director of Health and Road Safety at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.