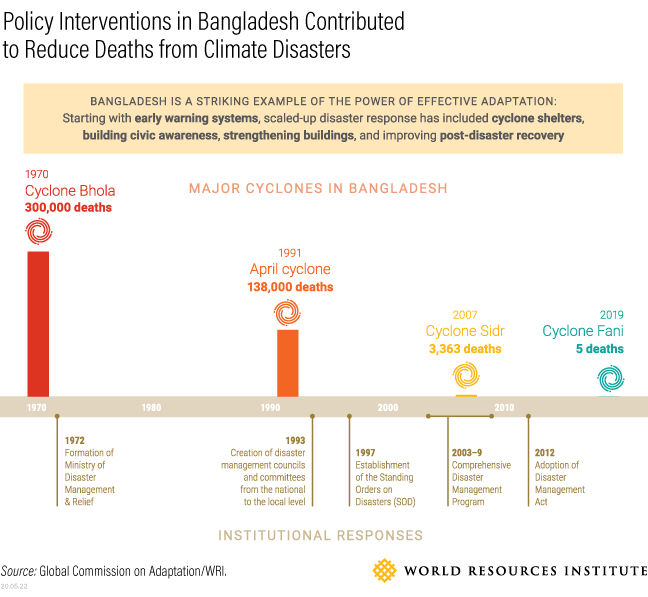

Cyclone Amphan slammed into countries surrounding the Sea of Bengal this May. The storm was the second most powerful the region has seen in two decades, affecting over 12 million people in four countries. In Bangladesh, the water surged up to 4 meters (13 feet) and 26 people died, with $130 million estimated in damages. Nevertheless, the devastation was much less severe than that caused by past cyclones.

The difference? Right before Amphan hit, Bangladeshi authorities enforced mandatory evacuation orders to move 2.4 million people into storm shelters. This response, along with making recovery funds available more rapidly after Amphan, shows that Bangladesh’s adaptation actions are saving lives.

Around the planet, people are facing stronger and more frequent storms, sea level rise and other climate change impacts. With nearly 2.4 billion people – about 40% of the world’s population – living within 100 kilometers (60 miles) of a coastline, both national and local governments must adapt to a changing climate to protect lives and economies.

Coastal protection strategies should incorporate the intensifying risks of climate change. The question is, how can decision-makers ensure that policies and plans lead to action on the ground?

Countries like Bangladesh, and cities like Cartagena in Colombia and Malabon City in the Philippines, are taking important steps toward effective climate adaptation action. New research by WRI highlights six enabling factors that can help policymakers shift from planning to implementing coastal resilience.

1. The Power of Policies

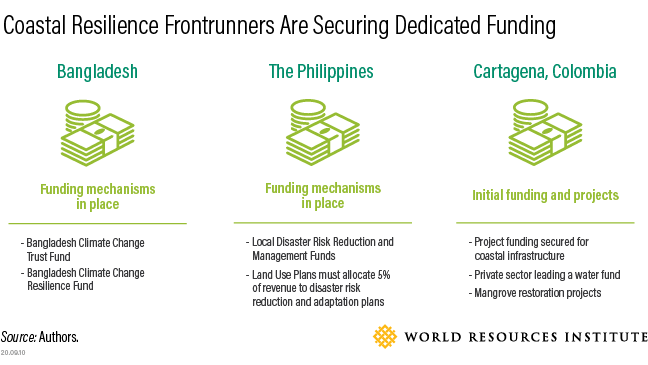

Cities and countries are better able to handle the effects of climate change when government policies specifically mandate adaptation action. The Philippine Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act of 2010 and other national policies began shifting the Philippines from merely responding to disasters to more proactively managing them. This Act links disaster preparedness explicitly to climate change adaptation and requires provinces and municipalities to develop their own disaster risk reduction and adaptation plans.

Malabon City, part of Manila’s metropolitan area, is densely populated and highly prone to flooding from rains, rivers and high tides. New national frameworks for climate adaptation incentivized Malabon City and other municipalities to incorporate disaster risk reduction and climate adaptation, using 5% of their revenue, into their urban development planning.

These national frameworks also facilitated access to funds for local preparedness and resilience programs. This has enabled Malabon City to plant trees along riverbanks and in watersheds to reduce erosion and flooding, and establish early warning systems that reach every house.

2. Sustained Leadership

A significant factor in achieving progress in Bangladesh is that politicians and government officials – including Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and the ruling party – have consistently led on adaptation issues. An All-Party Parliamentary Group on Climate Change and Disaster Risk Reduction was established in 2009. This group consists of 120 members of parliament and represents all political parties, which work together to address climate change.

Bangladesh has dramatically reduced casualties from cyclones by including climate change adaptation in coastal resilience planning to account for stronger, more frequent storms and other impacts. This includes dedicated streams of funding for on-the-ground actions to reduce disaster risks, like enhancing early warning systems and restoring approximately 195,000 hectares of severely degraded mangroves to reduce erosion and storm surges and better withstand sea-level rise.

Sustained leadership has been vital in raising awareness and making climate change adaptation an environment and development priority.

3. Smart Partnerships

Alliances keep climate adaptation on the political agenda and motivate action. Cartagena is a key Caribbean tourist and commercial hub for Colombia and Latin America. The private and financial sectors in this port city have been directly impacted by climate impacts like sea level rise, flooding and coastal erosion.

Climate change has pushed private actors, including the National Business Association of Colombia and the Cartagena Chamber of Commerce, to engage in climate adaptation as an indispensable element in fostering economic growth, stability and competitiveness. This was crucial for the creation of Plan 4C for a Competitive and Climate Compatible Cartagena, via a public, private and civil society partnership.

The plan outlines a common vision for 2040, emphasizing the importance of integrating climate risk management across Cartagena’s economic sectors and geographic territories. Strategies include a climate-resilient port, adapting vulnerable neighborhoods and rethinking the city’s inland and coastal areas. Initial funding has been secured to build 10 levees, three breakwaters and a rainwater drainage system, and the private sector is leading a successful water fund to promote good watershed practices.

In Malabon City, collaboration between the local government and the community facilitated incorporating climate adaptation into urban planning. This collaboration helped forge strong engagement by Indigenous communities, civic organizations and other groups. Their joint efforts are shaping the policies – like tree-planting and early warning systems – that aim to boost preparedness and resilience.

Both examples show how formal and informal partnerships that include diverse stakeholders are an important part of effective adaptation planning and action.

4. Accessible Information and Tools

Information on the risks, hazards and vulnerabilities caused by climate change is critical to integrating – or mainstreaming – climate adaptation into policies, plans and programs. Stakeholders being able to access and use this information was essential in Bangladesh, Cartagena and Malabon City to establishing a solid basis for policy implementation. Early benefits, including lives saved, are already apparent, as cyclone preparedness in Bangladesh illustrates.

In all three cases, research institutes or meteorological offices provided communities, the private sector and lawmakers (among other stakeholders) with credible information to understand climate risks and vulnerability. Distributing flood risk maps printed on tarpaulins for citizens in Malabon City, sharing Colombia’s Risk Atlas with the business community in Cartagena, and creating a national knowledge management program for policymakers in Bangladesh helped develop better informed, more inclusive strategies and strong partnerships, and built momentum for evidence-based coastal resilience plans and policies.

5. A Multi-level, Whole-of-government Approach

Sharing authority and responsibility across levels of government often contributes to aligning incentives to improve climate resilience. When different ministries and all levels of government (from national to local) share goals, they have greater motivation to use resources more effectively.

Bangladesh decentralizes responsibility for climate adaptation through Climate Change Cells within each ministry, and through a large network that extends from the national level to thousands of village disaster committees.

Similarly, in Colombia, the National Disaster Risk Management Unit creates a whole-of-government approach across ministries and through units established all the way to the municipal level. This approach allows different parts of government to share information about new national studies on climate risks and vulnerable locations, spurring the joint development of contingency plans for different scenarios.

In the Philippines, early warning alerts are managed by both national and local governments and disseminated to the household level. The national government calls upon local governments to identify and mitigate climate-related risks, and mandates the creation of Disaster Risk Reduction Management offices in every province, city and municipality, and of committees at the barangay (neighborhood or village) level.

6. Availability of Finance

Bangladesh, Colombia and the Philippines demonstrate that dedicated domestic funding, in combination with external financial support, is key to turning plans into action. Finance underpins all five of the other enabling factors listed above. Important progress can be made when mechanisms like funds are put into place to receive finance.

Bangladesh, for example, has established two funds, the Climate Change Trust Fund and the Bangladesh Climate Change Resilience Fund, to finance on-the-ground activities. In the last decade, the government has spent over $1.5 billion of its own resources, plus finance from external funders, on multipurpose cyclone shelters, early warning systems, mangrove restoration and more. Since 2014, the Ministry of Finance has integrated climate change into its budget planning and annual reports covering 20 government ministries.

Despite the positive examples described here, more is needed. Challenges like political instability, jurisdictional coordination and insufficient funding are still widespread. Governments and agencies at multiple levels, communities, the private sector and civil society organizations must work together to mainstream climate adaptation and disaster risk reduction better and faster when designing and implementing policies.

When these factors come together, climate adaptation works. As we saw, Cyclone Amphan was harsh, but the Bangladeshi authorities were ready. They have allocated $29-35 million so far to repair embankments, and $18 million to assist the most severely hit districts. Non-governmental organizations like BRAC and international donors have committed to help finance repairs. Ensuring that institutions can reduce climate risks and better respond when disasters hit is both possible and necessary.

The progress in Bangladesh, Cartagena and Malabon City is a model for other countries and cities working to protect lives and economies by adapting to climate change.

To learn more about how Bangladesh, Colombia and the Philippines are adapting to climate change, read the WRI working paper.

This blog was originally published on WRI’s Insights.

Stefanie Tye is a Research Associate in the Climate Resilience Practice (CRP) within WRI’s Governance Center.

Jacob Waslander is a Senior Associate at World Resources Institute.

Nadia Peimbert-Rappaport is a former Communications Advisor for WRI’s Governance Center.