Fireworks, block parties and barbeques: Those are the first things that come to mind when the 4th of July rolls around. But what’s least talked about is the quality of breathable air on the nation’s birthday.

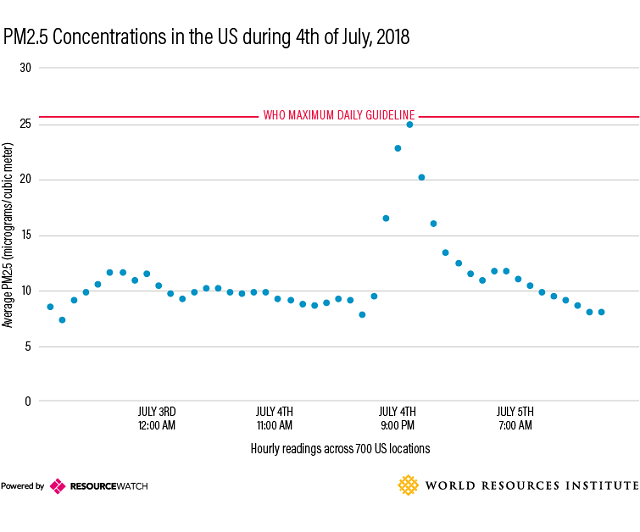

Data shows that levels of fine particulate matter (PM2.5), a pollutant linked to heart and lung disease, asthma and more, skyrocket on July 4th mainly due to fireworks. The annual average level of PM2.5 pollution in the United States is about 8 micrograms per cubic meter (μg/m3). (A microgram is one millionth of a gram.) Those pollution levels rise to 25-70 μg/m3on July 4th.

While there’s no known safe limit of PM2.5, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends keeping the 24-hour average below 25 μg/m3, and the annual average below 10 μg/m3.

A Growing Repository of Air Quality Data

CityLab originally analyzed this evident spike in air pollution levels by plotting measurements of PM2.5 using low-cost sensor data available from the PurpleAir project. PurpleAir gathers information from citizen scientists and activist groups around the country. CityLab found that PM2.5 levels shot up 70 μg/m3 on July 4, 2017.

We executed a similar analysis by gathering data from OpenAQ. The organization uses government-grade, ground monitoring station measurements in place of low-cost sensor data, aggregating information from more than 700 stations across the United States. We found the average PM2.5 levels rose to 25 μg/m3 on July 4th this year.

This difference in magnitude can be attributed to the different data sources. Low-cost sensor technology from Purple Air is hyperlocal, oftentimes placed near homes or schools. While these low-cost sensors allow citizens to learn more about air quality in individual communities, the scientific and regulatory communities question their accuracy and reliability.

Government ground-monitoring stations, on the other hand, are often strategically placed across an entire jurisdiction – and spread out to ensure coverage. Their purpose is to provide a good sense of the overall air quality conditions at the regional and city level – mainly for compliance with laws like the Clean Air Act.

Global PM2.5 concentrations in the last 24 hours. Graph by ResourceWatch

Low-cost sensors can help fill in this gap in coverage. As can be see below, the global coverage of ground monitoring stations is sparse. While OpenAQ provides free and open data to more than 5,000 monitoring stations, it’s estimated that there are approximately 15,000 stations worldwide – we just can’t see them. This is where low-cost sensor technology can come into play. Although they may be biased against (or inaccurate relative to) federal equivalent monitors, scientists agree low-cost sensors can be very useful in places with no standard measurements (like Africa, for example). Moreover, the Earth Observation teams at NASA believe that in the near future, low-cost sensor data can be integrated with ground monitoring and even satellite data to create a more comprehensive and informative observation network.

Re-thinking Fireworks as We Learn More About Air Quality

A 2017 Lancet Commission report on pollution and health named air pollution as the world’s top environmental health risk. The WHO estimates that nearly 7 million people die prematurely each year due to indoor and outdoor air pollution exposure.

The majority of this burden is carried by low- and middle-income countries. As you can see from OpenAQ data, places like India, Africa and the Middle East often have PM2.5 levels well above the WHO’s recommended limit nearly every day of the year. As fireworks become bigger and better each year, more attention and awareness should be placed on the potential consequences from poor air quality levels – otherwise the annual holiday event may one day be relabeled as the “4th of July, Independence haze.”

Learn more about air quality data in your area on ResourceWatch.

This article was originally published on ResourceWatch.

Seth Contreras is an Associate for Air Quality and Road Safety at WRI Ross Center for Sustainable Cities.

Rexon Carvalho is a Research Assistant in the Climate Program.