Several countries made climate commitments at COP26 with the goal of achieving net-zero emissions and reducing climate impacts. These goals will be impossible to achieve without making transportation sustainable, as the sector creates almost a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions. This is without considering the dangerous air pollution from traditional forms of transportation, which disproportionately harms poor and marginalized communities.

The shift from traditional vehicles with an internal combustion engine to electric vehicles will be essential to reduce emissions in the transportation sector. Although ride-hailing makes up a small fraction of vehicle miles traveled, it can play a role in the shift to sustainable, equitable transportation.

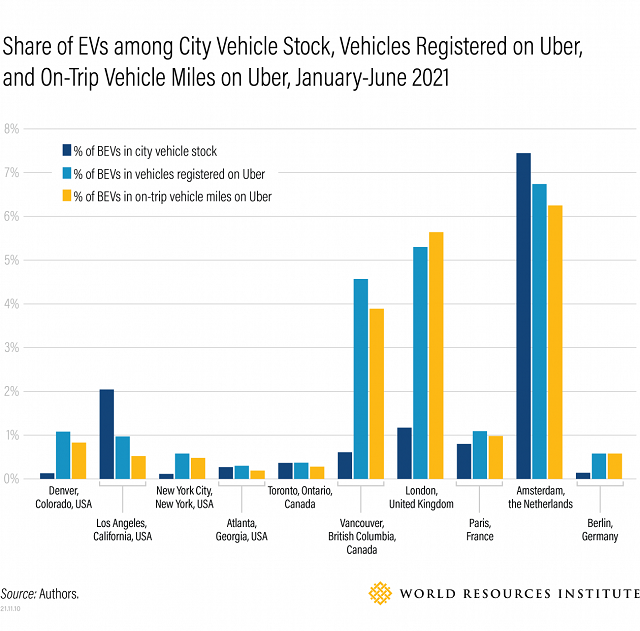

New WRI research looked at electric vehicle (EV) adoption on Uber in 10 cities in the United States, Europe and Canada and found that ride-hailing vehicles often have similar or lower rates of electrification compared to the total vehicles in the city. However, leading cities like London and Vancouver show that concerted efforts and collaboration among governments, industry and other stakeholders can address the barriers preventing ride-hailing drivers from accessing EVs. This can support the transition to sustainable transportation and help cities meet their greenhouse gas reduction targets.

Electrification in Context: Shifting From Vehicles Sold to Miles Traveled

In many countries, passenger vehicles account for a large share of their transportation emissions. In the United States, these vehicles account for over half of national transportation emissions. Since traditional vehicles emit greenhouse gases with each mile they drive, governments can increase the climate benefits of their electrification policies by focusing on more intensively used, high-mileage vehicles, such as transit, freight and ride-hailing.

Vehicles driven on ride-hailing platforms like Uber and Lyft are often high-mileage, making them a logical place to focus electrification efforts. However, many ride-hailing drivers face barriers to accessing EVs and, since the vehicles are privately owned, policies that promote the electrification of high-mileage commercial vehicles often overlook them.

In 2019, analysis of all ride-hailing companies in the United States found that only 0.3% of vehicles on these platforms were electric — half the share of EVs among private passenger vehicles overall. This is a missed opportunity to electrify vehicles that get a lot of mileage and, consequently, release more emissions. While not a complete solution on its own, high-mileage vehicles like those driven on Uber and Lyft are low-hanging fruit in the race to limit climate change.

How to Increase Ride-hailing Drivers’ Access to EVs

WRI’s research evaluated electrification policies and progress around the world to identify the largest barriers that prevent ride-hailing drivers from accessing EVs, as well as how governments, industry and other stakeholders can tackle those barriers:

1. Reduce High Up-front Costs and Increase Access to Affordable Financing

As of 2021, both the up-front cost and total cost of ownership are generally higher for EVs than for traditional vehicles — though it varies significantly by vehicle model and how intensively it is used.

Many city, state and national governments are already using grants, tax rebates and subsidies to help people access electric vehicles. However, these measures — including the U.S. federal tax credit of up to $7,500, Canada’s CAN$5,000 incentive and the United Kingdom’s £3,500 grant — often apply equally to vehicles, regardless of how much they are used. In the United States, between 2010 and 2014, an estimated 70% of the EV tax credits went to households that would have bought an EV anyway. In California, households in disadvantaged communities only accessed 6% of the rebates for battery electric vehicles. Meanwhile, ride-hailing drivers often come from the lower half of the income distribution, who typically buy fewer EVs than people with high incomes.

A lack of access to affordable financing options and credit is part of this divide. People with low incomes, low credit scores or debt may not qualify for car loans, or may only qualify for loans with high interest rates. This is part of why people of color sometimes pay thousands of dollars more than other buyers for the same vehicle. Because of this lack of access to affordable financing, lower-income households are more likely to pay for cars in cash. As a result, they need savings for the full vehicle cost, and can’t spread up-front costs over many monthly loan payments the way that many higher-income buyers can.

Governments at all levels can improve their EV incentives to overcome cost barriers. This can include targeting subsidies to high-mileage vehicles, low-income households or used vehicles, all of which would benefit ride-hailing drivers. For example, Germany’s EV subsidy is a point-of-sale benefit, rather than a tax credit. This is more equitable because low-income households may not owe enough in taxes to take full advantage of a tax credit. Ride-hailing companies themselves can also offer financial support to drivers to help cover the initial costs of EVs.

There is also potential for innovation in the models of vehicles leased, rented or shared. One example is Uber’s recent partnership with Hertz to rent Tesla EVs to ride-hailing drivers. In models like this, companies own and operate electric vehicles as a fleet, which can help spread up-front vehicle costs over time or among drivers. Fleet owners could save costs by optimizing charging, maintenance and utilization. This could increase affordability and the vehicles would eventually expand the used EV market. Additionally, this model would allow people who do not own vehicles to access ride-hailing work. Companies like Sally and Lyft’s Express Drive partnership with FlexDrive are experimenting with different approaches, but rental and lease fleets are generally overlooked by EV policies and incentives. Future research is needed on how these partnerships can be structured, and the extent to which they increase drivers’ EV access and earning potential.

2. Make EV Charging More Affordable and Convenient Through Overnight Solutions and Urban Fast-charging

Access to overnight charging is a critical way to make EV charging both convenient and affordable. Overnight charging typically offers the lowest electricity prices because vehicles can charge more slowly and at off-peak times. It is also more time-effective for most drivers, compared to charging at a public charger. However, accessing or installing a charger can be an obstacle for drivers who rent their homes or live in multiunit buildings.

Governments can increase overnight charging access by adding on-street charging in residential areas, such as Amsterdam’s demand-driven street charger installation program. They can also implement “charge by right” mandates so renters can install home chargers, such as in Vancouver and Colorado.

Some ride-hailing drivers, especially those without at-home charging or whose vehicles have short ranges, rely on public fast chargers. Therefore, it is also important to build out fast (350kW) chargers in strategic locations where ride-hailing drivers are likely to use them. Critically, these locations need fee structures that don’t undermine the economic case for ride-hailing.

Ride-hailing companies can integrate information on charging locations in their apps, like Didi did in China. This would allow drivers to easily find chargers or receive routes that bring them near chargers. Ride-hailing companies can also negotiate favorable access for ride-hailing drivers to use public charging stations, such as Uber’s partnership with bp pulse, which can help reduce the time drivers spend waiting at charging stations and decrease the revenue drivers lose from these stops.

3. Educate Drivers on EV Ownership and Benefits

Drivers are often unlikely to replace a car until an unexpected event makes their existing car unusable. This may leave them with little time to research options or wait for approvals on rebate applications. And ride-hailing drivers face an additional time crunch, as they depend on their vehicles for income.

Most members of disadvantaged communities that bought an EV were already very or exclusively interested in an EV when they started looking for their next vehicle. This means that a sustained, long-term and culturally specific approach is necessary to make sure drivers are aware of the potential benefits of EVs and can access locally specific information relevant to their purchasing decisions. Today, however, an array of disparately available financial incentives, EV models and charging options have led to a complicated landscape where drivers are often unsure whether an EV costs more or less than a traditional vehicle.

The role of raising awareness of EVs can be shared between ride-hailing companies, governments and NGOs like Veloz’s ElectricForAll campaign. For example, ride-hailing companies can create EV educational materials that are appropriate for different population groups, such as people with different primary languages or cultural backgrounds. Municipal governments can also create one-stop-shop webpages compiling all subsidies and programs available in that city, such as the Austin Energy EV Buyer’s Guide.

Realizing the Potential of Electric Ride-Hailing

Ride-hailing can be electrified in a way that promotes equity and reduces emissions, but only if a range of actors collaborate to address the unique barriers currently facing drivers currently. EV policies should be strategically designed to maximize cost-effective benefits that address intersecting environmental, economic and social challenges.

New WRI research shows that, despite promising steps, even leading cities have only just begun the transition to electric ride-hailing. Next steps for this transition include identifying the best approaches to electrifying ride-hailing platforms — many of which have not yet been widely tested — and scaling them appropriately.

Electrification is also only part of the solution to sustainable and equitable transportation. These efforts must complement compact, accessible urban planning, as well as measures that make it safe and convenient for people to walk, cycle and take public transport. The most important goal from a climate perspective is reducing the total number of passenger miles and the average CO2 emissions per passenger mile, including miles traveled on non-motorized modes and public transit. Currently, ride-hailing makes up only a small fraction of vehicle miles in most cities. Within that, electric ride-hailing’s contribution to decarbonizing transportation depends on the extent to which it replaces private vehicle miles and traditional ride-hailing miles, which is a subject of debate.

Still, electric ride-hailing can promote accelerated EV adoption down the road, as ride-hailing vehicles’ distinct charging patterns can support the development of charging infrastructure. It could also increase the adoption of EVs in low-income communities. When combined with other climate and transportation actions, electrifying ride-hailing platforms can prove a powerful asset in achieving equitable, low-emissions mobility.

This article originally appeared on WRI’s Insights.

Leah Lazer is a Research Associate with NUMO (New Urban Mobility Alliance) and the Electric School Bus Initiative at World Resources Institute.