A New Yorker may not think about the forested Catskills Mountain Range upstate as she pours a glass of water. Londoners probably don’t consider the Amazon rainforest as they watch the rain falling on city parks. And folks in Addis Ababa are probably not thinking about the Congo Basin as they eat injera, an Ethiopian staple made from the grain teff.

And yet, forests near and far affect these urbanites’ daily lives far more than most people realize.

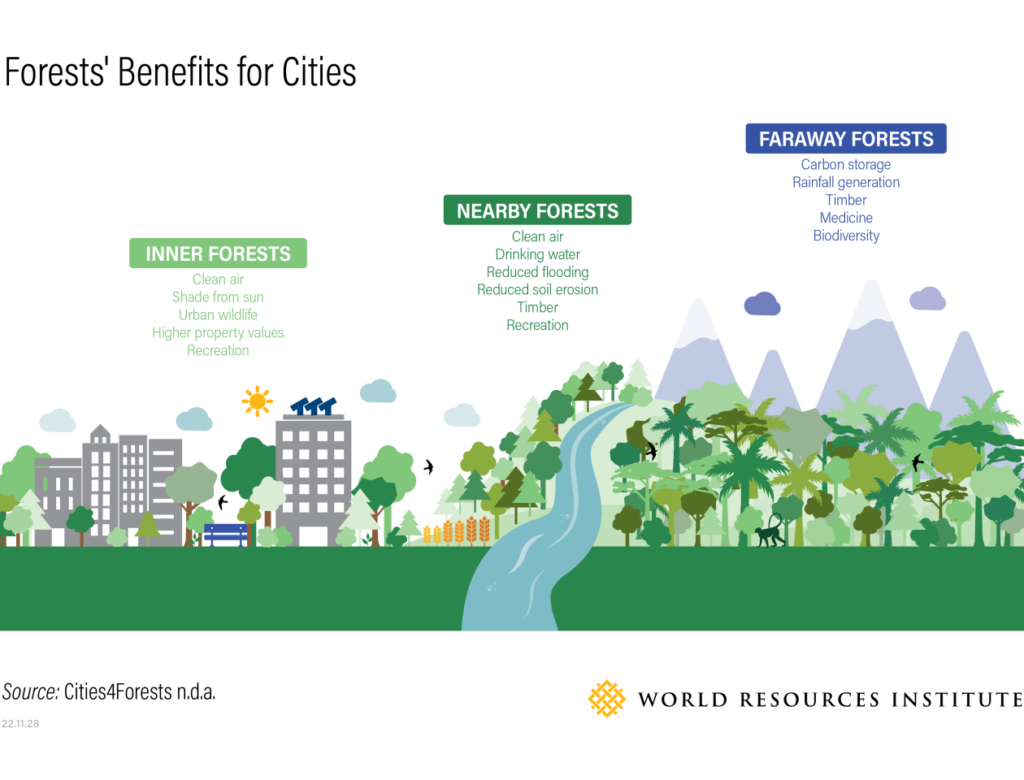

While city residents increasingly recognize the benefits of urban trees to reduce stress, sequester carbon, and clean and cool the air, the benefits of forests outside cities receive far less attention. A growing body of research shows that even forests located far away from urban centers provide tremendous benefits in regulating the global climate, water and biodiversity systems that are essential to people’s health and quality of life.

New research led by WRI and Pilot Projects through the Cities4Forests initiative synthesizes the benefits that forests at three scales — inner, nearby and faraway — offer cities. This report provides the scientific imperative for city-led policies, incentives and investments that help conserve, restore and sustainably manage forests at each of these scales.

Here, we outline the many benefits across four categories that forests provide to cities.

How Forests Improve People’s Health and Well-being

Forests and trees make cities better places to live. They help people breathe, think, exercise and relax; reduce extreme heat; create more walkable streets; and more. These benefits require careful spatial and ecological planning — trees must be in the appropriate place and receive care and maintenance over time.

A few of forests’ health benefits for city dwellers include:

Trees and forests can change the microclimate and improve air quality.

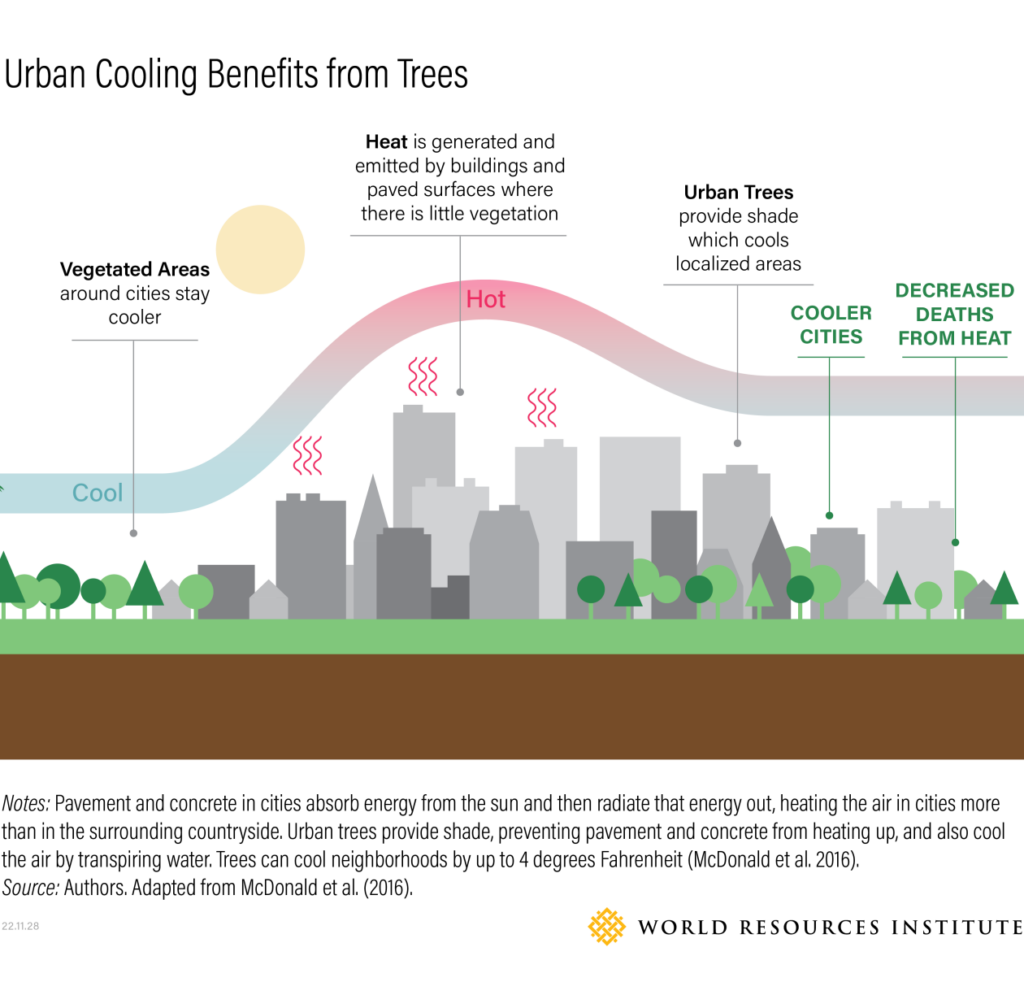

City temperatures often soar thanks to the urban heat island effect, where the built environment leads to higher temperatures in cities than in surrounding areas. This, in turn, can increase smog and ozone, cause spikes in water and energy demands, and increase the risk of heat-related illnesses and deaths.

Urban trees and forests provide shade and cool the air through evapotranspiration, through which trees pull water from the soil and release it through their leaves into the air. This reduces the risk of heat-related illness and makes cities more comfortable. Natural forest areas are especially effective, as are trees with wide, dense canopies.

It’s important that trees are well-dispersed throughout the city so all neighborhoods experience their benefits.

For example, in Toronto, as part of an effort to consider forests as essential infrastructure in the city, urban planners mapped the greater metropolitan region’s forest canopy cover and measured other metrics, including surface temperatures. The results were striking: In areas where forest canopy cover was high (often greater than 70%), surface temperatures were below average. In built areas with low canopy cover, surface temperatures tended to be above average.

Additionally, cities have notoriously poor air quality. This causes millions of excess deaths each year globally, especially in lower-income countries.

Carefully planned and managed urban forests can improve air quality by removing and dispersing air pollutants. This benefit is often touted, but even the most extensive and well-managed urban forests still only remove a fraction (often less than 1%) of a city’s pollution. A tree-based strategy should be carefully planned to maximize benefits and be combined with plans to reduce pollutants at their source.

Trees and forests improve mental and physical health.

Traffic, heat, pollution, excessive noise: Living in cities can be stressful. Trees and forests can provide tranquil spaces to exercise, gather and relax while reducing noise and pollution.

Spending time in nature is especially important for children’s developmental health. Research shows that kids who regularly play in natural areas tend to have better spatial awareness and coordination than those who don’t. Access to nature also helps people concentrate, which can improve focus in children and adults with ADHD.

Outside cities, keeping tropical forests standing can reduce the spillover of infectious diseases, including novel viruses, from animal hosts to humans.

Forests, especially biodiverse ones, provide the blueprints for new medicines.

Many people around the world — up to 95% of the population in developing countries — rely on natural remedies for primary care. Wild forest plants have provided compounds and genetic material for making antibiotics, anticancer agents, anti-inflammatory compounds and analgesics used around the world.

Forests support the pollinators that help produce urban food supplies.

About 35% of food produced globally comes from 800 plants that rely on pollination by insects and other animals. Forests provide critical habitat for many of these pollinators. In doing so, they indirectly contribute to improving food access and security.

Protecting biodiverse forests can reduce risks of zoonotic and vector-borne diseases.

Deforestation, forest degradation and associated wildlife trade has been linked with the spread of diseases that jump from animals to humans, including Ebola virus, yellow fever, malaria, Zika virus and corona viruses such as COVID-19. Conserving tropical forests and sustaining their high levels of biodiversity can decrease transmission of some infectious diseases to humans.

Forests and trees help build communities.

Forests can bring people in cities together. They often serve as gathering places and sometimes have spiritual significance. Restoring forests can foster collaboration and create a sense of place.

But forests are often unequally distributed, with lower-income areas tending to have fewer trees and access to natural areas. Engaging communities to plan and integrate trees and forests into neighborhoods with marginalized and low-income residents can help address systemic inequalities.

How Forests Support Cities’ Water Systems and Reduce Risks

Many cities struggle to provide clean water, address flooding and erosion, weather droughts and deal with increasingly erratic precipitation patterns. Forests and trees at all three scales can help with these water challenges.

Forests can help provide clean water.

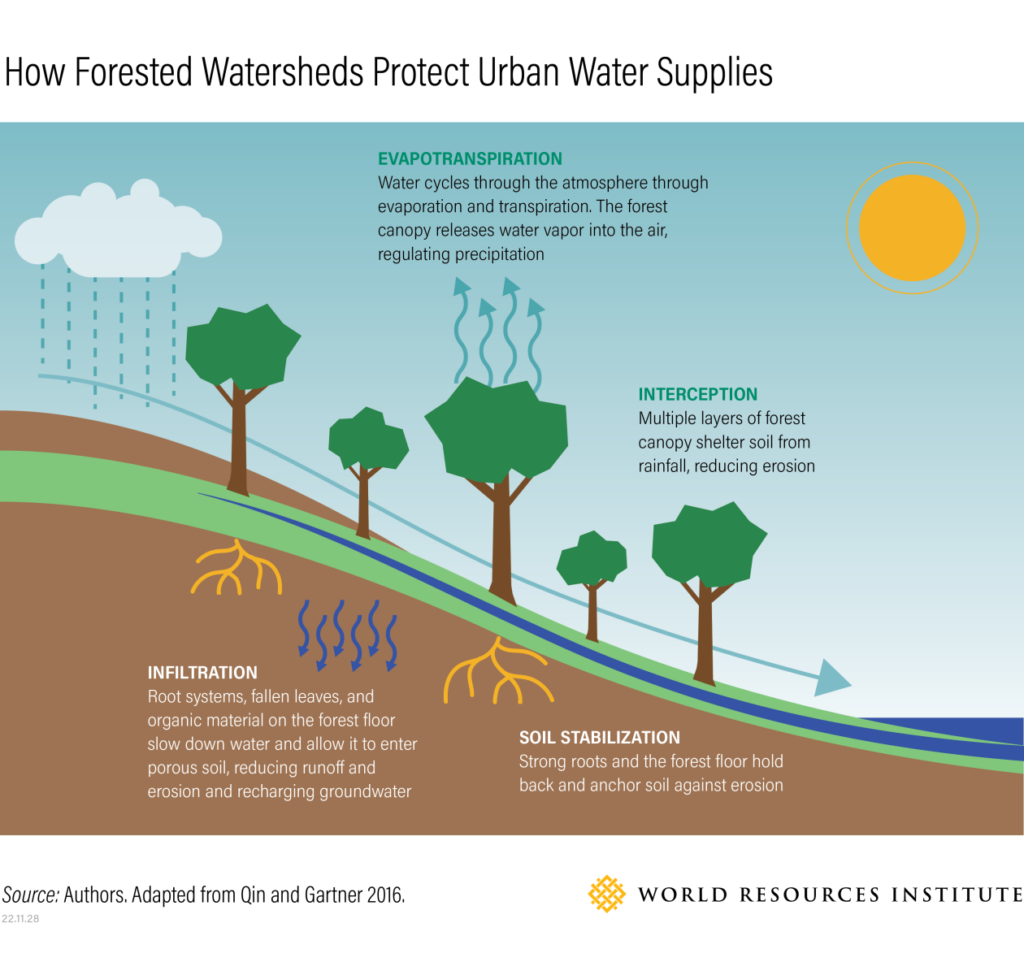

In many cities, contaminated drinking water causes severe health issues like diarrhea and dysentery. Reliable water treatment, however, can be costly. Forests in nearby watersheds can protect water supplies from pollutants, prevent soil erosion and filter sediment, keeping surface waters and aquifers cleaner and reducing treatment costs to cities. Mature, native forests provide these benefits more reliably than plantations, so preventing deforestation in watersheds is critical.

Forests help prevent floods.

By 2030, riverine flooding will affect around 130 million people and result in $535 billion of damages to urban property annually. Nearby forested watersheds regulate water flows and help mitigate flooding and landslides.

Forests intercept and store rainwater, reducing stormwater runoff. Their roots act like a sponge, holding water in the soil when there is too much, and slowly releasing it during drier periods. And within the city, trees and other vegetation in bioretention areas, green roofs and bioswales can complement engineered infrastructure like storm drains to manage urban stormwater.

Trees and forests can improve water supply.

Water scarcity caused by drought, groundwater depletion or reduced river flows affects many cities around the world — especially in arid regions. Preventing deforestation and restoring forests can increase soil infiltration and groundwater recharge. (Reforestation can also initially reduce water supply because newly planted trees grow fast and use water; the overall balance depends on the climate, tree species and forest structure.)

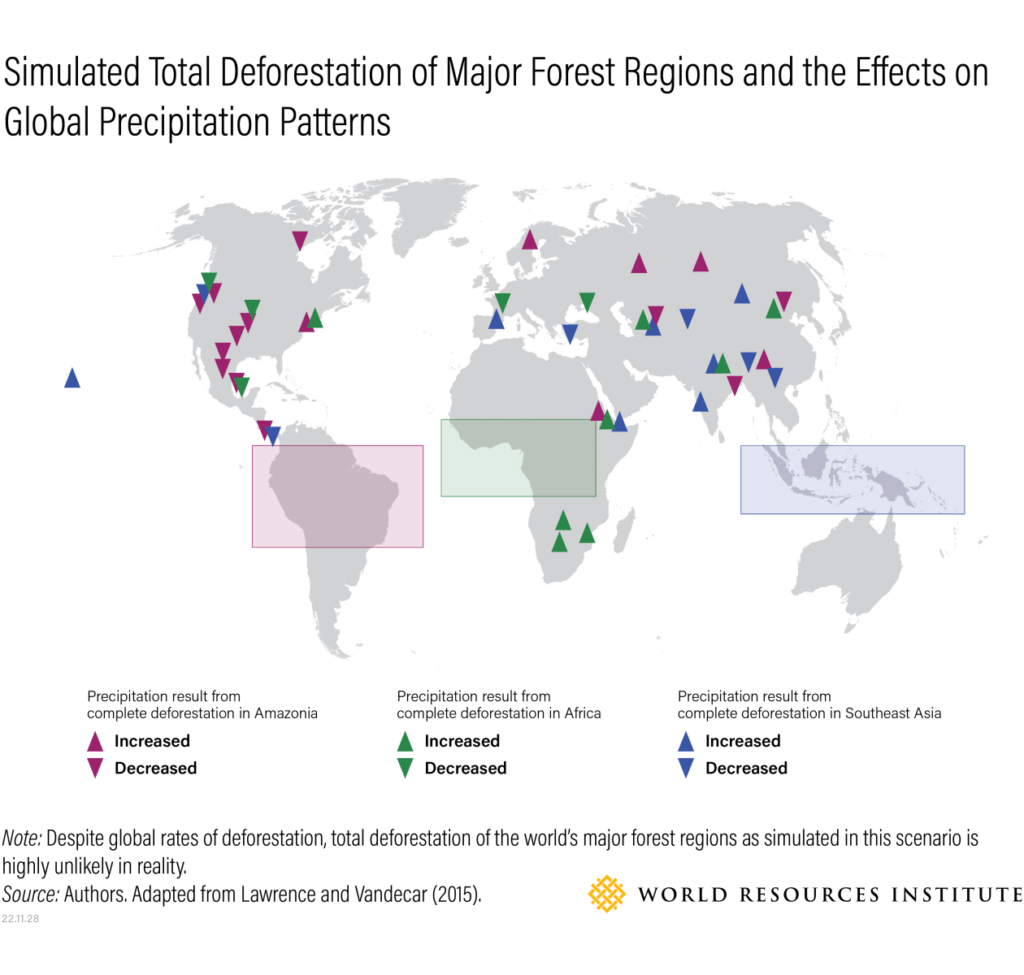

Forests also modulate rainfall patterns at regional and even global levels. Forest evapotranspiration acts like a giant pump, sending water into the atmosphere and redistributing it before it falls as rain.

Forests help provide stable and consistent water supplies.

Urban residents are vulnerable to increasingly erratic weather patterns fueled by climate change, including longer and more intense droughts and heavy rainfall. Forests can help reduce this variability.

Forests, especially large tracts of intact forests and rainforests, recharge atmospheric water supplies and influence rainfall patterns hundreds to thousands of miles away. These “flying rivers” maintain water flows to some of the world’s largest cities (and most important agricultural regions), and are particularly linked to large tropical forests like the Amazon, the Congo Basin and the forests of southeast Asia. Removal of these forests threatens to disrupt global rainfall patterns — increasing rain in some places and decreasing it in others — with potentially disastrous consequences. Conserving these forests is absolutely critical to sustain global precipitation patterns.

For example, Colombia’s alpine tundra (páramos) and cloud forests provide water to about 70% of the country’s population. They also impact the generation of hydropower, which provides 73% of the country’s electricity needs. Deforestation and climate change, however, threaten to upset the country’s water and electricity supply: Between 2002 and 2019, Colombia lost more than 4.3 million hectares of forest cover, while warming temperatures are projected to further increase the volatility of precipitation patterns.

How Forests Help Curb Climate Change

Heat waves, flooding, rising sea levels and droughts threaten both the well-being of urban residents and the costs of operating a city. At the same time, cities are some of the biggest drivers of the climate change crisis. For example, cities use 70% of the world’s energy, but comprise less than 60% of its population.

Forests can help cities both mitigate and adapt to climate change. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions from sources like transportation, infrastructure and city consumption are important first steps, but forests can help cities go further in tackling the climate crisis.

Forests cool the air and reduce energy demands.

Within cities, the cooling effect of trees and forests is a double win: Trees can help residents and businesses adapt to rising temperatures, while simultaneously reducing emissions by decreasing the demand for air conditioning powered by fossil fuels. They can also reduce heating needs by providing shelter from wind. In the United States alone, urban forests reduce electricity use by 38.8 million MWh annually, saving consumers $4.7 billion and avoiding emissions valued at $3.9 billion annually.

Forests sequester carbon.

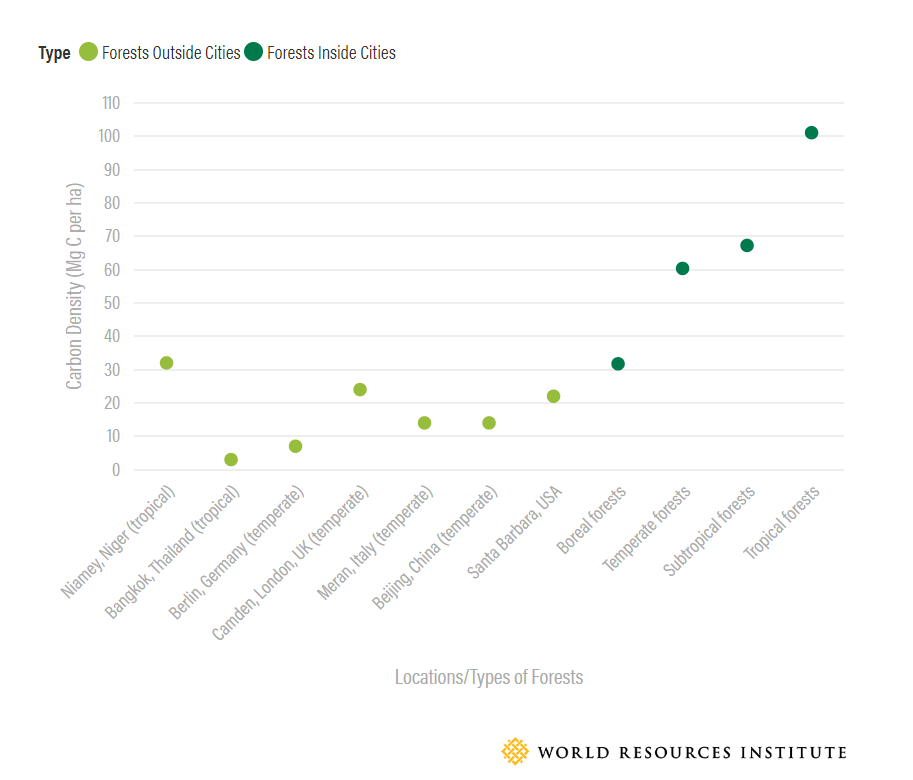

Urban trees also sequester carbon in wood and soil, but the potential here is quite small, often less than 1% of overall city emissions. Throughout China, for example, the carbon sequestered by urban vegetation in its 35 largest cities could offset only 0.33% of these cities’ annual emissions. Limited and expensive land, lower sequestration rates than nearby or faraway forests, and maintenance that relies on fossil fuels mean that urban trees are sometimes carbon neutral or even carbon positive, emitting as much or more carbon as they sequester.

However, conserving and restoring forests outside cities by changing consumption habits can go a long way towards reducing emissions. Forests outside cities, especially tropical forests, are large reservoirs of carbon that are released if the forest is cleared or degraded. If forests are conserved, those stores are protected and forests continue to suck up more carbon over time, providing increased mitigation against climate change.

Cities can play a big role in realizing this carbon opportunity and can help meet their own emissions-reduction commitments in the process. For instance, cities can lower their forest-carbon footprint by ensuring that the commodities they purchase for city infrastructure and operations — such as timber, paper and food — come from deforestation-free supply chains.

For example, Cities4Forests’ winning proposal for the Van Allen Reimagining Brooklyn Bridge design competition envisions rebuilding New York City’s Brooklyn Bridge using Forest Stewardship Council-certified timber. Specifically, the design proposes that 11,000 new planks for the Brooklyn Bridge be sourced through a sustainable timber partnership with the Guatemalan community of Uaxactún, which protects more than 80,000 hectares of rainforest. The community’s low-intensity harvest model — one tree per 0.4 hectares every 40 years — has provided income to the community while keeping the rate of deforestation at nearly zero for more than 25 years. While still just a design concept, executing the plan would help address the root causes of deforestation and position New York as a city leader in protecting forests.

How Forests Support Biodiversity that Benefits Cities

Biodiversity — plants, animals, fungi and bacteria — enhances all forest benefits because it makes forest ecosystems more resilient. Biodiverse forests near and far provide a suite of essential services that are important for city residents:

Biodiverse forests often provide more — and more reliable — goods and services.

Forests must be able to persist and recover from changes in the environment, including storms, droughts and a changing climate. High levels of biodiversity can serve as biological “insurance.” When an ecosystem has many species fulfilling similar roles, it can continue to function even if some of those organisms are lost or if a disease (such as Dutch elm or chestnut blight) wipes out an entire species.

Biodiverse forests store more carbon, more reliably.

Undisturbed native forests sequester more carbon and store it for longer than degraded forests or monoculture plantations. Biodiverse forests have higher resilience to fluctuations in climate, pest outbreaks and diseases than tree monocultures, making them a more reliable carbon sink. Native, biodiverse forests in watersheds are also more effective than planted monocultures at supplying water resources to downstream cities because of their structure, impact on soils and greater resilience.

Biodiverse forests can provide more reliable and richer health benefits to urban residents.

Not all green spaces in cities are equal, and natural areas — often higher in native biodiversity — provide more stress reduction and healing benefits than heavily manicured ones. Managing urban forests for biodiversity can provide access to nature within cities and create more resilient urban forests, essential for delivering other forest benefits.

Tropical forests hold most — up to 90% — of the planet’s terrestrial biodiversity. And while inner forests can house high biodiversity, they also tend to have more invasive species and fewer endemics (species with very limited ranges) than rural forests. Conserving tropical forests outside cities is vital for global biodiversity conservation.

How Can Cities Protect Forests Near and Far?

Unlike traditional infrastructure, forests provide multiple services at once, and they accrue more value over time as trees mature and ecosystem services multiply. To make the most of the many benefits that forests can offer and given the alarming rates at which forests continue to be destroyed, the time to act is now. The world lost more than 25 million hectares of tree cover — an area larger than the United Kingdom — in 2021 alone. People living in cities account for the lion’s share of the world’s consumption of commodities linked to deforestation.

However, as centers of cultural and financial power and influence, cities can reduce their impact on forests, find ways to invest in them, and influence the ways people think about their dependence.

The forests most directly within cities’ control are those within their own boundaries. Cities can map and inventory their urban forests, use the data to develop robust urban forest management plans, and explore more innovative projects such as urban wood waste reuse programs. All along the way, cities should try to promote interagency and cross-jurisdictional collaboration, as well as explore diverse, long-term term financing mechanisms to maintain and expand their urban forests.

While urban forests are those most within cities’ control, engaging with all three levels of forest is key to the sustainable future of cities. Some of the biggest gains for cities can be had by conserving forests outside their boundaries.

For nearby forests, cities must work with their regional and national governments and private landholders to better manage forests. By mapping watershed forest distribution and identifying where forests are being lost, cities can prioritize conservation and restoration initiatives. For example, in their watersheds, cities could prioritize the removal of alien tree species that threaten water supplies and biodiversity, or they could prioritize restoration of degraded lands to reduce runoff and improve downstream water quality. To access finance for these projects, cities can clarify that forest protection and management are eligible infrastructure expenses that must be treated as such.

And for faraway forests, cities must better understand how the consumption of forest-risk commodities like beef, soy, palm oil and cocoa impact their forest “footprint.” By establishing a Partner Forest program between a city and a specific forest, cities can start to procure commodities from forests that are grown and harvested in sustainable ways. Establishing relationships with organizations with expertise in tropical forest conservation and raising awareness through public communication campaigns can also lead to more sustainable consumption.

The new report lists a suite of recommendations for policy and action at all three forest scales. City leaders can use it as inspiration for their own forest conservation, restoration and sustainable management projects.

This article originally appeared on WRI.org.

Sarah Wilson is the Director of Nature-Based Projects with Pilot Projects.

John-Rob Pool is the Manager of Knowledge and Partnerships for UrbanShift in the WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.

Mack Phillips is an Operations and Project Lead with Pilot Projects.

Sadof Alexander is the Communications Specialist for Cities4Forests.