Children fear Gurugram’s busy streets. Photo by Priyanka Sulkhlan/WRI India

India accounts for almost 12% of the 1.35 million road fatalities worldwide. But this public health crisis does not affect everyone equally. Children and young people are at heightened risk. In fact, road crashes are the most common cause of death for children and young adults aged 5-29 years in India. Every day, 43 children under the age of 18 die from road crashes.

The physical and mental toll of road accidents can affect children differently too. One WHO report found that children who face or even witness road crashes go through travel anxiety and many other post-traumatic consequences. Many experience short-term disabilities that can keep them out of school during crucial learning and development years. India loses an estimated 438 billion rupees every year from road traffic crashes involving children.

As part of efforts to address this specific road safety challenge, WRI India recently conducted outreach at secondary schools in the city of Gurugram to gain a deeper understanding of children’s perspectives and requirements for safety on the roads. Gurugram, located just southwest of Delhi, had the dubious distinction of leading the state of Haryana with 446 road fatalities in 2018.

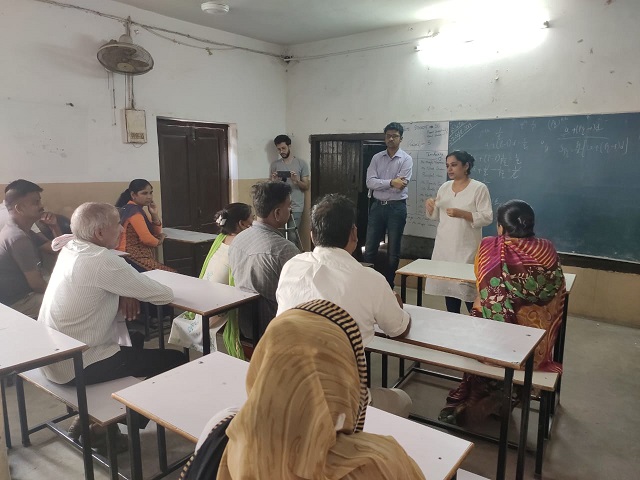

One of the key features of the initiative was a focus group discussion format in which we engaged directly with children, teachers and parents.

WRI India team members interact with students at Marumal Senior Secondary School. Photo by Aashima Bhandari/WRI India

The Focus Group Approach

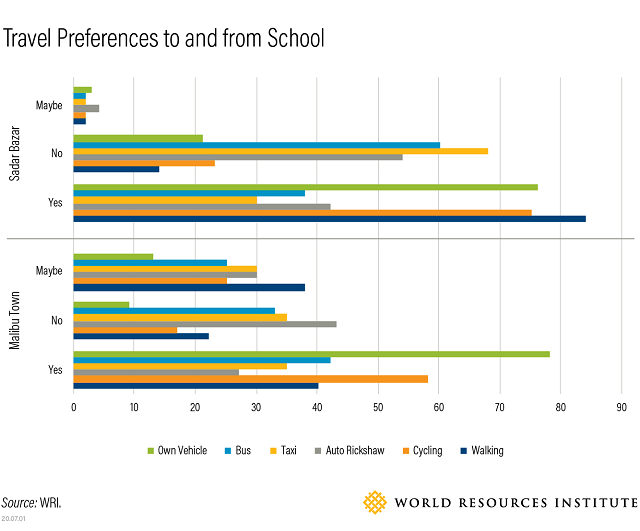

We identified five schools in two areas of the city, based on land use, category of school, income group and mode preferences. In initial conversations with schools, we observed that the choice mode of travel was dependent on affordability and varied among the schools. We deliberately included a private school from the planned neighborhood of Malibu Town in addition to schools in the heavily congested commercial center Sadar Bazar in order to highlight the different challenges faced by children across the hierarchy of streets and various built environments.

We used focus group discussions in these schools to listen to students’ personal experiences, awareness, perceptions and ideas around road safety, and to ensure that they were full participants in the effort to design safe streets that work for them. Focus groups followed a broad guide but were flexible enough to allow discussion of other issues as they arose. Each 60-minute discussion began with casual conversation to set a comfortable environment before progressing to a set of questions.

In total, 135 students from the ages of 11 to 18 participated in the study. Students were selected in collabaration with the schools to incorporate a range of age groups, neighborhood backgrounds, gender and travel modes. Depending on the students’ neighborhoods and the availability of different mobility infrastructure, modes of travel varied widely and included walking, cycling, school buses, cycle rickshaws, shared vehicles and private vehicles.

Students responding to the questions at Vedik High School. Photo by Aashima Bhandari/WRI India

Daily Barriers, Contested Space

Students who walked or cycled to school highlighted daily hurdles contending with drivers using the wrong side of the road or driving at high speeds. Other students shared personal experiences of losing a family member to a road crash or injury themselves. One girl noted she lost two years of learning due to injuries from an incident. Another group of girls expressed concern about harassement while walking on the roads, which discouraged them from walking or cycling.

Students share road safety messages after an engaging session at Government Girls’ Senior Secondary School. Photo by WRI India

Despite road safety trainings in school, the majority of the students were not aware of fundamental ideas like how to interact with traffic lights and pedestrian crossings. These awareness levels remained essentially the same across private and public schools. Interestingly, as road users, they were still able to accurately identify the top risk factors: speeding vehicles, on-street parking, crowding or congestion on streets. One specific issue of security from non social elements was highlighted with reference to gender.

Students and WRI staff at Mount Olympus School. Photo by Vibhav Kharagpuria/WRI India

One of the most revealing outcomes of these conversations was understanding how the students perceived the roads in their city. They saw roads as the congested realm of machines, a space that required continuous struggle in order to claim a place in it while undertaking their daily commutes. Most students said they grew up fearing crashes, leading many to prefer private vehicles over walking or cycling.

One student mentioned the difficulty in judging the speed of oncoming traffic while cycling. Another said she commutes with her peers on shared auto rickshaws that park at a distance across a busy intersection from their school, making the final step of reaching school a traumatizing one.

Nearly half the students said they were willing to walk to school, but only 5% actually did. Even more students – 58% – were willing to bike to school, but just 10% actually did. Students perceived both as dangerous, but cycling more so.

While studying the mobility pattern of students, we included a buffer zone of 500 meters around the schools. As per a study done by Haryana Vision Zero Project team in collaboration with Traffic Police, the school in Malibu Town had two crashes within the marked study area while in Sadar Bazar four school zones added up to 17 crashes over the last three years. This disparity between neighborhoods was reinforced during discussions.

Safety concerns were expressed more strongly by students from the public schools in Sadar Bazar, where the surrounding streets generally have less infrastructure, more congestion and students lack access to private vehicles. Though speed is a major risk factor around Malibu Town due to wider roads, the children there felt safer and more of them were able to travel in private vehicles.

Preferences are generally higher for walking and cycling than the number of children actually walking and cycling. Private vehicles also consistently scored highly. Source: WRI

Stressed Teachers, Fearful Parents

Of the 60 teachers who participated, most were well aware of road safety problems for their students. They agreed that the issue must be addressed to improve comprehensive child growth as well as to promote sustainable mobility solutions. But capacity to enhance safety differed widely across the schools.

Teachers from the public schools had limited resources to make children’s commutes safer. The private school teachers, on the other hand, highlighted security and safety as one of their top priorities and said they were expected to design a travel management plan for each and every child to ensure door-to-door safety.

Teachers at public and private schools expressed different perspectives on road safety. Photo by Nishant Bhatnagar/WRI India

Finally, we evaluated parents’ perceptions of their children’s safety by discussing their understanding of the issues, how comfortable they were with their children on the streets and what they thought needed to change.

The parents who could afford private vehicles – largely from the private schools – preferred their children to use them due to safety concerns. The parents who could not afford or access alternatives to their children walking and cycling to school expressed feelings of helplessness. Some of the public schools do not even have school bus facilities, eliminating another option.

Parents expressed exasperation and fear over their children’s journey to school. Photo by Aashima Bhandari/WRI India

Next Steps

These engagements, supported by the FIA Foundation and done in partnership with the Municipal Corporation Gurugram and Raahgiri Foundation, are part of a series of youth-focused Vision Zero activities in the city. WRI and partners also organized a WALK Shop with students – an engaging exploration of frequent paths from a child’s perspective – that led to new commitments from the city to improve safety.

Next, the project team will use the feedback gathered to develop a pilot project that will install safer, youth-focused infrastructure around a school zone. Results from that pilot project will then help refine a better approach to school safety in Gurugram and develop a scalable school zone model.

While young people envision accessible, inclusive streets, they continue to grapple with the reality of dangerous roads that daily constrain their choices and threaten their lives. Safer streets are key to reverting the vicious circle of increasing demand for private vehicles which leads to more road crashes and air pollution but affects different populations differently, thus increasing inequality. Projects creating safe streets can help make walking and cycling viable choices, reducing congestion, promoting healthy lifestyles, improving air quality, reducing climate emissions and ultimately giving more people an opportunity to grow and thrive.

Aashima Bhandari is a Research Consultant at WRI India.

Priyanka Sulkhlan is a Manager for Cities and Transport at WRI India.